Authored by Fred Fleitz via American Greatness,

Editor’s note: this article is an update of a lecture the author recently gave to a Council for National Policy conference.

Good morning. Today, I am going to talk about a difficult and controversial topic that is dividing the American people and the conservative movement: what American policy should be concerning the war in Ukraine.

This is a difficult topic to discuss because if you say the wrong thing about this conflict – if you stray from the approved Washington establishment/mainstream media narrative – you are immediately accused of being pro-Russia or pro-Putin or anti-Ukraine.

We saw this in May during a CNN town hall when President Donald Trump was asked whether he wanted Ukraine to win this conflict, and Trump said, “I want everybody to stop dying. They’re dying. Russians and Ukrainians. I want them to stop dying.” Trump added, “I don’t think in terms of winning and losing; I think in terms of getting it settled so we can stop killing all those people.”

When the former president was asked if he thinks Putin is a war criminal, he replied, “This should be discussed later, and if you say he’s a war criminal, it’s going to be a lot harder to make a deal later to get this thing stopped.”

This was followed by the usual attacks on President Trump by Democrats and the press, accusing him of favoring Putin and ignoring the plight of the Ukrainian people.

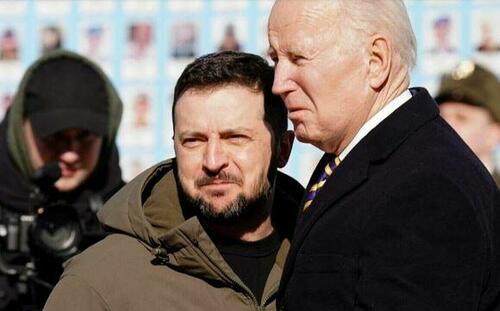

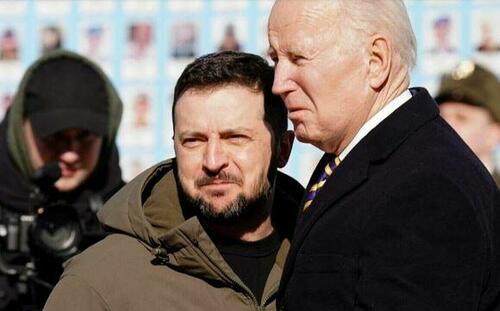

By contrast, Joe Biden has called Putin a killer and a war criminal. Biden also has stated his support for an International Criminal Court warrant to arrest Putin.

So who is being more presidential here? The reality is that unless the U.S. is willing to risk nuclear war to depose Putin and remove him from office, President Trump is right that we need to find a way to work with him. The U.S. needs to find a way to live with Putin. This is not an ideal situation, but we have lived with the leaders of adversary states throughout the history of our country.

I also agree with Trump that the focus of American policy for Ukraine should be a cease-fire and starting peace talks. Talking about this does not mean you’re siding with Russia or Putin. It means you are putting the interests and security of our country first.

I want to discuss where we are in this conflict before I talk about what U.S. policy should be.

Although Ukraine racked up political and military support from the United States and Europe in the run-up to its current counteroffensive, this campaign has fallen well short of its goal of reclaiming large amounts of Ukrainian territory because Russia had plenty of time to prepare for the offensive by laying mines, creating tank traps and digging in their troops. Russia also has the advantage of air power.

Ukrainian leaders claim the counteroffensive’s success has been limited because they have not received the arms they need from the West and lack air power. Ukraine also is running out of 155mm artillery shells. Although the U.S. agreed last spring to send F-16s to Ukraine, they won’t appear on the battlefield before early next year.

To bolster the counteroffensive, the Biden Administration agreed last month to provide Ukraine with cluster munitions – artillery shells that explode in the air and release dozens to hundreds of smaller bomblets across a wide expanse of land as large as a football field. This was a controversial decision because these weapons are banned in 123 countries under the 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions. The UK, Germany, France, and Canada are parties to the accord and have objected to the U.S. providing Ukraine with these weapons.

There are other troubling developments in this war.

In addition to the spring offensive, Ukraine has begun to attack targets in Crimea which Russia seized in 2014 and could launch a campaign to retake this territory. As part of this effort, Ukraine launched a drone attack on July 17 against the Kerch Bridge, which links Russia to Crimea, killing two civilians. Russia retaliated by withdrawing from a UN-brokered agreement allowing Ukraine to export grain through the Black Sea and began a massive missile and drone attack against Odesa, the main port that Ukraine uses to ship millions of tons of grain to the world.

There also are reports that Ukraine may be planning to occupy Russian villages to gain leverage over Moscow; bombing a pipeline that transfers Russian oil to Hungary; and possibly firing long-range missiles deep inside Russia to try to pressure the Russians to come to a peace agreement.

We’ve heard claims over the past year that this conflict has become a proxy U.S. war against Russia and that if we push Russia too far, we could approach a red line where Russia decides to use nuclear weapons. I don’t know where that red line is, but I believe these reports, if they are accurate, are getting pretty close to this red line.

In a famous 1879 speech, General William T. Sherman said, “war is hell” and lamented the horrors of war, including cities and homes in ashes and thousands of men lying on the ground, their dead faces looking up at the skies. I could accept continuing to support the hell of the war in Ukraine despite its high human cost, Ukraine using cluster munitions, and the threat to American security if I thought the Ukrainian military had any chance of expelling the Russians and establishing a lasting peace.

But that’s not in the cards. Foreign policy experts increasingly believe this conflict will likely be a long and inconclusive war of attrition. Richard Haass, president of the Council on Foreign Relations, said in an April 2023 article, “the most likely outcome of the conflict is not a complete Ukrainian victory but a bloody stalemate.”

It’s not getting much coverage, but this also is the position of European leaders, who have privately told Ukrainian President Zelensky that they expect him to start peace talks. They’ve told him that they do not expect Ukraine will take back most of the territory Russia has seized. They have informed Zelensky that large amounts of military aid to Ukraine from their countries will not continue indefinitely because their people do not want to support and arm an endless war in Ukraine.

Many in the United States on the right and the left share this view.

Zelensky and the Ukrainian people obviously don’t see it that way. They want their country back. You have to admire the determination and skill of the Ukrainian army and how they bravely fought back against a much larger and more powerful foe. They want everything back, including Crimea. The Biden Administration has been supportive of this and has been hostile to peace talks and a cease-fire. Biden officials continue to argue that any peace settlement before a “complete” Ukrainian victory would reward Putin’s aggression.

Biden’s strategy for Ukraine is to provide military aid “for as long as it takes.” This is not a viable strategy.

Americans are a compassionate people and want Ukraine to win this war. We would like to see Russian forces expelled. We want to help. We want to do the right thing.

But Ukraine is not a vital U.S. interest. Therefore, our involvement in this conflict must be limited and not open-ended. We know from experience that America is not the world’s policeman. We have our own problems at home. We’re using up our weapon arsenals, especially advanced missiles, that we may need elsewhere, such as if China attacks Taiwan. Although it is good news that Germany, the U.K. and France are providing additional weapons to Ukraine, they are still far from doing their share in providing military aid to Ukraine. The U.S. still carries the lion’s share of providing this aid.

Ukrainian officials and some of their Western supporters argue that we must stop Russia in Ukraine because after Putin wins this war, he will invade Eastern Europe. This is nonsense. Putin has never shown interest in invading Eastern Europe after Ukraine. If you read his writings, Putin’s invasion of Ukraine was because of his perverse reading of history: Ukraine is not a separate country and Ukrainians are not a separate people.

Even if it was the original intention of Putin to invade Eastern Europe after he conquered Ukraine, this is no longer feasible because his army has been devastated. It isn’t going to invade Poland after a Russian victory or peace settlement in Ukraine.

Sadly, if the Biden Administration had understood Putin’s writings on Ukraine, maybe this invasion wouldn’t have occurred. Although I believe the main factor that caused Putin to invade Ukraine was his perception of U.S. weakness under President Biden, I also think it’s very likely that Biden goaded the Russians into invading by holding out the prospect of NATO membership when he didn’t have to.

President Biden repeated this mistake at the recent NATO summit in Lithuania when he assured Ukraine that it will join NATO after the war ends. Because of Putin’s adamant opposition to Ukraine joining NATO, this promise probably will discourage him from agreeing to peace talks or a cease-fire.

Even more worrisome, if a settlement could be agreed, Putin likely will invade Ukraine again if it is a NATO member. Washington would then be required under Article 5 of the North Atlantic Treaty to use U.S. military power to defend Ukraine, possibly including sending U.S. troops to engage Russian troops.

We would then be faced with the real possibility of World War III.

This is why I believe Trump had it right when he said the U.S. must prioritize ending the war now.

And then there’s Chinese President Xi Jinping, who is trying to wriggle out a role for himself in this conflict by playing the peacemaker. Xi’s intention is to find an outcome that is beneficial to China and Russia at America’s expense. This is not in our interest.

So what should the U.S. do? President Biden should begin to lead in this conflict with his own peace plan. American officials must start being tough with Zelensky and be clear that we’re not going to continue our current level of military support indefinitely. The U.S. also must tell Zelensky that it will not tolerate Ukraine expanding the war with a campaign to retake Crimea or doing other things that would risk a nuclear confrontation with Russia.

President Biden also must retract his offer of NATO membership for Ukraine and instead state that this is off the table for an extended period, maybe 25 years. Instead, Ukraine would be provided with the weapons it needs to defend itself over the long term to prevent Russia from exploiting a pause in the fighting to rearm and resume the war.

Ukraine would not give up its demands to reclaim its territory, but would agree to negotiations to resolve these demands with the understanding that they probably will not be resolved until some future date when Putin is out of power.

Getting Putin to negotiate in good faith and honor an agreement will be difficult. Richard Haass has proposed shoring up a cease-fire agreement to assure Russian cooperation by creating a demilitarized zone and deploying peacekeepers to verify compliance with a cease-fire. This has worked for decades in “frozen conflicts” in Cyprus and Korea and may be the best option for a lasting peace between Russia and Ukraine.

The U.S. and its NATO allies could start peace talks right now with empty chairs for the Russians and the Ukrainians. We should start discussions immediately with European states about confidence-building measures and how to rebuild Ukraine. Ukraine and Russia could join these talks when they’re ready.

A settlement will not be perfect. It will likely be a fragile cease-fire for a frozen conflict. Ukraine is not going to get most of its territory back. Borders will be where each side’s troops end up. There won’t be war crimes trials, and President Biden should stop saying there will be. Hopefully, there will be some agreement for reparations from Russia, perhaps a levy on Russian oil sales.

The Ukrainian government and the Ukrainian people will have trouble accepting this. Their supporters will also. But as Donald Trump said at the CNN town hall last May, “I want everyone to stop dying.” That’s my view, too.

Fred Fleitz is vice-chair of the America First Policy Institute Center for American Security. He previously served as National Security Council chief of staff, CIA analyst, and a House Intelligence Committee staff member.

UK-

UK- US-

US- EU sponsorship of Al Qaeda & ISIS, today as the BRICS/SCO nations look to investing in

EU sponsorship of Al Qaeda & ISIS, today as the BRICS/SCO nations look to investing in

(@DeborahMeaden)

(@DeborahMeaden)