Almost Daily Grant’s, Submitted by Grant’s Interest Rate Observer

On Friday, the Nikkei Asian Review reports that Nomura Holdings, Inc. (8604 on the Tokyo Stock Exchange) expects to close over 30 of its 156 domestic retail branches, “previously considered a sacred cow by the group.” In addition, Nomura will eliminate roughly half of its 11 administrative departments and “revisit its policy of maintaining hubs in Japan, the U.S. and Europe.” That comes after the investment bank reported a ¥101.2 billion ($911 million) loss for the nine months ended Dec. 31, its worst such showing since 2008.

Nomura’s misadventures are no outlier. In early March, Mizuho Financial Group, Inc. was forced to take a ¥680 billion write down that included ¥150 billion worth of losses related to its portfolio of overseas bonds. More broadly, the Tokyo Stock Exchange Bank Index has seen its return on equity decline in each of the last five years, to 5.33% in 2018 from 9.77% in 2013. The index trades at a paltry 0.47 times book value, worse than even the EURO Stoxx Bank Index’s similarly-depressed 0.62 price-to-book ratio and far below the 1.18 times book valuation commanded by the U.S. KBW Bank Index.

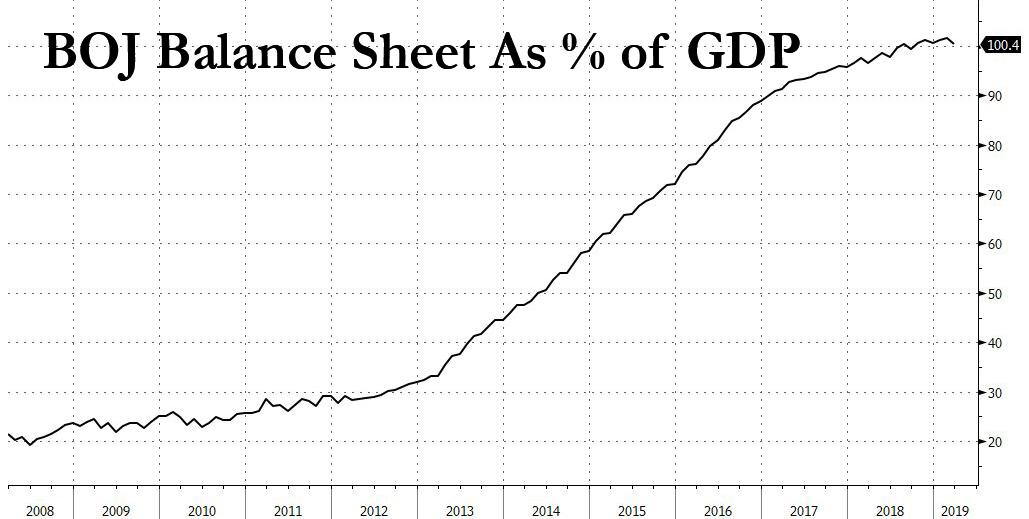

Of course, much like Europe, Japan’s macro-economic backdrop features negative interest rates and aggressive central bank asset purchases. The BoJ has accumulated ¥557 trillion in assets, equivalent to 101% of 2018 nominal GDP (that compares to about 39% in Europe and 19% in the U.S.), as policymakers continue to up the ante in their quest to achieve a 2% measured rate of inflation.

With its gargantuan portfolio, the BoJ wields substantial control of the country’s capital markets. As noted by the Financial Times on Sunday, the central bank now holds close to 80% of outstanding ETF assets, equating to approximately 5% of Japan’s total market capitalization, while data from Bloomberg pegs the BoJ ownership of the Japanese Government Bond Market at 43%.

Financial institutions are beginning to publicly balk at these monetary machinations. Last week, Makoto Takashima, president of Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corp. and chairman of the Japanese Bankers Association, told Bloomberg that the Bank of Japan must “carefully consider” the impact of deepening its subzero interest rate policy: “It will be a quite difficult decision to make. Simply speaking, that would cause policy side-effects to further grow.” Back on March 3, Mizuho Bank, Ltd. CEO Koji Fujiwara expressed similar reservations over any escalation of Japan’s radical monetary policy: “I think the BoJ’s actions so far have been beneficial, but I think the time has come to look carefully at the negative side effects and reconsider.”

For his part, BoJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda opined in March that “I don’t think our ETF buying is having any effect on market function.” The central banker said in a speech today that the BoJ “needs to continue easing persistently.” Of Japan’s banks, Kuroda attributed their profit woes to “structural factors, such as a dwindling population,” while pledging vigilance “to the risk [these structural factors] could erode [banks’] capital base and have a negative impact on financial intermediation.”

With BoJ policy already extreme by most objective measures, Kuroda’s determination to maintain ultra-loose policies in the face of banking industry protests can be potentially explained by a speech at Oxford University on June 12, 2017. In that address, the BoJ governor articulated his plan to rouse the Land of the Rising Sun from its longstanding disinflationary torpor. Namely, manipulate expectations such that citizens begin to expect rising prices, which would then presage the real McCoy:

I took office as Governor of the Bank of Japan in March 2013 and immediately introduced a monetary policy regime — quantitative and qualitative monetary easing, (QQE) — that is quite different from past regimes. QQE consists of two pillars: (1) directly working on people’s expectations through a price stability target of 2 percent and a strong and clear commitment to doing whatever it takes to achieve this, and (2) directly encouraging a decline in long-term interest rates through large-scale purchases of long-term Japanese government bonds (JGBs).

In practice, QQE has produced its intended effects. Inflation expectations climbed notably after the introduction of QQE. This demonstrates that a strong determination by the central bank pushes up people’s forward-looking inflation expectations.

On that score, success remains elusive. According to a Bloomberg survey of 2,127 Japanese households conducted in February and March, half of respondents “have never heard of” Kuroda’s grand monetary stimulus, “the highest level since the question was introduced in September 2013.” Meanwhile, year-over-year CPI inflation has averaged 0.45% over the last 36 months.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2G5tvNl Tyler Durden