As we showed very vividly yesterday, while the world is comfortably distracted with mundane questions of whether the Fed will taper this, the BOJ will untaper that, or if the ECB will finally rebel against an “oppressive” German regime where math and logic still matter, the real story – with $3.5 trillion in asset (and debt) creation per year, is China. China, however, is increasingly aware that in the grand scheme of things, its credit spigot is the marginal driver of global liquidity, which is great of the rest of the world, but with an epic accumulation of bad debt and NPLs, all the downside is left for China while the upside is shared with the world, and especially the NY, London, and SF housing markets. Which is why it was not surprising to learn that China has drafted rules banning banks from evading lending limits by structuring loans to other financial institutions so that they can be recorded as asset sales, Bloomberg reports.

Specifically, China appears to be targeting that little-discussed elsewhere component of finance, shadow banking. Per Bloomberg, the regulations drawn up by the China Banking Regulatory Commission impose restrictions on lenders’ interbank business by banning borrowers from using resale or repurchase agreements to move assets off their balance sheets. Banks would also be required to take provisions on such assets while the transactions are in effect. Ironically, it may be that soon China will be more advanced in recognizing the various exposures of shadow banking than the US, which is still wallowing under FAS 140 which allows banks to book a repo as both an asset and a liability.

Recall from a Matt King footnote in his seminal “Are the Brokers Broken?”

Quite apart from the fact that FAS 140 contradicts itself (with paragraph 15 (d) making borrowed versus pledged transactions off balance sheet, and paragraph 94 making them on balance sheet, a topic complained about by many broker-dealers immediately after its issue), there seems to be little consensus as to who is the borrower and who is the lender. As far as we can tell, terms like ‘borrower’ and ‘lender’ are used in exactly the opposite sense in the accounting regulations relative to standard market practice. The description above follows common market practice. The accounting documents seem to refer to this the other way around, a source of confusion commented upon in some of the accounting literature

So while in the US one may be a borrower or a lender at the same time courtesy of lax regulatory shadow banking definition (depending on how much the FASB has been bribed by the highest bidder), in China things will very soon become far more distinct:

The rules would add to measures this year tightening oversight of lending, such as limits on investments by wealth management products and an audit of local government debt, on concerns that bad loans will mount. The deputy head of the Communist Party’s main finance and economic policy body warned last week that one or two small banks may fail next year because of their reliance on short-term interbank borrowing.

“China’s banks and regulators are playing this cat-and-mouse game in which the banks constantly come up with new gimmicks to bypass regulations,” Wendy Tang, a Shanghai-based analyst at Northeast Securities Co., said by phone. “The CBRC has no choice but to impose bans on their interbank business, which in recent years has become a high-leverage financing tool and may at some point threaten financial stability.”

Cutting all the fluff aside, what China is doing is effectively cracking down on the the wild and unchecked repo market, and specifically re-re-rehypothecation, which allows one bank to reuse the same ‘asset’ countless times, and allow it to appear in numerous balance sheets.

The proposed rules target a practice where one bank buys an asset from another and sells it back at a higher price after an agreed period.

The reason why China is suddenly concerned about shadow banking is that it has exploded as a source of funding in recent years:

Mid-sized Chinese banks got 23 percent of their funding and capital from the interbank market at the end of 2012, compared with 9 percent for the largest state-owned banks, Moody’s Investors Service said in June. The ratings company forecast a further increase in non-performing loans as weaker borrowers find it hard to refinance.

And while we are confident Chinese financial geniuses will find ways to bypass this attempt to curb breakneck credit expansion in due course, in the meantime, Chinese liquidity conditions are certain to get far tighter.

This is precisely the WSJ reported overnight, when it observed that yields on Chinese government debt have soared to their highest levels in nearly nine years amid Beijing’s relentless drive to tighten the monetary spigots in the world’s second-largest economy. “The higher yields on government debt have pushed up borrowing costs broadly, creating obstacles for companies and government agencies looking to tap bond markets. Several Chinese development banks, which have mandates to encourage growth through targeted investments, have had to either scale back borrowing plans or postpone bond sales.”

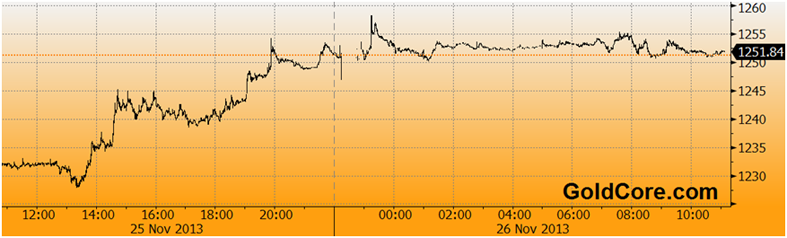

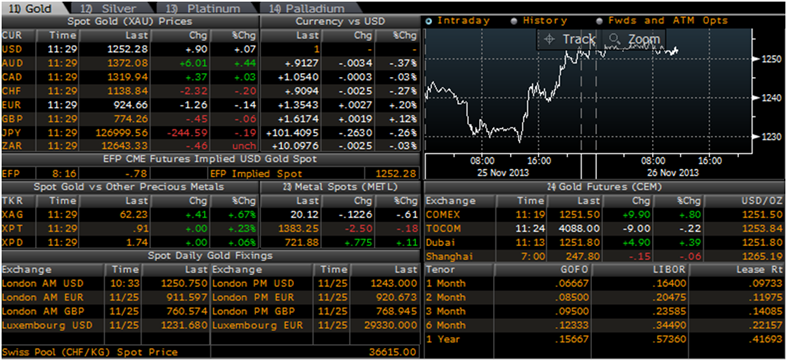

This should not come as a surprise in the aftermath of the recent spotlight on China’s biggest tabboo topic of all: the soaring bad debt, which is the weakest link in the entire, $25 trillion Chinese financial system (by bank assets). So while the Fed endlessly dithers about whether to taper, or not to taper, China is very quietly moving to do just that. Only the market has finally noticed:

The slowing pace of bond sales from earlier in the year is reviving worries of reduced credit and soaring funding costs that were sparked in June, when China’s debt markets were rattled by a cash crunch.

The rise in borrowing costs and shrinking access to credit could undercut the recent uptick in China’s economy that global investors in stock, commodity and currency markets have cheered. Wobbly growth in China could undermine economic recovery in the rest of the world.

“If borrowing costs don’t fall in time, whether the real economy could bear the burden is a big question,” said Wendy Chen, an economist at Nomura Securities.

Chinese bond yields are rising amid a lack of demand among the big banks, pension funds and other institutional money managers, analysts say. These investors, traditionally the heavyweights in China’s bond market, have seen their funding costs rise in tandem with interbank lending rates, which are controlled by China’s central bank. The country’s bond market is largely closed to foreign investors.

The yield on China’s benchmark 10-year government bond was at 4.65% Monday, down from 4.71% Friday. Last Wednesday’s 4.72% was the highest since January 2005, according to data providers WIND Info and Thomson Reuters. The record is 4.88% set in November 2004. Bond yields and prices move in opposite directions.

“The recent sharp rise in bond yields was mostly due to worsening funding conditions and growing expectations for a tighter monetary policy as Beijing seeks to deleverage the economy,” said Duan Jihua, deputy general manager at Guohai Securities.

As government-bond yields have risen, the average yield on debt issued by China’s highest-rated companies rose to 6.21% as of Friday—the highest since 2006, when WIND Info began compiling the data.

In conclusion, it goes without saying that should China suddenly be hit with the double whammy of regulatory tightening in both shadow and traditional funding liquidity conduits, that things for the world’s biggest and fastest creator of excess liquidity are going to turn much worse. We showed as much yesterday:

If the Chinese liquidity spigot – which makes the Fed’s and BOJ’s QE both pale by comparison – is indeed turned off, however briefly, then quietly look for the exit doors.

![]()

via Zero Hedge http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/zerohedge/feed/~3/BaaUyN4AYc4/story01.htm Tyler Durden

Was it really only 55 days ago that the

Was it really only 55 days ago that the In The Wall Street

In The Wall Street Heritage Foundation foreign

Heritage Foundation foreign Bad historical analogies do not convert the

Bad historical analogies do not convert the This summer, after a civil suit challenged the

This summer, after a civil suit challenged the Michael Fisher, a

Michael Fisher, a