Last week I blogged about a similar controversy brewing in Maine, and yesterday I blogged about the split among courts on whether students could sue pseudonymously to challenge discipline for COVID protocol violations. Today, we have yet another decision, which comes down in favor of pseudonymity as to the vaccine mandate challenge: Magistrate Judge Kathleen Tafoya’s opinion in Does v. Bd. of Regents (D. Colo.).

“Ordinarily, those using the courts must be prepared to accept the public scrutiny that is an inherent part of public trials.” Ultimately, the “test for permitting a plaintiff to proceed anonymously is whether the plaintiff has a substantial privacy right which outweighs the customary and constitutionally-embedded presumption of openness in judicial proceedings.” …

Plaintiffs first argue that medical and other privacy issues are woven throughout Plaintiffs’ claims, and that their Amended Complaint asserts claims under the Americans with Disabilities Act … requiring the Court to take special notice of Plaintiffs’ medical privacy rights. Plaintiff[s] assert[] that the vaccination status of a person is recognized to be protected, confidential information by an array of federal statutes, including the ADA itself, as well as the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, and the Health Insurance Portability and Privacy Act….

This court specifically rejects an argument that statutorily-imposed confidentiality protection, in and of itself, satisfies the highly sensitive and personal part of the anonymity argument. Nonetheless, the court will consider the statutory privacy schemes as part of making its discretionary findings here.

In this case Plaintiffs seek, first and foremost, to enforce their non-medical constitutional rights. In particular they seek a religious, not medical, exemption to the University’s policy regarding mandatory vaccination against COVID-19 and its variants. The only medical condition common to the Plaintiffs that is pertinent to the case is their unvaccinated status. It is this status which has caused all Plaintiffs to incur damages related to their employment.

Absent the current political climate, whether a person has been vaccinated or not from various maladies that might befall a human being is not particularly sensitive or personal, even though such information is protected from disclosure under HIPPA as medically related…. [S]tanding alone, a medical condition that is described as unvaccinated against COVID-19 is not so highly sensitive and personal in nature as to overcome the presumption of openness in judicial proceedings….

[H]owever, neither the court nor the litigants undertake litigation in a vacuum; the political climate and public attitudes concerning those who refuse vaccination from COVID-19 actually do exist and must be considered by the court under the balancing required by [Tenth Circuit precedent]. Plaintiffs argue that if outside persons know they have chosen to be unvaccinated, they are personally subject to a substantial risk of retaliation, including physical harm. (See Am. Compl.: online commentator stating about those attending a vaccine-mandate protest: “The anti-vaxers are ignorant trash and don’t deserve to live. Gun them down while they’re all in one place and let God sort it out”; President Biden quoted as saying “We’ve been patient, but our patience is wearing thin, and the refusal has cost all of us ….”)

Plaintiffs assert that not only are they potential targets of physical harm from others because of their unvaccinated status, they will also face harm to their professional standing from employers and educational institutions where Plaintiffs may seek employment or admission in the future, particularly in the healthcare field. Plaintiffs claim “they run the risk of ostracization, threats of harm, immediate firing, and other retaliatory consequences, if their names become known.” These anticipated damages are not currently part of those claimed in this lawsuit against the named Defendants. Therefore, in addition to considering whether potential harm to Plaintiffs by exposure of their true identities is a real threat, the court must also determine if “the injury litigated against would be incurred as a result of the disclosure of the plaintiff’s identity.” …

[T]here are no allegations that any of the plaintiffs have received any direct physical threats from anyone. Plaintiffs’ identities are currently known to the Defendants, who received each application for religious exemption from the COVID-19 vaccine mandate and were responsible for turning down the specified religious exemption requests. There is no indication that anyone associated with any defendant, knowing Plaintiffs’ identities, has threatened or harmed any plaintiff, other than as alleged in the Amended Complaint….

The harm that Plaintiffs fear if their identification is revealed comes from the public; that very same group that was invoked by President Biden in his lament that “all of us” are hurt by an individual choice to not receive a vaccination. The same public, of course, has a right to open access to judicial records and documents in civil cases.

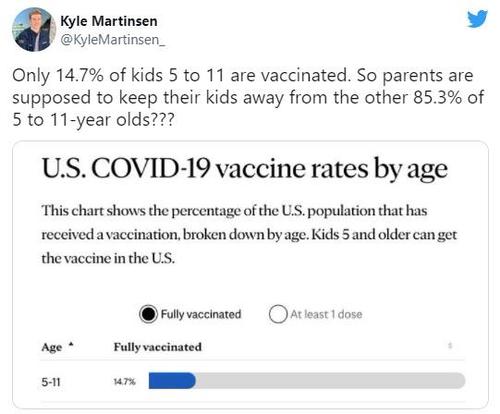

The reality at this stage of the pandemic in the United States is that vaccines are readily available to all adults in this country, free of charge, who want to be vaccinated. There is no question that there exists in our nation a certain enmity from some persons in society against those persons who choose not to become vaccinated. Plaintiffs’ Motion has presented evidence that supports their contention that choosing not to become vaccinated can stigmatize an individual as uncaring for the well-being of others, especially in light of the many mutations that have been identified thus far and the unknowns surrounding protection through vaccination if the virus is not definitively stopped from spreading. Arguments on both sides of the vaccine mandate controversy are often vitriolic and personal.

It is not this court’s place to attempt to resolve these conflicts, but simply to recognize them and balance the danger posed to individuals being labeled so-called “anti-vaxxers” against legal precedent holding that “[c]ourts are public institutions which exist for the public to serve the public interest [and] … that secret court proceedings are anathema to a free society.”

Considering the merit of this litigation, the identity of each of the Plaintiffs is of little-to- no value to the underlying allegations of the complaint. There has been no argument that the plaintiffs are not sincere in their religious objections to receiving the currently available vaccines. In fact, the individual plaintiffs who requested a religious exemption from a requirement to receive a COVID-19 vaccine are knowingly placing their own health at risk in order to uphold their religious convictions….

Further, the court agrees with Plaintiffs that there is a uniquely weak public interest in knowing the litigants’ identities in this case. The public will know that a group of people working and/or studying at the University of Colorado Anschutz medical campus have asserted religious objections to receiving the currently available COVID-19 vaccines, generally but not universally, on the basis of the use stem cells derived from aborted fetuses during research.

These exemptions were denied by the University, which only allowed religious exemptions for those individuals who are members of organized religions whose teachings entirely forbid vaccinations. Plaintiffs allege that the disallowance of their requests for religious exemption, and the ultimate penalties that were visited upon them as a result of them being unvaccinated, violated individual constitutional guarantees of religious neutrality and the entanglement between government and religion, as enshrined in the First … Amendment[] ….

The issues before the Court on the merits, therefore, do not depend on the identities of the Plaintiffs, but rather on the actions of Defendants, who are public, governmental entities and actors. The public has a very significant interest in the constitutionality of the policies of its public institutions. But, it is the policy itself and its execution at the University’s Anschutz campus that is on trial, not the individual Plaintiffs who are asserting the constitutional violations.

Therefore, … the court finds that the Plaintiffs have a substantial privacy right in protecting against public knowledge of their identities that outweighs the presumption of openness in judicial proceedings under these limited circumstances and that they should be allowed to proceed via pseudonyms until further order of the court.

The post May University Faculty/Staff/Students Sue Pseudonymously Over Limits on Religious Exemptions from COVID Vaccine Mandate? appeared first on Reason.com.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/3EUGAE9

via IFTTT