Authored by Nick Cunningham via OilPrice.com,

In the long-term, many oil analysts expect the world to become increasingly dependent on oil production from the Middle East, as U.S. shale fades in importance.

However, geopolitical turmoil is already causing disruptions in major oil-producing countries in the Middle East, raising questions about the region’s ability to supply the global market in the long run.

The IEA has repeatedly warned that while U.S. shale has led to oversupply in the short run, shale output cannot meet future demand by itself. By the mid-2020s, especially because there are questions about the longevity of U.S. shale, there could be a much greater reliance on the Middle East, just as there was in the past.

However, according to the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (OIES), the deteriorating geopolitical landscape in the Middle East could leave longstanding scars on the region’s energy sector.

Geopolitical threats are cropping up in various ways in the Middle East and North Africa. Formal institutions have been weakened, and in places like Libya, Yemen and Syria there is an absolute lack of legitimacy in government. Non-state actors have stepped into the void, such as Hezbollah, the Houthis, Libya Dawn, and others, according to OIES. These rivaling power centers make it tricky for oil companies and oilfield services to make investments.

As far as the oil market goes, these geopolitical problems are not obvious just yet. The glut of U.S. shale has inoculated the oil market from instability and unrest for the time being. Also, while there are plenty of sources of conflict and no shortage of potential threats, actual oil production outages have remained minimal. In fact, Iran ramped up production after the removal of international sanctions, while Libya, and Nigeria restored quite a bit of output after serious outages.

Nevertheless, geopolitical flashpoints are sowing the seeds of future supply problems, OIES argues. For instance, as tension bubbles, Middle Eastern governments are stepping up spending on security and defense, and the ballooning expenditures translate into higher revenue requirements. That means that a lot of key oil producers will need higher oil prices for their budgets to breakeven.

Moreover, geopolitical tension today is preventing the necessary investments in new production capacity. For example, while Iran was able to restore huge volumes of upstream production after the lifting of sanctions, the Trump administration seems set on ratcheting up tensions. It is unclear where this conflict is heading, but it is already deterring investment in oil and gas production capacity in Iran. French oil company Total is trying to invest in the South Pars Phase 2 project, but has suggested it might hesitate if U.S. sanctions returned.

Meanwhile, tension elsewhere has also inhibited investment in production capacity. For years, the Kurdish Regional Government has tried to attract upstream investment, but the conflict with the central government in Baghdad will prevent the region from scaling up output.

OIES also cites the case of Libya, where unrest is not only leading to the occasional outage today, but it essentially prevents the country from realizing its full potential. OIES pointed out that in a 2005 forecast, the IEA predicted Libya would ramp up output to 3 million barrels per day by 2030. That seems unrealistic at this point, and Libya’s production is down from its pre-war level of 1.6 million barrels per day (mb/d) and is now stuck at around 1 mb/d.

While this may not seem like an acute problem today, geopolitical instability becomes increasingly problematic as the oil market tightens. Already, the cushion of crude inventories has been significantly reduced. Any unexpected outage becomes more influential in a tighter market.

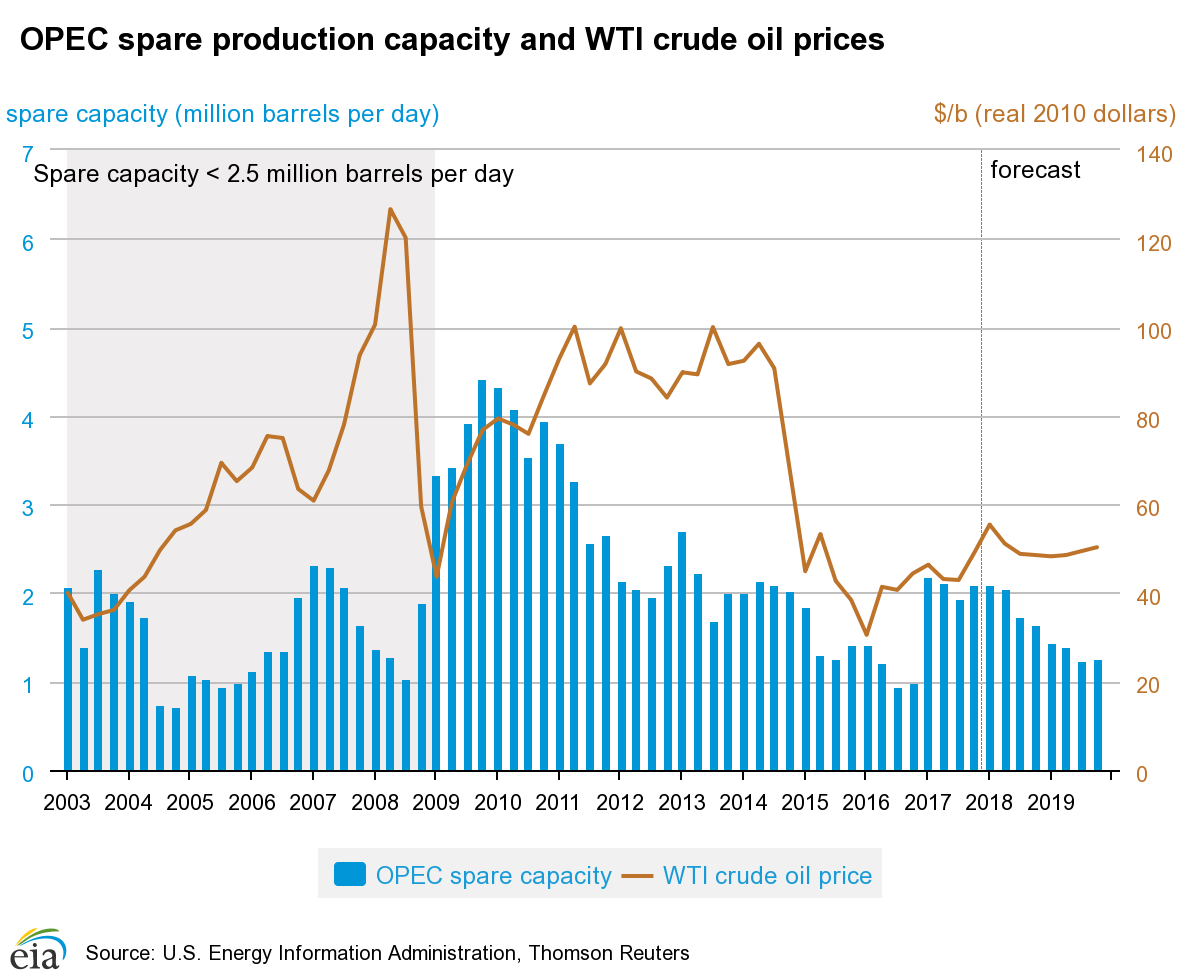

That is especially true because spare capacity is already thin, sitting at about 2 million barrels per day, which is at the low end historically. But spare capacity will shrink further once OPEC unwinds the current production cuts. As the oil market tightens, and absorbs new OPEC production, the EIA predicts that global spare capacity will fall to about 1.24 mb/d by the third quarter of 2019, an extremely low level.

As the years pass and demand rises, the global market will need more OPEC production. But as OIES argues, geopolitical turmoil today could prevent the group from bringing new supply online in the future.

In the near-term, the oil market will be well supplied with rising shale output and the prospect of the return of OPEC production.

(Click to enlarge)

But there are some serious questions about supply problems in the long-term.

via Zero Hedge http://ift.tt/2GQ9yYa Tyler Durden