Submitted by David Stockman via Contra Corner blog,

Once in a blue moon officials commit truth in public, but the intrepid leader of Germany’s central bank has delivered a speech which let’s loose of three of them in a single go. Speaking at a conference in Riga, Latvia, Jens Weidmann put the kibosh on QE, low-flation and central bank interference in pricing of risky assets.

These days the Keynesian chorus in favor of policy activism is so boisterous that a succinct statement to the contrary rarely gets through – especially at Rupert Murdoch’s Wall Street yarn factory. But here’s what penetrated even Brian Blackstone’s filters:

“The biggest bottleneck for growth in the euro area is not monetary policy, nor is it the lack of fiscal stimulus: it is the structural barriers that impede competition, innovation and productivity,” he said.

Needless to say, that is not only the truth but its one that is distinctly unwelcome to the policy apparatchiks in Brussels and the politicians in virtually every European capital. Self-evidently, printing money and running up the public debt are pleasurable and profitable tasks for agents of state intervention. But reducing “structural barriers” like restrictive labor laws, private cartel arrangements and inefficiency producing crony capitalist raids on the public till are a different matter altogether. In the political arena, they involve too much short-term pain to achieve the long-run gain.

But implicit in Weidmann’s plain and truthful declaration is an even more important proposition. Namely, rejection of the mechanistic Keynesian notion that the state is responsible for every last decimal point of the GDP growth rate. Indeed, the latter has now become such an overwhelming consensus in the political capitals that to suggest doing nothing on the “stimulus” front sounds almost quaint—-a throwback to the long-ago and purportedly benighted times of laissez faire.

But perhaps stolid German statesmen like Weidmann remember a thing or two about history, and have noted that what is failing in the present era is not private capitalism, but the bloated omnipresent public state. And having almost uniquely among DM nations resisted the siren song of Keynesian activism, Germans can also observe that their economy has not plunged into some depressionary dark hole for want of sufficient fiscal activism.

Undoubtedly, they can also note that by refusing to take the Keynesian bait, Germany has achieved a level of fiscal rectitude that is utterly unique in recent years—–especially since the great financial crisis of 2008. For good reason, therefore, Germany does not want to subsidize the fiscal irresponsibility of the rest of the EU, but that’s exactly what would happen under the Bernanke style QE that Weidmann so stoutly resists.

Unlike the bevies of Keynesian cool-aid drinkers who dominate policy in Brussels and throughout the rest of Europe, Weidmann recognizes the truth that central banks have not abolished the laws of supply and demand, and that massive bond buying under QE creates a false bid and false price for public debt. That his antagonist, Mario Draghi, remains utterly clueless about this elementary point is perhaps explainable by their variant histories. To wit, other than his brief period as a highly paid trainee at Goldman Sachs, Draghi spent many years as a top official in the Italian treasury.

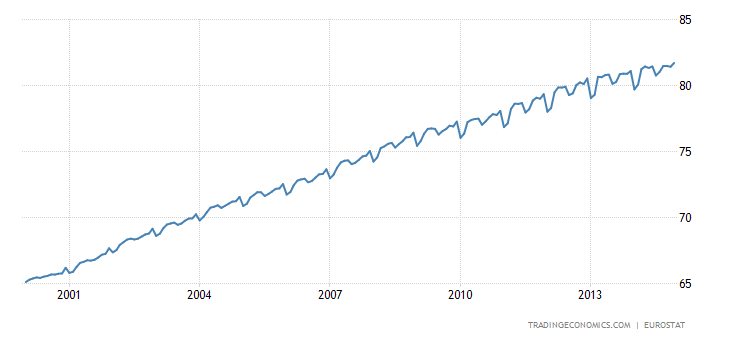

In that respect, sometimes chart pictures are indeed worth a thousand words and here is a dramatic case in point. Unconsciously or otherwise, Draghi represents the financial culture of a state which has already crossed the fiscal Rubicon, so to speak. The average interest rate on Italy’s mountainous debt is still about 4%, meaning that at its 135% debt-to-GDP ratio, Italy needs 5-6% nominal income growth every year just to tread water—-even if it runs a consistent “primary” budget surplus.

But Italy’s nominal GDP has not grown at all during the last 7 years, and has no prospect whatsoever of bursting out of the blocks at a 5-6% rate of growth. So the only way it can survive is by means of constant and massive financial repression by the ECB. Notwithstanding all of the gumming about “low-flation” and the monetary hobgoblins of the 1930s, Draghi’s drive to push the ECB into outright QE and to massively re-expand its balance sheet by purchasing peripheral debt is about one thing alone. Namely, the monetization of public debt that can no longer be serviced by current taxes—or at least taxes that the pampered and cowardly politicians in Rome, Madrid and elsewhere are willing to impose on their electorates.

At the end of the day, here is the reason Weidmann has issued once again a loud and pointed “nein!” with respect to QE.

While he was at it, Weidman spoke the truth about the low-flation pretext for more money printing by the ECB, as well.

“The low inflationary pressure is for a large part due to the decline in energy prices and the adjustment processes in some euro-area countries—factors beyond the direct influence of the [ECB’s] monetary policy,” he said.

Undoubtedly, Herr Weidmann is aware of the facts. Here is the longer-term trend of for core inflation—ex energy and food—for the Eurozone. Yes, consumers are enjoying a temporary respite from high oil, commodity and other import prices. But as Weidman well knows there is no “specter of deflation” haunting Europe.

Finally, Weidmann landed a solid punch on Draghi’s scheme to pursue QE through the back door of buying what amounts to junk bonds on the secondary market. The the President of the Bundesbank rightly said that the ECB’s program to purchases bundles of loans to households and businesses, with the aim of raising money supply and boosting the flow of credit to the private sector—-

” transfers risks from financial institutions to the central bank and, ultimately, taxpayers. This would run counter to everything we have strived to achieve in banking regulation over the last years…..”

Kudos To Herr Weidmann For Uttering Three Truths In One Speech

by Brian Blackstone at the Wall Street Journal

German central bank President Jens Weidmann reiterated his opposition to the European Central Bank’s recent decision to purchase large sums of asset-backed securities, saying the program undermines efforts made in banking regulation.

In prepared comments to a conference in Riga, Latvia, Mr. Weidmann said he doesn’t see risks of persistent declines in consumer prices, known as deflation, though there is a risk of inflation staying too low for too long.

He urged governments to enact structural reforms to improve their economies, and pushed back against calls for Germany to enact more stimulus to beef up its economy.

“The biggest bottleneck for growth in the euro area is not monetary policy, nor is it the lack of fiscal stimulus: it is the structural barriers that impede competition, innovation and productivity,” he said.

Last month, the ECB unveiled a program to purchases bundles of loans to households and businesses, with the aim of raising money supply and boosting the flow of credit to the private sector. Mr. Weidmann opposed the decision, saying it transfers risks from financial institutions to the central bank and, ultimately, taxpayers.

“This would run counter to everything we have strived to achieve in banking regulation over the last years,” he said.

Mr. Weidmann, who sits on the ECB’s 24-member governing council, signaled he has little, if any, appetite for more dramatic measures despite annual eurozone inflation rates that are far below the ECB’s target of just below 2%. Consumer prices were up 0.3% in September from one year earlier, a five-year low.

“The low inflationary pressure is for a large part due to the decline in energy prices and the adjustment processes in some euro-area countries—factors beyond the direct influence of the [ECB’s] monetary policy,” he said.

The ECB should only respond if this weakness extends to prices more broadly, he said, which economists refer to as second-round effects.

Read more here – http://ift.tt/1rKAqsO

via Zero Hedge http://ift.tt/1rKAnxk Tyler Durden