Submitted by Gail Tverberg via Our Finite World blog,

In order to understand what solutions to our energy predicament will or won’t work, it is necessary to understand the true nature of our energy predicament. Most solutions fail because analysts assume that the nature of our energy problem is quite different from what it really is. Analysts assume that our problem is a slowly developing long-term problem, when in fact, it is a problem that is at our door step right now.

The point that most analysts miss is that our energy problem behaves very much like a near-term financial problem. We will discuss why this happens. This near-term financial problem is bound to work itself out in a way that leads to huge job losses and governmental changes in the near term. Our mitigation strategies need to be considered in this context. Strategies aimed simply at relieving energy shortages with high priced fuels and high-tech equipment are bound to be short lived solutions, if they are solutions at all.

OUR ENERGY PREDICAMENT

1. Our number one energy problem is a rapidly rising need for investment capital, just to maintain a fixed level of resource extraction. This investment capital is physical “stuff” like oil, coal, and metals.

We pulled out the “easy to extract” oil, gas, and coal first. As we move on to the difficult to extract resources, we find that the need for investment capital escalates rapidly. According to Mark Lewis writing in the Financial Times, “upstream capital expenditures” for oil and gas amounted to nearly $700 billion in 2012, compared to $350 billion in 2005, both in 2012 dollars. This corresponds to an inflation-adjusted annual increase of 10% per year for the seven year period.

Figure 1. The way would expect the cost of the extraction of energy supplies to rise, as finite supplies deplete.

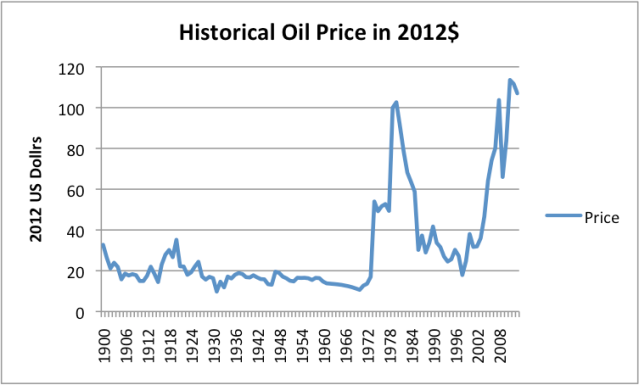

In theory, we would expect extraction costs to rise as we approach limits of the amount to be extracted. In fact, the steep rise in oil prices in recent years is of the type we would expect, if this is happening. We were able to get around the problem in the 1970s, by adding more oil extraction, substituting other energy products for oil, and increasing efficiency. This time, our options for fixing the situation are much fewer, since the low hanging fruit have already been picked, and we are reaching financial limits now.

Figure 2. Historical oil prices in 2012 dollars, based on BP Statistical Review of World Energy 2013 data. (2013 included as well, from EIA data.)

To make matters worse, the rapidly rising need for investment capital arises is other industries as well as fossil fuels. Metals extraction follows somewhat the same pattern. We extracted the highest grade ores, in the most accessible locations first. We can still extract more metals, but we need to move to lower grade ores. This means we need to remove more of the unwanted waste products, using more resources, including energy resources.

Figure 3. Waste product to produce 100 units of metal

There is a huge increase in the amount of waste products that must be extracted and disposed of, as we move to lower grade ores (Figure 3). The increase in waste products is only 3% when we move from ore with a concentration of .200, to ore with a concentration .195. When we move from a concentration of .010 to a concentration of .005, the amount of waste product more than doubles.

When we look at the inflation adjusted cost of base metals (Figure 4 below), we see that the index was generally falling for a long period between the 1960s and the 1990s, as productivity improvements were greater than falling ore quality.

Figure 4. World Bank inflation adjusted base metal index (excluding iron).

Since 2002, the index is higher, as we might expect if we are starting to reach limits with respect to some of the metals in the index.

There are many other situations where we are fighting a losing battle with nature, and as a result need to make larger resource investments. We have badly over-fished the ocean, so fishermen now need to use more resources too catch the remaining much smaller fish. Pollution (including CO2 pollution) is becoming more of a problem, so we invest resources in devices to capture mercury emissions and in wind turbines in the hope they will help our pollution problems. We also need to invest increasing amounts in roads, bridges, electricity transmission lines, and pipelines, to compensate for deferred maintenance and aging infrastructure.

Some people say that the issue is one of falling Energy Return on Energy Invested (EROI), and indeed, falling EROI is part of the problem. The steepness of the curve comes from the rapid increase in energy products used for extraction and many other purposes, as we approach limits. The investment capital limit was discovered by the original modelers of Limits to Growth in 1972. I discuss this in my post Why EIA, IEA, and Randers’ 2052 Energy Forecasts are Wrong.

2. When the amount of oil extracted each year flattens out (as it has since 2004), a conflict arises: How can there be enough oil both (a) for the growing investment needed to maintain the status quo, plus (b) for new investment to promote growth?

In the previous section, we talked about the rising need for investment capital, just to maintain the status quo. At least some of this investment capital needs to be in the form of oil. Another use for oil would be to grow the economy–adding new factories, or planting more crops, or transporting more goods. While in theory there is a possibility of substituting away from oil, at any given point in time, the ability to substitute away is quite limited. Most transport options require oil, and most farming requires oil. Construction and road equipment require oil, as do diesel powered irrigation pumps.

Because of the lack of short term substitutability, the need for oil for reinvestment tends to crowd out the possibility of growth. This is at least part of the reason for slower world-wide economic growth in recent years.

3. In the crowding out of growth, the countries that are most handicapped are the ones with the highest average cost of their energy supplies.

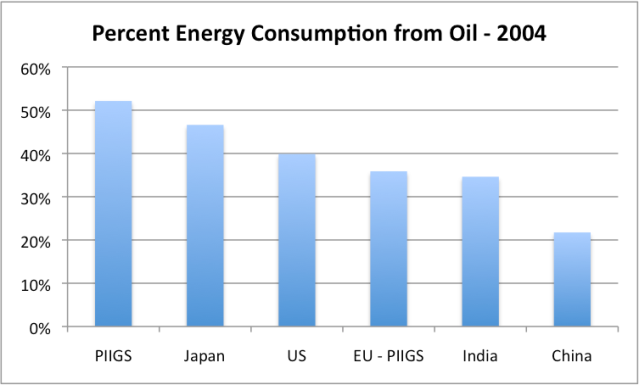

For oil importers, oil is a very high cost product, raising the average cost of energy

products. This average cost of energy is highest in countries that use the highest percentage of oil in their energy mix.

If we look at a number of oil importing countries, we see that economic growth tends to be much slower in countries that use very much oil in their energy mix. This tends to happen because high energy costs make products less affordable. For example, high oil costs make vacations to Greece unaffordable, and thus lead to cut backs in their tourist industry.

It is striking when looking at countries arrayed by the proportion of oil in their energy mix, the extent to which high oil use, and thus high cost energy use, is associated with slow economic growth (Figure 5, 6, and 7). There seems to almost be a dose response–the more oil use, the lower the economic growth. While the PIIGS (Portugal, Italy, Ireland, Greece, and Spain) are shown as a group, each of the countries in the group shows the same pattern on high oil consumption as a percentage of its total energy production in 2004.

Globalization no doubt acted to accelerate this shift toward countries that used little oil. These countries tended to use much more coal in their energy mix–a much cheaper fuel.

Figure 5. Percent energy consumption from oil in 2004, for selected countries and country groups, based on BP 2013 Statistical Review of World Energy. (EU – PIIGS means “EU-27 minus PIIGS’)

Figure 6. Average percent growth in real GDP between 2005 and 2011, based on USDA GDP data in 2005 US$.

Figure 7. Average percentage consumption growth between 2004 and 2011, based on BP’s 2013 Statistical Review of World Energy.

4. The financial systems of countries with slowing growth are especially affected, as are the governments. Debt becomes harder to repay with interest, as economic growth slows.

With slow growth, debt becomes harder to repay with interest. Governments are tempted to add programs to aid their citizens, because employment tends to be low. Governments find that tax revenue lags because of the lagging wages of most citizens, leading to government deficits. (This is precisely the problem that Turchin and Nefedov noted, prior to collapse, when they analyzed eight historical collapses in their book Secular Cycles.)

Governments have recently attempt to fix both their own financial problems and the problems of their citizens by lowering interest rates to very low levels and by using Quantitative Easing. The latter allows governments to keep even long term interest rates low. With Quantitative Easing, governments are able to keep borrowing without having a market of ready buyers. Use of Quantitative Easing also tends to blow bubbles in prices of stocks and real estate, helping citizens to feel richer.

5. Wages of citizens of countries oil importing countries tend to remain flat, as oil prices remain high.

At least part of the wage problem relates to the slow economic growth noted above. Furthermore, citizens of the country will cut back on discretionary goods, as the price of oil rises, because their cost of commuting and of food rises (because oil is used in growing food). The cutback in discretionary spending leads to layoffs in discretionary sectors. If exported goods are high priced as well, buyers from other countries will tend to cut back as well, further leading to layoffs and low wage growth.

6. Oil producers find that oil prices don’t rise high enough, cutting back on their funds for reinvestment.

As oil extraction costs increase, it becomes difficult for the demand for oil to remain high, because wages are not increasing. This is the issue I describe in my post What’s Ahead? Lower Oil Prices, Despite Higher Extraction Costs.

We are seeing this issue today. Bloomberg reports, Oil Profits Slump as Higher Spending Fails to Raise Output. Business Week reports Shell Surprise Shows Profit Squeeze Even at $100 Oil. Statoil, the Norwegian company, is considering walking away from Greenland, to try to keep a lid on production costs.

7. We find ourselves with a long-term growth imperative relating to fossil fuel use, arising from the effects of globalization and from growing world population.

Globalization added approximately 4 billion consumers to the world market place in the 1997 to 2001 time period. These people previously had lived traditional life styles. Once they became aware of all of the goods that people in the rich countries have, they wanted to join in, buying motor bikes, cars, televisions, phones, and other goods. They would also like to eat meat more often. Population in these countries continues to grow adding to demand for goods of all kinds. These goods can only be made using fossil fuels, or by technologies that are enabled by fossil fuels (such as today’s hydroelectric, nuclear, wind, and solar PV).

8. The combination of these forces leads to a situation in which economies, one by one, will turn downward in the very near future–in a few months to a year or two. Some are already on this path (Egypt, Syria, Greece, etc.)

We have two problems that tend to converge: financial problems that countries are now hiding, and ever rising need for resources in a wide range of areas that are reaching limits (oil, metals, over-fishing, deferred maintenance on pipelines).

On the financial side, we have countries trying to hang together despite a serious mismatch between revenue and expenses, using Quantitative Easing and ultra-low interest rates. If countries unwind the Quantitative Easing, interest rates are likely to rise. Because debt is widely used, the cost of everything from oil extraction to buying a new home to buying a new car is likely to rise. The cost of repaying the government’s own debt will rise as well, putting governments in worse financial condition than they are today.

A big concern is that these problems will carry over into debt markets. Rising interest rates will lead to widespread defaults. The availability of debt, including for oil drilling, will dry up.

Even if debt does not dry up, oil companies are already being squeezed for investment funds, and are considering cutting back on drilling. A freeze on credit would make certain this happens.

Meanwhile, we know that investment costs keep rising, in many different industries simultaneously, because we are reaching the limits of a finite world. There are more resources available; they are just more expensive. A mismatch occurs, because our wages aren’t going up.

The physical amount of oil needed for all of this investment keeps rising, but oil production continues on its relativ

ely flat plateau, or may even begins to drop. This leads to less oil available to invest in the rest of the economy. Given the squeeze, even more countries are likely to encounter slowing growth or contraction.

9. My expectation is that the situation will end with a fairly rapid drop in the production of all kinds of energy products and the governments of quite a few countries failing. The governments that remain will dramatically cut services.

With falling oil production, promised government programs will be far in excess of what governments can afford, because governments are basically funded out of the surpluses of a fossil fuel economy–the difference between the cost of extraction and the value of these fossil fuels to society. As the cost of extraction rises, the surpluses tend to dry up.

Figure 8. Cost of extraction of barrel oil, compared to value to society. Economic growth is enabled by the difference.

As these surpluses shrink, governments will need to shrink back dramatically. Government failure will be easier than contracting back to a much smaller size.

International finance and trade will be particularly challenging in this context. Trying to start over will be difficult, because many of the new countries will be much smaller than their predecessors, and will have no “track record.” Those that do have track records will have track records of debt defaults and failed promises, things that will not give lenders confidence in their ability to repay new loans.

While it is clear that oil production will drop, with all of the disruption and a lack of operating financial markets, I expect natural gas and coal production will drop as well. Spare parts for almost anything will be difficult to get, because of the need for the system of international trade to support making these parts. High tech goods such as computers and phones will be especially difficult to purchase. All of these changes will result in a loss of most of the fossil fuel economy and the high tech renewables that these fossil fuels support.

A Forecast of Future Energy Supplies and their Impact

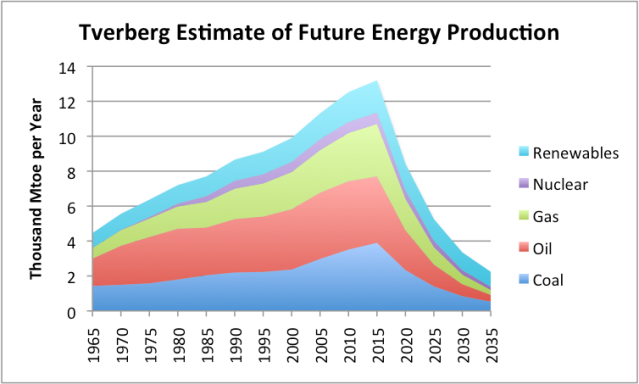

A rough estimate of the amounts by which energy supply will drop is given in Figure 9, below.

Figure 9. Estimate of future energy production by author. Historical data based on BP adjusted to IEA groupings.

The issue we will be encountering could be much better described as “Limits to Growth” than “Peak Oil.” Massive job layoffs will occur, as fuel use declines. Governments will find that their finances are even more pressured than today, with calls for new programs at the time revenue is dropping dramatically. Debt defaults will be a huge problem. International trade will drop, especially to countries with the worst financial problems.

One big issue will be the need to reorganize governments in a new, much less expensive way. In some cases, countries will break up into smaller units, as the Former Soviet Union did in 1991. In some cases, the situation will go back to local tribes with tribal leaders. The next challenge will be to try to get the governments to act in a somewhat co-ordinated way. There may need to be more than one set of governmental changes, as the global energy supplies decline.

We will also need to begin manufacturing goods locally, at a time when debt financing no longer works very well, and governments are no longer maintaining roads. We will have to figure out new approaches, without the benefit of high tech goods like computers. With all of the disruption, the electric grid will not last very long either. The question will become: what can we do with local materials, to get some sort of economy going again?

NON-SOLUTIONS and PARTIAL SOLUTIONS TO OUR PROBLEM

There are a lot of proposed solutions to our problem. Most will not work well because the nature of the problem is different from what most people have expected.

1. Substitution. We don’t have time. Furthermore, whatever substitutions we make need to be with cheap local materials, if we expect them to be long-lasting. They also must not over-use resources such as wood, which is in limited supply.

Electricity is likely to decline in availability almost as quickly as oil because of inability to keep up the electrical grid and other disruptions (such as failing governments, lack of oil to lubricate machinery, lack of replacement parts, bankruptcy of companies involved with the production of electricity) so is not really a long-term solution to oil limits.

2. Efficiency. Again, we don’t have time to do much. Higher mileage cars tend to be more expensive, replacing one problem with another. A big problem in the future will be lack of road maintenance. Theoretical gains in efficiency may not hold in the real world. Also, as governments reduce services and often fail, lenders will be unwilling to lend funds for new projects which would in theory improve efficiency.

In some cases, simple devices may provide efficiency. For example, solar thermal can often be a good choice for heating hot water. These devices should be long-lasting.

3. Wind turbines. Current industrial type wind turbines will be hard to maintain, so are unlikely to be long-lasting. The need for investment capital for wind turbines will compete with other needs for investment capital. CO2 emissions from fossil fuels will drop dramatically, with or without wind turbines.

On the other hand, simple wind mills made with local materials may work for the long term. They are likely to be most useful for mechanical energy, such as pumping water or powering looms for cloth.

4. Solar Panels. Promised incentive plans to help homeowners pay for solar panels can be expected to mostly fall through. Inverters and batteries will need replacement, but probably will not be available. Handy homeowners who can rewire the solar panels for use apart from the grid may find them useful for devices that can run on direct current. As part of the electric grid, solar panels will not add to its lifetime. It probably will not be possible to make solar panels for very many years, as the fossil fuel economy reaches limits.

5. Shale Oil. Shale oil is an example of a product with very high investment costs, and returns which are doubtful at best. Big companies who have tried to extract shale oil have decided the rewards really aren’t there. Smaller companies have somehow been able to put together financial statements claiming profits, based on hoped for future production and very low interest rates.

Costs for extracting shale oil outside the US for shale oil are likely to be even higher than in the US. This happens because the US has laws that enable production (landowner gets a share of profits) and other beneficial situations such as pipelines in place, plentiful water supplies, and low population in areas where fracking is done. If countries decide to ramp up shale oil production, they are likely to run into similarly hugely negative cash flow situations. It is hard to see that these operations will save the world from its financial (and energy) pr

oblems.

6. Taxes. Taxes need to be very carefully structured, to have any carbon deterrent benefit. If part of taxes consumers would normally pay to the government are levied on fuel for vehicles, the practice can encourage more the use of more efficient vehicles.

On the other hand, if carbon taxes are levied on businesses, the taxes tend to encourage businesses to move their production to other, lower-cost countries. The shift in production leads to the use of more coal for electricity, rather than less. In theory, carbon taxes could be paired with a very high tax on imported goods made with coal, but this has not been done. Without such a pairing, carbon taxes seem likely to raise world CO2 emissions.

7. Steady State Economy. Herman Daly was the editor of a book in 1973 called Toward a Steady State Economy, proposing that the world work toward a Steady State economy, instead of growth. Back in 1973, when resources were still fairly plentiful, such an approach would have acted to hold off Limits to Growth for quite a few years, especially if zero population growth were included in the approach.

Today, it is far too late for such an approach to work. We are already in a situation with very depleted resources. We can’t keep up current production levels if we want to–to do so would require greatly ramping up energy production because of the rising need for energy investment to maintain current production, discussed in Item (1) of Our Energy Predicament. Collapse will probably be impossible to avoid. We can’t even hope for an outcome as good as a Steady State Economy.

7. Basing Choice of Additional Energy Generation on EROI Calculations. In my view, basing new energy investment on EROI calculations is an iffy prospect at best. EROI calculations measure a theoretical piece of the whole system–”energy at the well-head.” Thus, they miss important parts of the system, which affect both EROI and cost. They also overlook timing, so can indicate that an investment is good, even if it digs a huge financial hole for organizations making the investment. EROI calculations also don’t consider repairability issues which may shorten real-world lifetimes.

Regardless of EROI indications, it is important to consider the likely financial outcome as well. If products are to be competitive in the world marketplace, electricity needs to be inexpensive, regardless of what the EROI calculations seem to say. Our real problem is lack of investment capital–something that is gobbled up at prodigious rates by energy generation devices whose costs occur primarily at the beginning of their lives. We need to be careful to use our investment capital wisely, not for fads that are expensive and won’t hold up for the long run.

8. Demand Reduction. This really needs to be the major way we move away from fossil fuels. Even if we don’t have other options, fossil fuels will move away from us. Encouraging couples to have smaller families would seem to be a good choice.

via Zero Hedge http://ift.tt/1acnrhN Tyler Durden

The New York Times’

Farrow’s letter concludes: