Almost four years ago we pointed out something striking: while the world was still busy recovering from the covid Pandemic and suffering under soaring inflation – as seemingly everything was suddenly in short supply and prices were soaring – China was busy stockpiling pretty much everything at an unprecedented pace. Quoting a JPM report from March 2022 we noted that “while the world is short on commodities, China is not given they have started stockpiling commodities since 2019 and currently hold 80% of global copper inventories, 70% of corn, 51% of wheat, 46% of soybeans, 70% of crude oil, and over 20% of global aluminum inventories.”

Almost as if China was preparing for its inevitable invasion of Taiwan.

But if anyone expected China to ease off the hoarding pedal after its massive stockpiling spree, they would be very disappointed and nowhere more so than oil. As John Kemp of JKemp Energy notes, China has been accumulating crude oil inventories to take advantage of relatively low prices and act as an emergency reserve in any future conflict with the United States and its allies.

China’s stocks of crude oil apparently increased by 54 million tonnes (about 400 million barrels or 1.1 million barrels per day) during 2025 after a similar increase in 2024. China’s massive inventory build-up has helped avert the accumulation of stocks in other areas and limited the fall in prices even as Saudi Arabia and its OPEC partners have boosted production.

Inventory accumulation, Kemp writes echoing what we said years ago, has also been described as a “strategic warning indicator” that could indicate the country’s leaders are preparing for a future conflict with the United States over Taiwan.

“Energy production and stockpile buildups often precede great power industrial wars,” one analyst told the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission established by the U.S. Congress.

In building strategic reserves to enable its economy to keep functioning and armed forces to keep fighting during a future conflict, the country is following long-standing precedent.

China, of course, is not alone: policymakers and military planners in the United States, Britain, France and other countries in Western Europe as well as Japan have all focused on building oil reserves in readiness for a conflict for almost a century. Yet nobody has taken stockpiling as religiously as Beijing has in recent years.

SECRETIVE STOCKS

China’s government considers stocks of crude and refined products stored by importers, refiners and distributors as well as its own strategic reserves a state secret. Total inventories are not disclosed which has led to a guessing game about how much oil is stored and its distribution between commercial stocks (held for operational and speculative purposes) and strategic reserves.

But it is possible to obtain some indication about the magnitude and direction of changes from data the government does publish on domestic crude production, imports and processing by refineries.

Crude oil exports and the direct use of crude by industry have fallen to negligible levels in recent years so they can be safely ignored.

In 2025, China’s domestic crude output climbed to 216 million tonnes and the country imported a further 578 million, according to data published by National Bureau of Statistics and the General Administration of Customs.

But the country’s refineries processed only 738 million tonnes, leaving 56 million unaccounted for, of which perhaps 2 million were probably exported with other small volumes used directly in industry.

Meanwhile, since the start of the century, China has apparently increased its crude inventories in 24 of the 25 years, according to an analysis of government data. The exception was 2021, after an unprecedented increase the previous year, during the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic, which caused crude prices to slump to multi-decade lows.

The persistent rise can be explained in part by operational requirements stemming from the growing consumption of gasoline, diesel and other petroleum products. But consumption has grown more slowly in recent years as deployment of electric vehicles and gas-powered trucks has cut into fuel use.

The apparent increase in stocks during 2024 and again in 2025 is too large to be attributed to operational needs and commercial incentives alone.

The massive accumulation appears to be “a precautionary measure in case imports are disrupted by sanctions or an embargo during any future conflict with the United States and its allies,” Kemp writes.

ENERGY SECURITY

China imports more than 70% of the crude processed in its refineries and the government has identified this foreign dependence a critical issue for national security. The Communist Party’s Central Committee recently issued a call for “Building a Strong Energy Nation” as part of its formal input into drafting the Fifteenth Five-Year Plan covering the years from 2026 to 2030:

“[E]nergy security and stability are of paramount importance to the national economy and people’s livelihoods, and are a matter of utmost national importance that cannot be ignored.”

“Currently, the world is undergoing profound changes unseen in a century, with technological revolutions and great power competition intertwined, deeply reshaping the global energy supply and demand landscape.”

There is “an urgent requirement for enhancing energy security and gaining the initiative in great power competition. Currently, frequent regional conflicts exacerbate geopolitical risks, and the United States continues to contain and suppress China, making the politicization and weaponization of energy issues more prominent.”

“To prevent shocks in the energy sector and effectively guarantee domestic development, my country’s energy system must improve its own development level and security capabilities.”

“Building a strong energy nation … is the only way for my country to achieve fundamental energy security,” the Central Committee concluded.

OIL IN WARTIME

Throughout history, governments have accumulated stocks of critical materials as well as armaments in preparation for conflicts. Strategic stockpiling is arguably one of the core functions of the state. From antiquity to the medieval period, walled cities and fortresses stockpiled water, food and fuel to help withstand a prolonged siege; defensive walls without stocks of critical supplies were an invitation to famine.

Since the First World War, which saw the first widespread use of oil for battleships and other transport, the preoccupation with stockpiling has applied to oil as well.

Modern governments have accumulated strategic reserves as well as encouraging domestic oil production and incentivising alternative fuels as to protect their economies and warfighting ability in the event of conflict.

“Petroleum will continue to be the most essential fuel of industry in both peace and war,” the U.S. Senate’s Special Committee Investigating Petroleum Resources concluded in 1947. “No nation which lacks a sure supply of liquid fuel can hope to maintain a position of leadership among the peoples of the world.”

“In time of peace a nation, to maintain a first-class rating in the trade and commerce of the modern world, must have access to an abundant supply of oil because mechanized industry and transportation depend upon it. Oil is also of basic importance for purposes other than the provision of energy. Petroleum lubricates the fleets, airplanes, and machines of the world. It is a raw material in the whole field of chemicals. It is used in the manufacture of pharmaceutical products, paints, solvents, plastics, and synthetic rubber.”

“In time of war, as twice demonstrated on a large scale in the present century, a nation, to remain a first-class Power, must have petroleum resources immediately and continuously available in virtually unlimited volume. Oil is the sine qua non of military victory.

For countries with limited production on their own territory, relying on imports, ensuring uninterrupted supplies has usually meant accumulating strategic stocks to be drawn down in the event imports are disrupted.

PRE-WAR PLANNING

Since 1928, French law has required the permanent availability of three months of oil stocks with the aim of being “energy independent in case of crisis”.

In Britain, the Royal Commission on Fuel and Engines stressed the importance of holding large stocks in reserve as early as 1913 as the Royal Navy shifted its fuel from domestically produced coal to imported petroleum.

In 1934, the Oil Board, a subcommittee of the Committee of Imperial Defence, Britain’s top military planning body, was instructed to prepare plans for a war against a European enemy with a target date of 1 January 1940.

The Oil Board recommended the Royal Navy, the Army and the Royal Air Force should each lay in stocks equivalent to six months of wartime consumption (later raised to as much as one year in the case of the Air Force).

The Oil Board also recommended Britain’s oil companies should raise their own stocks to the equivalent of three months of peacetime consumption, a recommendation subsequently accepted by the industry.

In 1938, Britain’s Parliament approved the Essential Commodities Reserves Act, which gave the government power to obtain information about commodities vital in the event of war and make provisions for reserves.

In agreement with the Treasury, the act authorized the Board of Trade to make payments or loans to traders to encourage them to hold increased stocks of essential commodities, or acquire and own them its own right.

IEA EMERGENCY STOCKS

The idea of holding oil reserves equivalent to three months of consumption or net imports has remained a benchmark incorporated into subsequent iterations of strategic reserves. In 1974, following the Arab oil embargo the previous year, the governments of the United States, Japan and Western Europe concluded an Agreement on an International Energy Program.

Each participating country committed to maintain “emergency reserves sufficient to sustain consumption for at least 60 days with no net oil imports” (later raised to 90 days or three months).

The emergency reserve requirement could be satisfied by oil stocks, fuel switching capacity, or stand-by oil production.

The agreement also created a Standing Group on Emergency Questions and an International Energy Agency (IEA) to oversee and implement the programme.

In the United States, the agreement was given effect by the 1975 Energy Policy and Conservation Act, which established the government-owned and run Strategic Petroleum Reserve.

In the United Kingdom, it was given effect by the 1976 Energy Act, which gave the government powers to order oil suppliers or users to maintain stocks at a minimum specified level.

Similar legislation was enacted in the other participating countries – in most cases requiring oil producers, importers, distributors or users to maintain stocks at minimum levels, either themselves or by agreement with third parties.

CHINA’S ESTIMATED STOCKS

Between 2023 and 2025, China imported between 4.1 billion and 4.2 billion barrels of crude each year, according to data from the General Administration of Customs. China’s supplies are extremely vulnerable given it relies on imports mostly along sea lanes in the Middle East, Indian Ocean and South China Sea patrolled by the U.S. Navy and allies.

Policymakers have followed their western counterparts in trying to lessen the risks by building commercial and strategic reserves at tank farms near ports and refineries as well as below ground to protect them from air attack. By mid-2024, China’s total crude storage capacity at tank farms was estimated at more than 1.8 billion barrels by consultants Kayrros and shared in prepared testimony to the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission.

Between 2016 and 2024, China’s observed stocks above ground had ranged between 850 million and a little over 1 billion barrels, according to Kayrros, using geospatial analysis on the roofs of floating roofs at tank farms. Above ground inventories included approximately 200 million barrels of strategic reserves at various sites. There was also below ground storage in at least four locations with the capacity to store another 100 million barrels.

China’s observed and estimated oil inventories are a combination of commercial stocks (held for operational and speculative purposes) and strategic stocks (held in readiness for any future disruption of imports). More recently, in March 2025, the country’s commercial stocks were estimated at around 670 million barrels, with a further 400 million held as strategic reserves, according to Kayrros.

The country also had underground facilities capable of holding a further 130 million barrels with an unknown fill rate.

Total inventories were estimated at between 1.1 billion and 1.2 billion barrels – equivalent to around 100 days or just over three months of imports. But the country’s above ground storage facilities were less than 60% full at the time, implying there was scope to increase stocks further.

China continued to import crude in excess of its refinery requirements throughout the rest of 2025 implying inventories had been raised even higher by the end of the year.

LACK OF TRANSPARENCY

Stockpiling can contribute to strategic stability or instability depending on point of view: it may make governments feel more secure and less prone to strike first, or embolden them to engage in more aggressive and risky behavior.

China’s policymakers have always considered the exact amount of oil held in commercial and strategic storage to be a matter of national security and a state secret. Secrecy is understandable given the country’s extreme vulnerability to any interruption of imports; there is no benefit sharing inventory levels with potential adversaries.

But the lack of transparency has fueled suspicions about the country’s intentions and whether stockpiling is defensive in nature or indicates a more aggressive preparation for war.

“China’s outsized oil storage expansion … has profound strategic implications,” one analyst testified to the Economic and Strategic Review Commission, because it can “dramatically enhance China’s ability to weather an oil blockade.”

There is also ambiguity about the distribution and management of commercial compared with strategic stocks. China’s oil inventories are much less transparent than those of the United States and other IEA members, but the stockholding arrangements themselves are not that unusual.

“Nine clearly demarcated SPR bases exist, but often sit adjacent to far larger commercial tank capacity. The stocks share access to common pipeline infrastructure and refineries.”

The somewhat ambiguous relationship between commercial and strategic inventories is not that unusual. Nor is co-location and sharing pipelines and refineries. Crude oil is not useful without access to refineries and pipelines for long-distance transmission and distribution so sharing infrastructure makes sense.

IEA members themselves employ a variety of models for maintaining strategic reserves – owned and run by the government itself, by industry, or by specialised stockholding agencies and third parties. The purpose of strategic stocks has always been somewhat ambiguous and has become more so over time as policymakers have sought to use them more actively.

Most IEA members hold stocks to deal with military and economic emergencies – outright supply interruptions as well as sudden spikes in prices. It is not always easy to distinguish between them.

GLOBAL MARKET IMPACT

China is the world’s second-largest oil consumer (after the United States) and by far the world’s largest crude importer, so the country’s consumption and inventories have a significant impact on global balances. Lack of transparency about the size of inventories, their purpose, and future trends has become a major source of uncertainty for the oil industry.

There is some evidence purchases by China’s refiners and possibly its stockpile managers have been sensitive to prices – with imports accelerating when prices have been relatively low. But this has been based on empirical observations of the rate of imports rather than a firm understanding of inventory management policies.

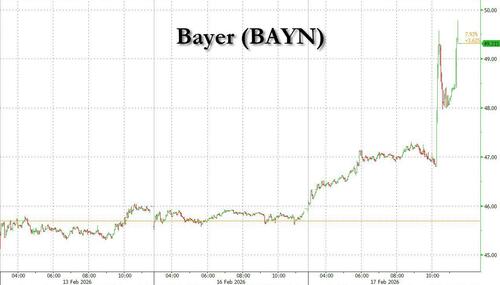

China’s rapid imports in 2025 absorbed some of the surplus oil production as Saudi Arabia and its OPEC⁺ partners boosted output rapidly in the face of tepid global consumption.

China’s inventory building has been described as “a secondary source of oil demand” by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). By absorbing some excess production and removing it from the open market, at least for now, stockpiling probably prevented a much faster and deeper decline in prices, especially in the spot market.

China’s inventory accumulation may have helped stabilize prices, informally and unintentionally making the country a market adjuster or buffer stock manager. But the scale and timing of future changes in both commercial and strategic inventories remain unknown and difficult to forecast.

If purchases for inventory are sensitive to prices, China might accelerate them if prices decline further (subject to logistics constraints) or taper them if prices rise. Price-sensitive purchasing policies would help dampen volatility again.

The EIA has said that: “We assume that China will continue building strategic stockpiles at nearly the same rate of about 1.0 million b/d in 2026, before reducing strategic builds in 2027.”

But given the lack of transparency around the stockpiles, it is impossible to forecast purchasing behaviour with a high degree of confidence.

Other than in time of war, the conditions under which China might release oil from commercial and especially strategic stocks are also obscure.

China has a long tradition of actively employing state-owned reserves of food to manage prices and dampen fluctuations as well as relieving outright shortages. More recently, strategic reserve managers have purchased materials including aluminium and copper to support domestic producers and prices in periods of excess supply, before releasing them later when prices have risen.

But the conditions (if any) under which China would release oil from strategic stocks in response to high prices and shortages other than in a conflict remain unknown.

CONCLUDING OBSERVATIONS

China’s reliance on imported crude most of it arriving along sea lanes patrolled by the U.S. Navy and its allies has been identified by the government as one of the top threats to national security. China’s economy and its warfighting ability would both be vulnerable to sanctions or an embargo in the event of a future conflict with the United States over Taiwan.

Like other import-dependent countries, China’s government has responded by accumulating strategic inventories, as well as encouraging greater fuel efficiency, oil substitutes and more domestic production.

China’s inventories are still rising, but are currently equivalent to slightly more than three months of net imports, which is comparable to stocks planned by other import-dependent countries over the last century.

China treats inventory levels as a national security matter and a state secret, which is understandable given the country’s extreme vulnerability. But the lack of transparency encourages suspicion and speculation about the country’s military planning for future conflicts.

Lack of transparency has also become the single most important source of uncertainty in forecasting future production, consumption, inventory and price balances in the global oil market.