By Alex Barrow of Macro Ops Musings

Winners Evolve

This will make you sit up in your chair (emphasis mine):

In the 1990’s Harvard Business School’s Amy Edmondson performed some research to try to understand some of the qualities that make up a well-run hospital. She was not prepared, however, for one of the results her research produced. After surveying the nurses at eight different institutions, one of the things her study found was that in those hospitals where nurses reported the very best leadership team, along with great relationships with their co-workers, the number of medical errors reported was ten times higher!

What could possibly explain this outcome?

…In hospitals where the nurses felt safe and highly regarded, both by their peers and by their managers, the reason they reported more errors was that they felt more psychologically “safe.” Nurses in these more cohesive, well-led units made comments such as “mistakes are natural and normal to document,” and “mistakes are serious because of the toxicity of the drugs, so you are never afraid to tell the nurse manager.”

By contrast, in those environments where mistakes were not forgiven and miscreants were punished, nurses were more likely to report that “The environment is unforgiving, heads will roll.” In other words, it was highly likely that just as many mistakes — if not more — were made in these institutions, but not reported. Instead of learning from their mistakes, these hospitals were hiding from them.

– Don P, Peppers & Rogers Group, Does Your Company Make Enough Mistakes?

That opener is so eye-opening it is worth repeating:

“in those hospitals where nurses reported the very best leadership team, along with great relationships with their co-workers, the number of medical errors reported was ten times higher!”

Think about what this implies:

An observed reporting spread of 10-to-1 suggests the hospital error base rate is remarkably high. If there are remarkably high error rates in the confines of hospitals — where medical processes are exhaustively detailed and regimented — think how much more capacity there is for error in the relatively undocumented world of discretionary trading and investing.

And if top hospitals report an order of magnitude more errors than second or third-rate peers… while surely having a lower absolute number of errors (because top-performing institutions are better run)… think of the overwhelming number of errors sloppy performers must make… and by simple logical extension, the vast quantity of errors marginal traders and investors must be making over and over again, every single day.

(The collective presence of investor error fuels real trading opportunity, by the way, for the same reason errors at the poker table are profit opportunities for the skilled. Difference being, in a poker game you typically only have one opponent on the other side of a big hand. In a big trade you can have myriad investors, who have collectively all made the same mistake, pooling profits in your pocket by way of their positioning.)

“Heads Will Roll”

This fuels a delicious irony: If Edmondson’s findings translate to traders, one of the strongest indicators of performance quality is the frequency with which one admits and reports weaknesses or mistakes rather than hides them. This is 180 degrees from the attitude of “I never make mistakes ever.”

When interviewing a prospective money manager, then, what you want to hear is: “We’ve messed up plenty of times but learned a lot, and continue to learn.” If instead you get some variant of “We’ve always been perfect and will continue to be perfect,” walk away fast.

Why is it, then, that top performers are more willing to admit mistakes? Perhaps because lesser performers operate out of fear:

- fear that bosses will judge them harshly

- fear that clients or investors will judge harshly (or even pull funding)

- an inaccurate self-judging compass (the perception that all mistakes are bad)

- an ego-preserving data distortion field (fear of ego being bruised or even shattered)

Unfortunately, bad bosses and bad clients actually justify such fear in all too many cases. The notion that “heads will roll” is the result of subconscious signals delivered and received. Within organizations, bad leaders really do “shoot messengers”… confuse useful feedback with negative performance… fail to distinguish between luck and skill… fail to cultivate small improvements… R&D expansion into adjacent areas… better results monitoring… and so on.

In the investment world, bad clients are even worse: Rewarding slickly polished presentations from “empty suits”… chasing performance over a cliff… being emotionally averse to inevitable flat periods… disregarding the value of risk control… preferring artificial smoothness to organic robusticity… etcetera ad infinitum.

(The answer to the “heads will roll” problem is tongue-in-cheek but effective: Avoid bad bosses and clients! If someone with a functional lack of understanding and/or an obtuse point of view has the ability to impact your future in a negative way, change your situation to remove that person’s impact — or at least minimize it — as soon as you can…)

For mechanical traders, and discretionary traders who long ago check-listed their basic processes, it is also important to distinguish between “mistakes” and “weaknesses” — and to recognize that reporting and studying a “weakness” can have the same beneficial impact as a mistake.

Take the practice of honoring one’s risk points, for example, or always following a daily homework routine. For traders with a certain level of experience and professionalism, these standards are virtually never deviated from. For a seasoned and disciplined trader, mistakes defined as “a deviation from established best practices” might happen once in a quarter, or even less frequently than that (e.g. less than 2% percent of the time).

Even still though, weaknesses can be treated as a form of mistake — and every process that crosses a minimum complexity threshold – like most any trading or investing methodology — has potential weaknesses embedded that can be observed, reported on and contemplated: Flaws in the structure of the process… potential adjustments to variable component weightings… adjustments to the step-by-step pre- and post-analysis process… the shoring up of knowledge gaps or re-tooling of assumptions… and so on.

An Emphasis on Culture

At Macro Ops we are keenly aware of mistakes — and “weaknesses,” which apply even when processes are down cold — and as a result have a very strong emphasis on culture.

Institutional culture is real and powerful. You cultivate it, establish it, and strengthen it via what you do and how you do it, day after day. Think of the winning habits, processes and mindsets a successful person relies on until they are “second nature.” Then expand those mental models, ways of thinking and doing and interpreting, across a team, an organization, an entity of multiple individuals, where values and step-by-step actions, “ways of doing things” are passed on to anyone new who comes through the door. That’s culture.

As the size of our research team grows — and we are hiring in 2021 by the way! — an emphasis on growing and maintaining the MO culture becomes ever more important. This is not just because culture contributes massively to consistent outperformance (though it certainly does)… but because the quality of your culture determines the rate at which you evolve.

And the rate at which you evolve goes back to errors, weaknesses and mistakes…

Think of the following logic chain:

To approach from another angle:

The trading organizations that deliberately nurture a “culture of embracing mistakes” will receive a much higher volume of constructive feedback… and will further be better positioned to respond and hypothesize… in turn allowing them to “analyze and refine” at a faster rate… allowing them to improve and evolve at a faster rate than their peers.

In trading and investing, this is huge.

But individuals can apply these ideas too. You don’t need a team to create a culture (though it certainly helps). You can embrace mistakes on your own by asking questions like:

Cheerful vs Zero Tolerance

Keep in mind, too, that there is an important balance here. Being a winner means walking the line between tolerating mistakes — responding to them cheerfully and constructively — and ruthlessly stamping them out with a “zero tolerance” attitude.

At Macro Ops, our general mode of operation is a response of positive urgency to fresh mistakes we uncover. When the observation bell goes off, we “halt the assembly line” and ask questions like:

We can’t claim originality in this. The most successful organizations in the world, be they trading-focused or something completely different, all have some variant of the same mindset.

For instance: The following quotes are from Ray Dalio, the founder of Bridgewater (one of the most successful hedge funds of all time):

More than anything else, what differentiates people who live up to their potential from those who don’t is a willingness to look at themselves and others objectively.

I believe the biggest problem humanity faces is an ego sensitivity to finding out whether one is right or wrong and identifying what one’s strengths and weaknesses are.

Your ability to see the changing landscape and adapt is more a function of your perceptive abilities and reasoning abilities than your ability to learn and process quickly.

Recognize that you will certainly make mistakes; so will those around you and those who work for you. And what matters is how you deal with them. If you treat mistakes as learning opportunities that can yield rapid improvement if handled well, you will be excited by them.

If you don’t mind being wrong on the way to being right, you will learn a lot.

Of course, there is also a certain class of mistakes we have “zero tolerance” for — things like:

In other words, some mistakes are understandable and even exciting — as Ray Dalio puts it — because their presence indicates forward evolution and opportunity for advancement on the capability frontier.

But other mistakes — the ones that go back to well-covered areas, well-developed process, or issues of moral code and doing one’s best work — represent serious internal issues and thus receive a brutally harsh response. (We aren’t afraid to lose our tempers.)

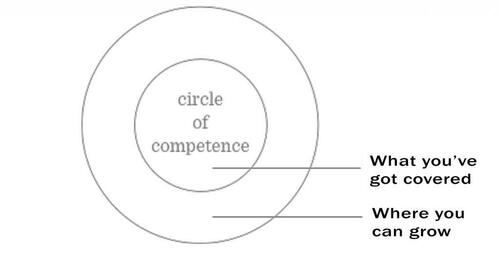

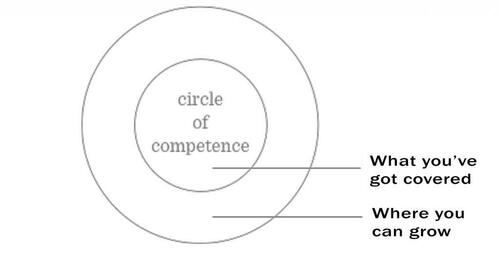

The Circle of Competence

In evaluating mistakes, you can picture acceptable vs unacceptable in the context of a circle — a “circle of competence.”

Mistakes on the circumference of the growth circle are acceptable, and even desirable… if they represent intelligent efforts at expanding competence. The only way you make the circle bigger is by evolving your capabilities… and you do this via thoughtful trial and error, risk-adjusted tinkering and refining, allocations to R&D, and so on.

Mistakes deep within the circle are unacceptable, however, because they represent failure in areas already covered… or failure in areas that should be covered… or worse yet, a failure of internal structure as relating to things like capacity for hard work, commitment to accuracy, moral commitment to excellence, and so on.

Furthermore there are at least two competence circles that matter: The circle for the individual team member, and the circle for the organization as a whole. Efforts to expand the organization as a whole — via contributions to team knowledge or net capability — are appreciated and rewarded. There are many “good failures” in respect to this endeavor, because the potential ROI (return on investment) is so long-term beneficial. (This is a good acid test of leadership by the way. Does the leadership “get” this? Do they embrace it as a directive?)

On the individual team member side, competence circles should match up with experience levels and expectations. A senior trader or analyst with 10+ years of experience will be expected to have a much larger competence circle than, say, a fresh analyst with lots of talent but only a modicum of seasoning. For this reason a certain type of mistake or weakness may be acceptable in one team member but not in another, again relative to situational differences.

Altogether this unites to create an enlightened (in our opinion) and goal-oriented approach to evaluating mistakes and weaknesses: We want to maximize top performance, minimize “unforced errors” and low-grade process failures, and cultivate a healthy expansion of competence for both individual team members and the organization as a whole. Mistakes made in alignment with this goal are not only tolerated but appreciated — “winners evolve” is our short and sweet motto, and it applies across the board. Mistakes of the unacceptable kind, if made too frequently, result in a friendly parting of the ways (so as to avoid team resentment and “Full Metal Jacket” treatment).

Confidently Humble

In many ways, being a successful trader is a paradox. You must develop a deep sense of confidence in your methodology and talent, yet remain ever humble and flexible. You have to trust yourself, but also know when to intelligently doubt yourself — and have no fear of doing so. You need a profound unshakeable faith in who you are and what you can do… yet at the same time maintaining the attitude of the humble student, the raw beginner, the white belt always ready to learn.

Getting this mix right is also the key to personal evolution and incremental improvement, because evolution itself is such an iterative, trial-and-error driven process (and thus a reflective / contemplative process). It’s not enough to get your hands dirty and fall on your face every so often. Having fallen, you must have the presence of mind to put your ego aside… objectively examine your weakness or mistake… and then put in the elbow grease of analyzing, and intelligently responding to, the data born of your stumble.

None of this is rocket science. But it is harder than it sounds… harder even than rocket science in some aspects… and thus represents a golden opportunity, because so few can do it! The need for ego preservation is a massive block to trading in so many ways — even among people who appear “humble” on the outside, yet cannot apply a “culture of embracing mistakes” on the internal level.