Human Rights Watch got their hands on an app used by Chinese authorities in the western Xinjiang region to surveil, track and categorize the entire local population – particularly the 13 million or so Turkic Muslims subject to heightened scrutiny, of which around one million are thought to live in ‘reeducation’ camps.

By “reverse engineering” the code in the “Integrated Joint Operations Platform” (IJOP) app, HRW was able to identify the exact criteria authorities rely on to ‘maintain social order.’ Of note, IJOP is “central to a larger ecosystem of social monitoring and control in the region,” and similar to systems being deployed throughout the entire country.

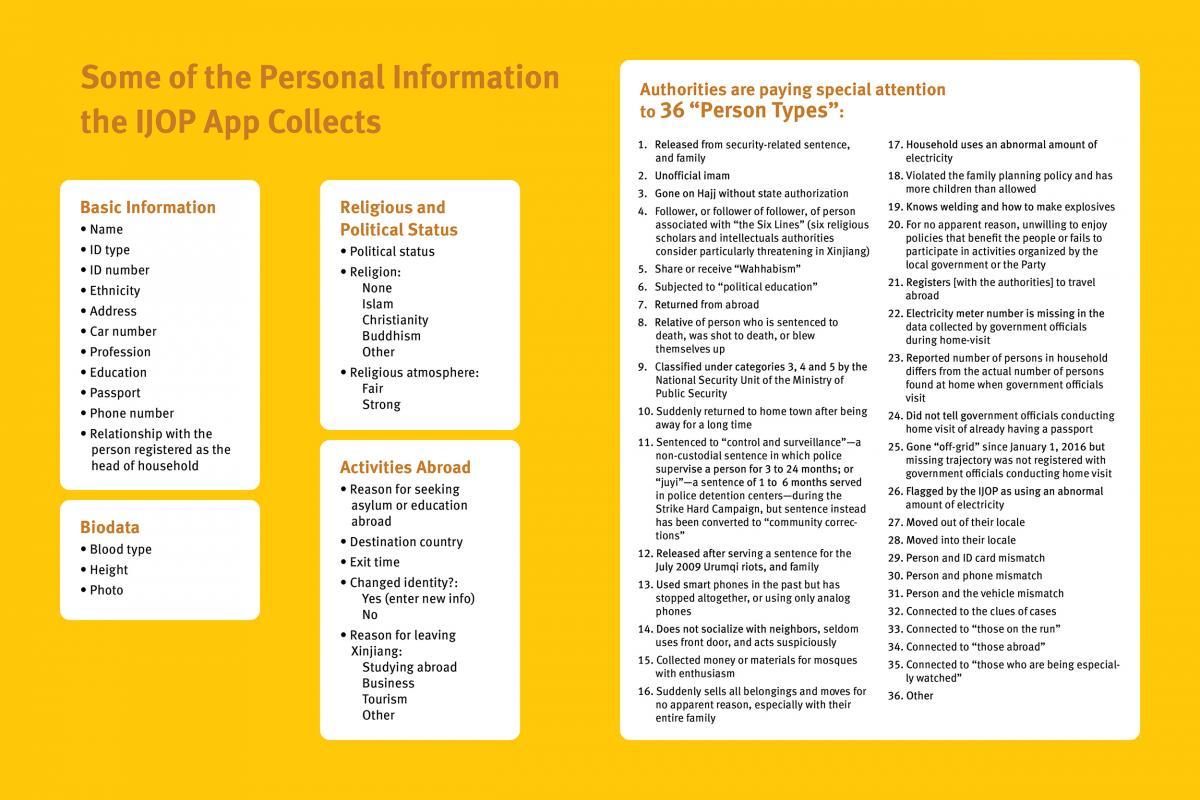

The platform targets 36 types of people for data collection, from those who have “collected money or materials for mosques with enthusiasm,” to people who stop using smartphones.

[A]uthorities are collecting massive amounts of personal information—from the color of a person’s car to their height down to the precise centimeter—and feeding it into the IJOP central system, linking that data to the person’s national identification card number. Our analysis also shows that Xinjiang authorities consider many forms of lawful, everyday, non-violent behavior—such as “not socializing with neighbors, often avoiding using the front door”—as suspicious. The app also labels the use of 51 network tools as suspicious, including many Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) and encrypted communication tools, such as WhatsApp and Viber. –Human Rights Watch

Another method of tracking is the “Four Associations”

The IJOP app suggests Xinjiang authorities track people’s personal relationships and consider broad categories of relationship problematic. One category of problematic relationships is called “Four Associations” (四关联), which the source code suggests refers to people who are “linked to the clues of cases” (关联案件线索), people “linked to those on the run” (关联在逃人员), people “linked to those abroad” (关联境外人员), and people “linked to those who are being especially watched” (关联关注人员). –HRW

*An extremely detailed look at the data collected and how the app works can be found in the actual report.

HRW notes that “Many—perhaps all—of the mass surveillance practices described in this report appear to be contrary to Chinese law, and also violate internationally guaranteed rights to privacy, the presumption of innocence, and freedom of association and movement. “Their impact on other rights, such as freedom of expression and religion, is profound,” according to the report.

Here’s what happens when ‘irregularities’ are detected:

When IJOP detects a deviation from normal parameters, such as when a person uses a phone not registered to them, or when they use more electricity than what would be considered “normal,” or when they travel to an unauthorized area without police permission, the system flags them as “micro-clues” which authorities use to gauge the level of suspicion a citizen should fall under.

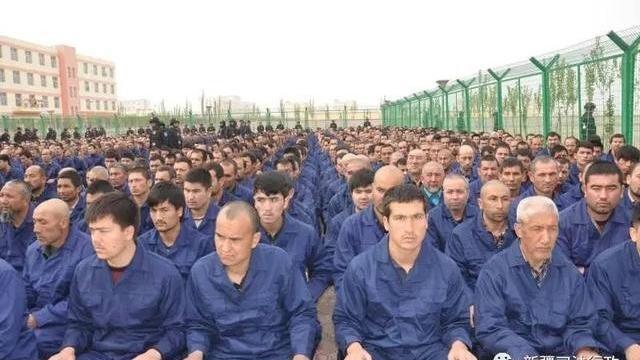

© 2018 Darren Byler

IJOP also monitors personal relationships – some of which are deemed inherently suspicious, such as relatives who have obtained new phone numbers or who maintain foreign links.

Chinese authorities justify the surveillance as a means to fight terrorism. To that end, IJOP checks for terrorist content and “violent audio-viusual content” when surveilling phones and software. It also flags “adherents of Wahhabism,” the ultra-conservative form of Islam accused of being a “source of global terrorism.”

A former Xinjiang resident told Human Rights Watch a week after he was released from arbitrary detention: “I was entering a mall, and an orange alarm went off.” The police came and took him to a police station. “I said to them, ‘I was in a detention center and you guys released me because I was innocent.’… The police told me, ‘Just don’t go to any public places.’… I said, ‘What do I do now? Just stay home?’ He said, ‘Yes, that’s better than this, right?’” –Human Rights Watch

The IJOP system was developed by a major-state owned military contractor – the China Electronics Technology Group Corporation (CETC). The app itself was developed by Hebei Far East Communication System Engineering Company (HBFEC), a company that, at the time of the app’s development, was fully owned by CETC.

Credit: Joanne Smith Finley

Meanwhile, under the broader “Strike Hard Campaign,“ authorities in Xinjiang are also collecting “biometrics, including DNA samples, fingerprints, iris scans, and blood types of all residents in the region ages 12 to 65,” according to the report, which adds that “the authorities require residents to give voice samples when they apply for passports.“

The Strike Hard Campaign has shown complete disregard for the rights of Turkic Muslims to be presumed innocent until proven guilty. In Xinjiang, authorities have created a system that considers individuals suspicious based on broad and dubious criteria, and then generates lists of people to be evaluated by officials for detention. Official documents state that individuals “who ought to be taken, should be taken,” suggesting the goal is to maximize the number of people they find “untrustworthy” in detention. Such people are then subjected to police interrogation without basic procedural protections. They have no right to legal counsel, and some are subjected to torture and mistreatment, for which they have no effective redress, as we have documented in our September 2018 report. The result is Chinese authorities, bolstered by technology, arbitrarily and indefinitely detaining Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang en masse for actions and behavior that are not crimes under Chinese law.

Read the entire report from Human Rights Watch here.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2Jfw9BV Tyler Durden