The stakes are rising for the Maduro regime, and new U.S. sanctions on the Venezuela’s oil industry may be the point of no return for the country’s troubled leader…

Things have certainly moved into a higher gear in Venezuela, with a genuine diarchy vying for control over the country’s resources and populace. The alleged smuggling of gold reserves, politicized humanitarian aid, rampant disinformation against the background of all-encompassing poverty and deprivation – Venezuela of 2019 bears an uncanny likeness to any stereotypical conflict-ridden Latin American country of the 20th century.

The US sanctions announced January 28 have driven a wedge between PDVSA and the United States, creating a point of no return for President Maduro. There is still no 100 percent certainty that Maduro will be ousted and if he manages to stay (through which, given his political skills and occasional antics, would be tantamount to a miracle), Venezuela could rethink its oil strategy on a grand scale. Let’s, however, look at the developments in Venezuela piece by piece before we jump into any conclusions.

The most evident and palpable consequence of the US sanctions was the almost immediate cessation of activity with US Gulf Coast refiners. The US Treasury has stated that under President Maduro PDVSA has become a “vehicle for embezzlement and corruption” and hence from January 28 onwards all income from the sales of Venezuelan crude should be transferred to escrow accounts in the United States, accessible only by the Guiadó government. Given that PDVSA has been a vehicle for embezzlement every single year of its 43-year old history, it is remarkably naive to believe a transfer of control from Maduro to Guaidó would bring about any structural shift, however, the severeness of the punishment brings across a powerful political message – a message that US refiners cannot shrug off easily.

Statistically, every day two cargoes of Venezuelan crude were being loaded in its ports and setting sail towards market outlets. The odds were that one of these two cargoes is destined for the US market – roughly 44 percent of Venezuelan exports went to American customers in 2018. The initial shipping numbers might bring you a smaller percentage, yet keep in mind that Aruba, Curacao and the Dutch Caribbean islands worked as transshipment hubs towards America for PDVSA. Absent a swift removal of Maduro from office, all of that will be gone after April 28 when the 3-month winding down period for cutting all ties with PDVSA comes to an end. It is difficult not to understate the importance of the US market to Venezuela – as opposed to dealings with China and Russia (where PDVSA was paying back advance payments by the medium of oil), exports to US provided one of the rare opportunities to receive much-needed hard currency, an estimated $1 billion per month.

Given that Venezuela has defaulted on more than $60 billion worth of bond issuances (the only bond that is still intact is the PDVSA 2020 bond), such a lifeline of dollars will be sorely missed. However, it has to be stated that Venezuelan supplies were essential to US Gulf Coast refiners, too.

Despite all the public bravado, refiners will have a hard time replacing Venezuelan volumes with grades of equivalent quality and, most importantly, similar price level. Valero Energy, taking in approximately 90kbpd of Venezuelan crude in Q4 2018, stated it will replace them with Canadian volumes, pretty much the only heavy sour stream that demonstrates healthy USGC coking margins. Yet as we have determined in our previous weekly columns, Canada is struggling to market all of its produced crude (which is not helped by the mandated Alberta production cuts) and will remain to do so until new pipeline capacity and rail tank car additions hit the market in late 2019. There is a high probability that the price of Canadian crudes will increase on the back of USGC refiners’ interest, pushing the margins further down.

Valero’s future travails pale in comparison with those of Citgo, which has become a proxy battlefield between Venezuela’s two rival leaders. First Maduro has ordered all Venezuelan Citgo employees to return home, then Guaidó has urged them to stay where they are, thus now no one really knows what to do. Citgo will become a litmus test of Guaidó’s political prowess – dealing with Venezuelan authorities with the backing of a hawkish US Administration is one thing, finding a compromise with Russian state-owned (and may I add, US-sanctioned) oil company Rosneft is an entirely different one. Citgo’s minority 49.9 percent stake was pledged by Maduro to Rosneft as collateral in return for a 1.5 billion loan provided in 2016, following which the Russian company immediately filed a lien with the Delaware Department of State asserting its right to own those 49.9 percent in case PDVSA defaults.

Guaidó has asserted that both China and Russia would be better off with him in power, pledging to respect the investments both Beijing and Moscow have made in Venezuela. Antagonizing Rosneft would be an unwise thing to do as it effectively operates the 150 kbpd Petromonagas crude upgrader facility, one of three working across the country capable of converting bituminous Orinoco crude into exportable volumes, and has stakes in five upstream projects (Petrovictoria, Petromonagas, Petromiranda, Petroperija, Boqueron). Chevron operates the 210kbpd Petropiar upgrader and envisages that it can keep up the stable operation despite all the political tension. The third upgrader, the 190kbpd Petrocedeno operated jointly by Total, Equinor and PDVSA, was expected to undergo a major maintenance program this quarter, however, seems to be working thus far.

Perhaps a bit wrongly, most of media attention was directed at the trading consequences of US sanctions, even though the most dramatic ramifications will be witnessed in Venezuela’s upstream sector. According to Platts estimates, up to 300kbpd of Venezuelan production might be out of operation amid an all-encompassing dearth of diluent, traditionally used to render the bituminous Orinoco crude transportable. Citgo was heretofore the major supplier of diluent, with some 120kbpd worth of exports effectively barred by the White House to sail to Venezuela under current circumstances. Reliance (having loaded two 2MMBbl VLCCs over the past few days – MT Folegandros I and MT Baghdad), having previously supplied 65kbpd, will most likely cease diluent supplies before April 28 so as not to put its US subsidiary RIL in the line of fire.

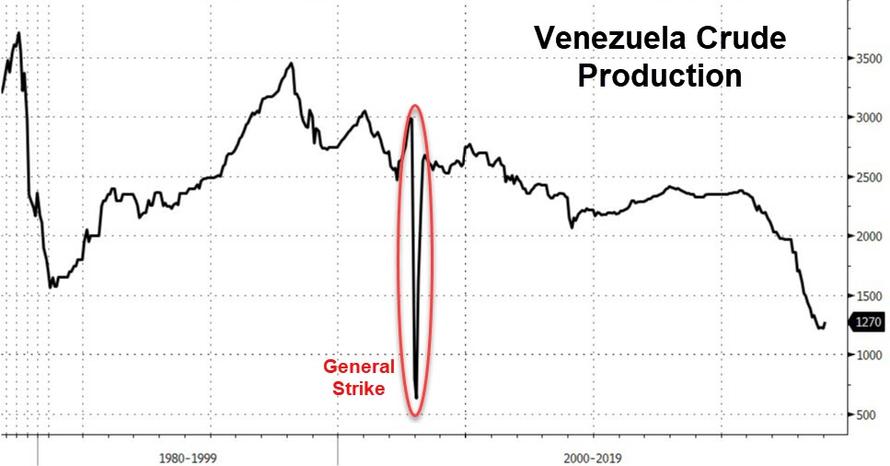

With minimal or no diluent to render its crude palatable, the current Venezuelan leadership risks seeing its production fall below 1mbpd on a permanent basis.

Venezuelan Oil Production

Should Maduro retain his post for longer and reroute the majority of Venezuela’s exports from the US to Asia, he would still see his income shrink on the back of falling production. Output decreases would further exacerbate the fuel shortage in the country – if today Paraguana works at 20 percent of capacity, further out it might drop even lower. This only goes on to highlight the complexity of US sanctions, which, despite being applicable for US companies only, have effectively cut off every entity with some interest or equity in the United States (as can be attested by all of Europe stopping PDVSA bond trades). At the same time it goes on to demonstrate the double game behind the humanitarian aid effort – its possibility was floated only when the “bringing Maduro to ruin” strategy reached the endgame.

Oddly enough, the United States keep on (the optimist might say involuntarily) curbing the world’s heavy sour streams. First actively contributing to Venezuela’s production downfall from 2.1mbpd in Jan 2017 to 1.1mbpd in Jan 2019, then making away with 1mbpd of Iranian exports, and now seeming intent on bring Caracas’ exports even lower. This can be, of course, easily explained in political terms, yet ultimately it is the US refiner who bears the economic brunt – whatever replacement there is for Venezuelan crude, be it WCS or Ecuadorian Napo, comes in insufficient quantities and thus would most likely be overpriced.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2t9T1tj Tyler Durden