Authored by Charlie Tidmarsh via RealClear Wire,

It’s been nearly six months since the first installment of the Twitter Files—the journalistic effort by Matt Taibbi, Michael Shellenberger, Bari Weiss, Lee Fang, and many others to expose the myriad channels by which the U.S government cooperated with Twitter on content moderation and censorship—was first published. Twitter Files One, perhaps the mildest of more than 20 unique reports, details the social media company’s internal deliberations in the days before the New York Post’s story about Hunter Biden’s laptop was removed from the site. Later reports have exposed the tendrils of a governmental apparatus that influenced some of the most significant media distortions in recent American history, from the fraudulent Hamilton 68 misinformation tracking dashboard to the FBI’s intimate involvement with Twitter’s content-moderation practices.

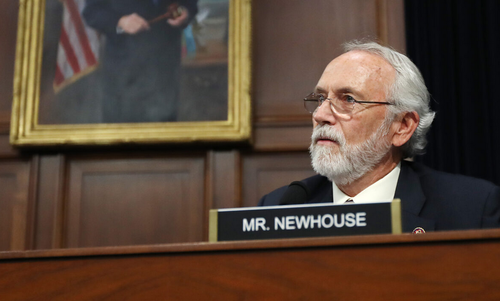

For six months, not much of consequence has happened, either in Washington or the mainstream media, in response. Those who owe us mea culpas have not provided them, tending instead to attack the individual reporters or ignore their findings. Meanwhile, some concerning developments have emerged: Congress formed the Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government in order to conduct its own investigation, which would have been encouraging had it not culminated in representative Stacey Plaskett of the U.S. Virgin Islands threatening Taibbi with imprisonment for his testimony; Mark Warner’s RESTRICT Act, which would yield the federal government an enormous media-censorship leeway, was introduced in the Senate in March; Montana banned TikTok statewide; special counsel John Durham’s report on Russian interference was released and received with a profound lack of interest in the FBI’s dubious and error-laden investigation; and the Global Disinformation Index, a British NGO that ranks news outlets on a scale of “risky” to “least risky” (this website is one of the GDI’s ten “riskiest”), was shown to have received funding from the State Department (via the National Endowment for Democracy), which it subsequently lost.

As shocking and foreboding as these anti-democratic actions are, not many commentators are treating them as interconnected expressions of a single censorship apparatus. Michael Shellenberger and his colleagues Alex Gutentag and Matt Taibbi are now undertaking a monumental attempt at defining that apparatus: they call it the Censorship Industrial Complex. Shellenberger and Gutentag are two of the few journalists who not only take the reality of increased government censorship efforts seriously but also consider it a systemic, unified, and global threat, as opposed to a few discreet but regrettable extensions of U.S. political power.

The complex is founded on euphemistic, Astro-turfed neologisms—“misinformation,” “disinformation,” “infodemic,” and, absurdly, “malinformation,” which is defined by The Cybersecurity & Infrastructure Security Agency as information “which is based on fact, but used out of context to mislead, harm, or manipulate” (my emphasis)—and prosecuted by a coterie of journalists, academics, NGOs and nonprofits who claim neutral expertise in adjudicating what is true and what is false. World governments have eerily aligned their definitions of these terms and then cooperated with non-state actors to censor online speech in accordance, all with the stated and ostensibly noble aim of “reducing harm.”

Their reporting, which takes place almost exclusively on Substack and Twitter (Gutentag is also a columnist at Tablet), has called attention to the ways in which major democratic governments in Europe, Canada, the UK, and Ireland are replicating the American tactic: define certain types of speech as harmful and then empower a bureaucratic network of think tanks, research agencies, and nonprofits to enforce strict Internet censorship practices that ensure that so-called harmful speech is repressed.

The most thorough history of how this bureaucracy came into power was provided by Jacob Siegel, a former U.S Army intelligence officer in both Iraq and Afghanistan, writing in Tablet. Strikingly, Siegel compares the emergence of this new complex to its closest analog in American history: McCarthyism. And he locates its legislative origin on December 23, 2016, the date that Barack Obama signed into law the Countering Foreign Propaganda and Disinformation Act. What began as a campaign against foreign information warfare morphed into a domestic censorship apparatus in the aftermath of Donald Trump taking office. In this way, it echoes the Military Industrial Complex by leveraging wartime expansions of government authority towards domestic goals. While the primary agents are certain federal intelligence and security agencies and their cooperating NGOs1, Siegel sees the media as playing a remarkably complicit role in the last seven years. “The American press, he writes, “once the guardian of democracy, was hollowed out to the point that it could be worn like a hand puppet by the U.S security agencies and party operatives.”

Shellenberger and Gutentag have provided the first invaluable step in a massive project: they’ve defined the problem. “The Twitter Files gave us a window,” Shellenberger writes, “into how government agencies, civil society, and tech companies work together to censor social media users. Now, key nations are attempting to enshrine this coordination into law explicitly.”

In November 2022, the E.U. passed the Digital Services Act, which legally compels large online media platforms to remove hate speech and disinformation from their platforms under threat of fines as large as six percent of annual global revenue. If passed in the U.S., RESTRICT, with its loopholes and vague jargon, threatens to give the federal government unprecedented ability to spy on the online activity of its citizens. The Criminal Justice (Incitement to Violence or Hatred and Hate Offences) Bill 2022, which passed the lower house of the Irish Parliament, could soon render the possession of “hateful” digital material illegal in that country. Canadian Bill C-11 has passed in the Senate, amending the former Broadcasting Act to allow the government to filter and promote streamed media. Brazil’s proposed Bill 2630, the so-called Fake News Law, will compel social media platforms to regulate “fake news” and misinformation on their platforms more strictly or face severe fines. An early draft of this bill included a provision that would allow the imprisonment for up to five years of anyone spreading content that “threatened social peace and economic order.”

According to Shellenberger, Gutentag, and their colleagues at the Substack Public, what tends to unify these efforts is a reliance on identical, porous definitions of what counts as bad or hateful information, as well as an emphasis on words such as “safety,” “harm reduction,” and “protection.” This is precisely what makes the Censorship Industrial Complex so insidious. No one wants truly false information to dominate our important discussion spaces, or genuine hate to crowd out constructive public discourse. But the verbiage these governments operate with grants tremendous leeway in how such speech is defined and censored. This slippage has already played out in the case of Hunter Biden’s laptop, the contents of which were almost immediately deemed “disinformation” as a justification for Twitter to remove the story from its platform in the run-up to the 2020 presidential election; we now know the material was not only legitimate but in the FBI’s possession in December of 2019.

Shellenberger and Gutentag are calling on any whistleblowers, journalists, or individuals with first-hand experience with this censorship regime to contact them immediately. The first official meeting of this growing anti-censorship movement will be held in London next month. Anyone with information or experience to share is encouraged to reach out on their website, censorshipindustrialcomplex.org, and support Public’s reporting on Substack.