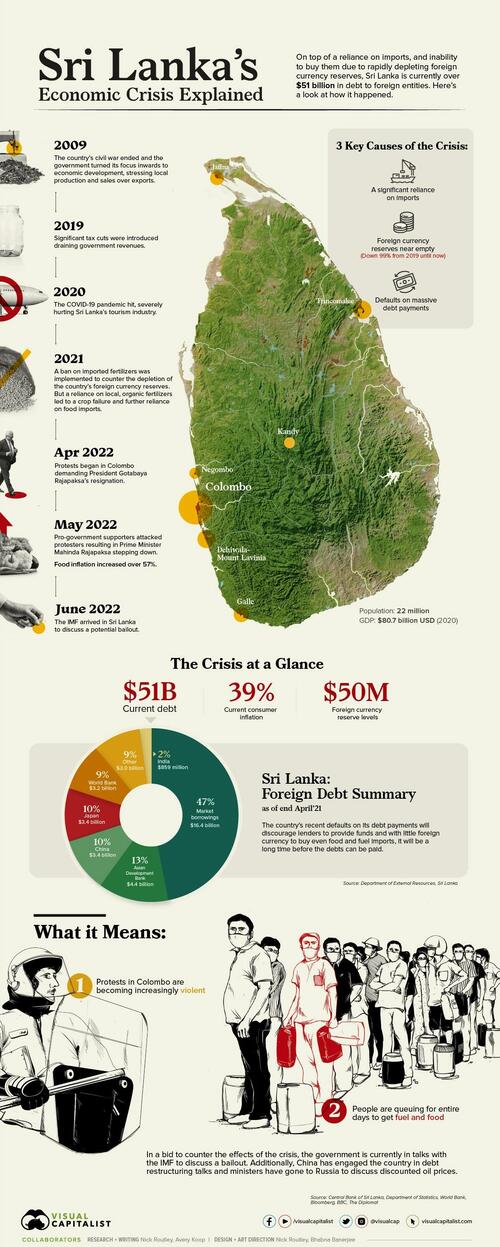

Understanding The Economic Crisis In Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka is currently in an economic and political crisis of mass proportions, recently culminating in a default on its debt payments. The country is also nearly at empty on their foreign currency reserves, decreasing the ability to purchase imports and driving up domestic prices for goods.

As Visual Capitalist’s Avery Koop details below, there are several reasons for this crisis and the economic turmoil has sparked mass protests and violence across the country. This visual breaks down some of the elements that led to Sri Lanka’s current situation.

A Timeline of Events

The ongoing problems in Sri Lanka have bubbled up after years of economic mismanagement. Here’s a brief timeline looking at just some of the recent factors.

2009

In 2009, a decades-long civil war in the country ended and the government’s focus turned inward towards domestic production. However, a stress on local production and sales, instead of exports, increased the reliance on foreign goods.

2019

Unprompted cuts were introduced on income tax in 2019, leading to significant losses in government revenue, draining an already cash-strapped country.

2020

The COVID-19 pandemic hit the world causing border closures globally and stifling one of Sri Lanka’s most lucrative industries. Prior to the pandemic, in 2018, tourism contributed nearly 5% of the country’s GDP and generated over 388,000 jobs. In 2020, tourism’s share of GDP had dropped to 0.8%, with over 40,000 jobs lost to that point.

2021

Recently, the Sri Lankan government introduced a ban on foreign-made chemical fertilizers. The ban was meant to counter the depletion of the country’s foreign currency reserves.

However, with only local, organic fertilizers available to farmers, a massive crop failure occurred and Sri Lankans were subsequently forced to rely even more heavily on imports, further depleting reserves.

April 2022

In early April this year, massive protests calling for President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s resignation, sparked in Sri Lanka’s capital city, Colombo.

May 2022

In May, pro-government supporters brutally attacked protesters. Subsequently, Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa, brother of President Rajapaksa, stepped down and was replaced with former PM, Ranil Wickremesinghe.

June 2022

Recently, the government approved a four-day work week to allow citizens an extra day to grow food, as prices continue to shoot up. Food inflation increased over 57% in May.

Additionally, the increasing prices on grain caused by the war in Ukraine and rising fuel prices globally have played into an already dire situation in Sri Lanka.

The Key Information

“Our economy has completely collapsed.”

– PRIME MINISTER RANIL WICKREMESINGHE TO PARLIAMENT LAST WEEK.

One of the main causes of the economic crisis in Sri Lanka is the reliance on imports and the amount spent on them. Let’s take a look at the numbers:

-

2021 total imports = $20.6 billion USD

-

2022 total imports (to March) = $5.7 billion USD

In contrast, the most recent reported foreign currency reserve levels in the country were at an abysmal $50 million, having plummeted an astounding 99%, from $7.6 billion in 2019.

Some of the top imports in 2021, according to the country’s central bank were:

-

Refined petroleum = $2.8 billion

-

Textiles = $3.1 billion

-

Chemical products = $1.1 billion

-

Food & beverage = $1.7 billion

Of course, without the cash to purchase these goods from abroad, Sri Lankans face an increasingly drastic situation.

Additionally, the debt Sri Lanka has incurred is huge, further hampering their ability to boost their reserves. Recently, they defaulted on a $78 million loan from international creditors, and in total, they’ve borrowed $50.7 billion.

The largest source of their debt is by far due to market borrowings, followed closely by loans taken from the Asian Development Bank, China, and Japan, among others.

What it Means

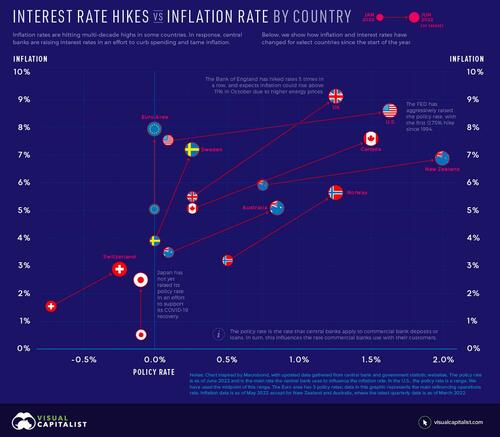

Sri Lanka is home to more than 22 million people who are rapidly losing the ability to purchase everyday goods. Consumer inflation reached 39% at the end of May.

Due to power outages meant to save energy and fuel, schools are currently shuttered and children have nowhere to go during the day. Protesters calling for the president’s resignation have been camped in the capital for months, facing tear gas from police and backlash from president Rajapaksa’s supporters, but many have also responded violently to pushback.

India and China have agreed to send help to the country and the the International Monetary Fund recently arrived in the country to discuss a bailout. Additionally, the government has sent ministers to Russia to discuss a deal for discounted oil imports.

A Foreshadowing for Low Income Countries

Governments need foreign currency in order to purchase goods from abroad. Without the ability to purchase or borrow foreign currency, the Sri Lankan government cannot buy desperately needed imports, including food staples and fuel, causing domestic prices to rise.

Furthermore, defaults on loan payments discourage foreign direct investment and devalue the national currency, making future borrowing more difficult.

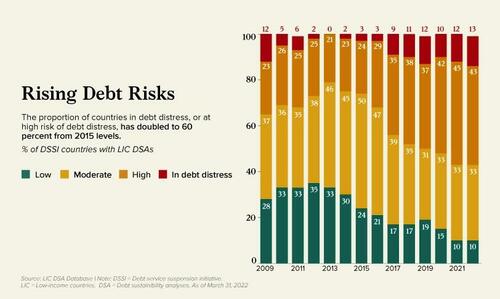

What’s happening in Sri Lanka may be an ominous preview of what’s to come in other low and middle-income countries, as the risk of debt distress continues to rise globally.

The Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) was implemented by G20 countries, suspending nearly $13 billion in debt from the start of the pandemic until late 2021.

Some DSSI and LIC countries facing a high risk of debt distress include Zambia, Ethiopia, and Tajikistan, to name a few.

Going forward, Sri Lanka’s next steps in managing this situation will either serve as a useful exam for other countries at risk or a warning worth heeding.

Tyler Durden

Sun, 07/03/2022 – 19:05

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/k5K7Xow Tyler Durden