Authored by Lance Roberts via RealInvestmentAdvice.com,

Last week, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) published the March monthly “employment report” which showed an increase in employment of 196,000 jobs. As Mike Shedlock noted on Friday:

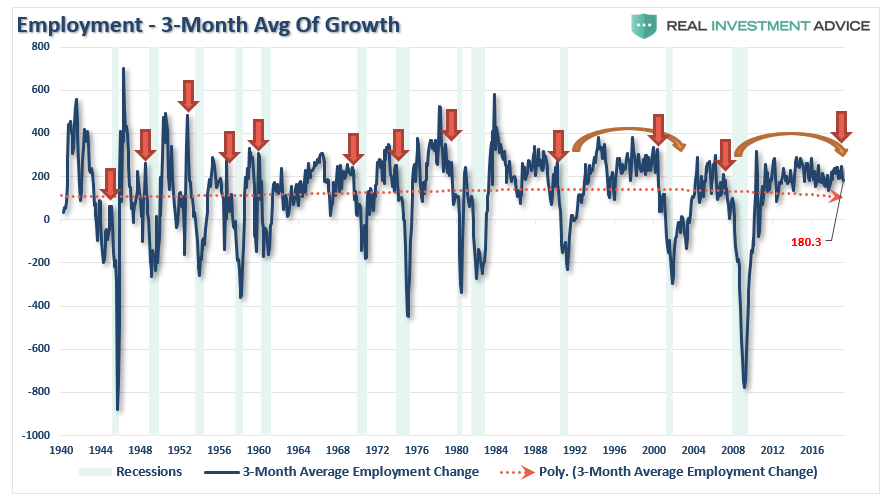

“The change in total non-farm payroll employment for January was revised up from +311,000 to +312,000, and the change for February was revised up from +20,000 to +33,000. With these revisions, employment gains in January and February combined were 14,000 more than previously reported. After revisions, job gains have averaged 180,000 per month over the last 3 months.

BLS Jobs Statistics at a Glance

-

Nonfarm Payroll: +196,000 – Establishment Survey

-

Employment: -201,000 – Household Survey

-

Unemployment: -24,000 – Household Survey

-

Involuntary Part-Time Work: +189,000 – Household Survey

-

Voluntary Part-Time Work: +144,000 – Household Survey

-

Baseline Unemployment Rate: Unchanged at 3.8% – Household Survey

-

U-6 unemployment: Unchanged at 7.3% – Household Survey

-

Civilian Non-institutional Population: +145,000

-

Civilian Labor Force: -224,000 – Household Survey

-

Not in Labor Force: +369,000 – Household Survey

-

Participation Rate: -0.2 to 63.0– Household Survey”

There is little argument the streak of employment growth is quite phenomenal and comes amid hopes the economy will continue to avoid a recessionary contraction. When looking at the average rate of employment growth over the last 3-months, as Mike noted at 180,000, there is a clear slowing in the trend of employment. It is this “trend” we will examine more closely today.

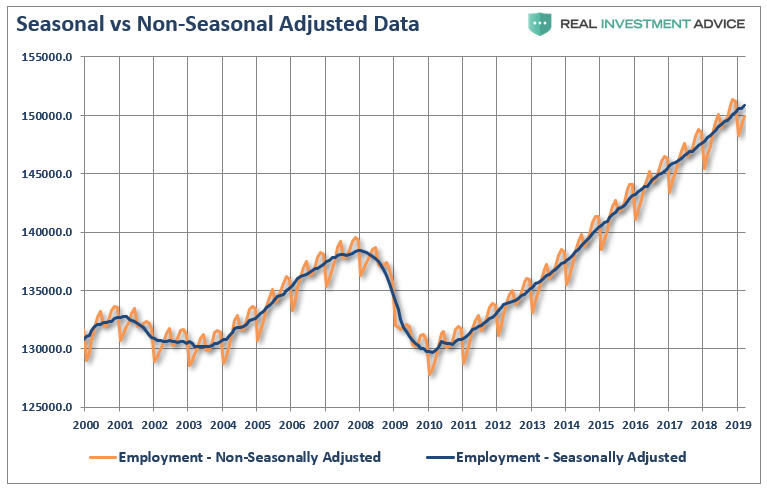

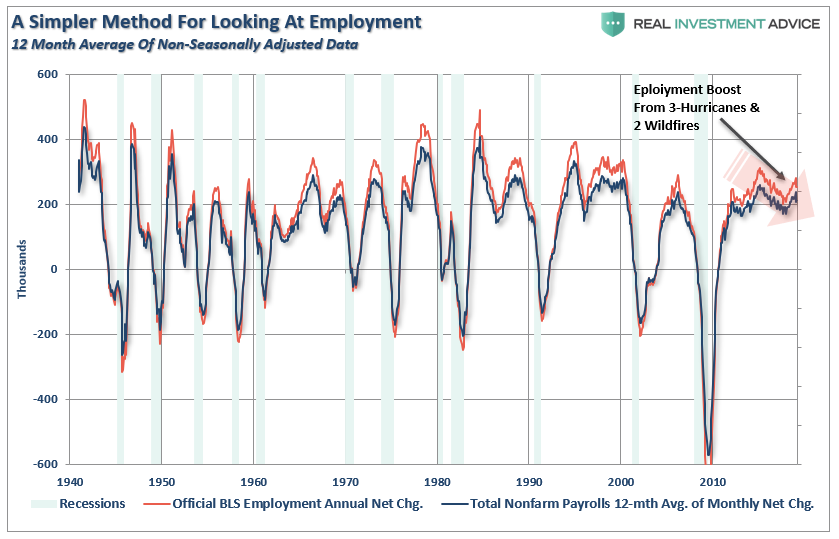

While a tremendous amount of attention is focused on the monthly employment numbers, the series is one of the most highly manipulated, guesstimated, and annually revised series produced by any agency. The whole issue of seasonal adjustments, which try to account for temporary changes to employment due to a variety of impacts, is entirely too systematic to be taken at face value. The chart below shows the swings between the non-seasonally adjusted and seasonally adjusted data – anything this rhythmic should be questioned rather than taken at face value as “fact.”

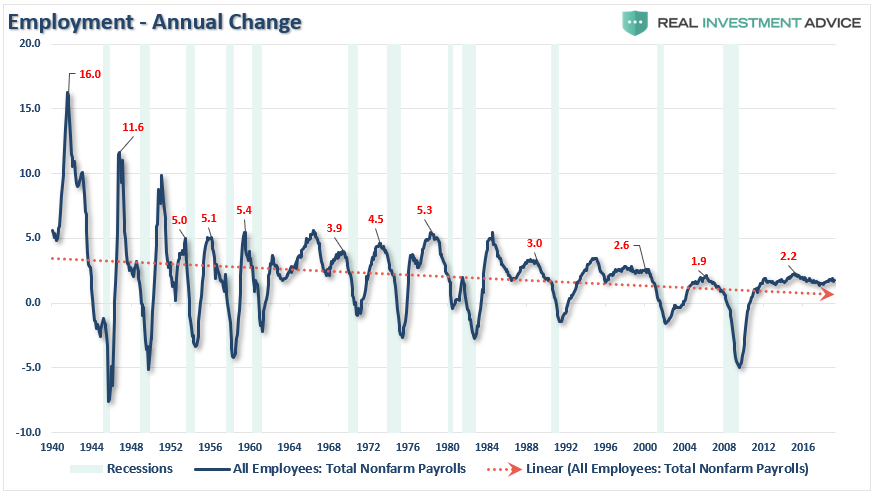

As stated, while most economists focus at employment data from one month to the next for clues as to the strength of the economy, it is the “trend” of the data which is far more important to understand.

The chart below shows the peak annual rate of change for employment before the onset of a recession. The current annual rate of employment growth is 1.4% which is lower than any previous employment level prior to a recession in history.

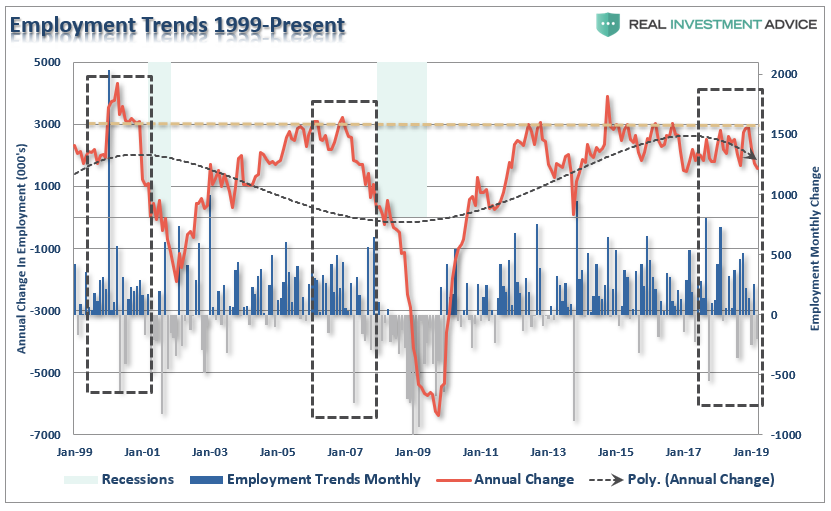

But while this is a long-term view of the trend of employment in the U.S., what about right now? The chart below shows employment from 1999 to present.

While the recent employment report was slightly above expectations, the annual rate of growth is slowing. The chart above shows two things. The first is the trend of the household employment survey on an annualized basis. Secondly, while the seasonally-adjusted reported showed 196,000 jobs created, the actual household survey showed a loss of 200,000 jobs.

Many do not like the household survey for a variety of reasons but even if we use the 3-month average of seasonally-adjusted employment we see the same picture. (The 3-month average simply smooths out some of the volatility.)

But here is something else to consider.

While the BLS continually adjusts and fiddles with the data to mathematically adjust for seasonal variations, the purpose of the entire process is to smooth volatile monthly data into a more normalized trend. The problem, of course, with manipulating data through mathematical adjustments, revisions, and tweaks, is the risk of contamination of bias. A simpler method to use for smoothing volatile monthly data is using a 12-month moving average of the raw data as shown below.

Notice that near peaks of employment cycles the employment data deviates from the 12-month average but tends to reconnect as reality emerges. (Also, note the pickup in employment due to the slate of “natural disasters” in late 2017 which are now fading as reconstruction completes)

Sometimes, “simpler” gives us a better understanding of the data.

Importantly, there is one aspect to all the charts above which remains constant. No matter how you choose to look at the data, peaks in employment growth occur prior to economic contractions rather than an acceleration of growth.

However, there is more to this story.

A Function Of Population

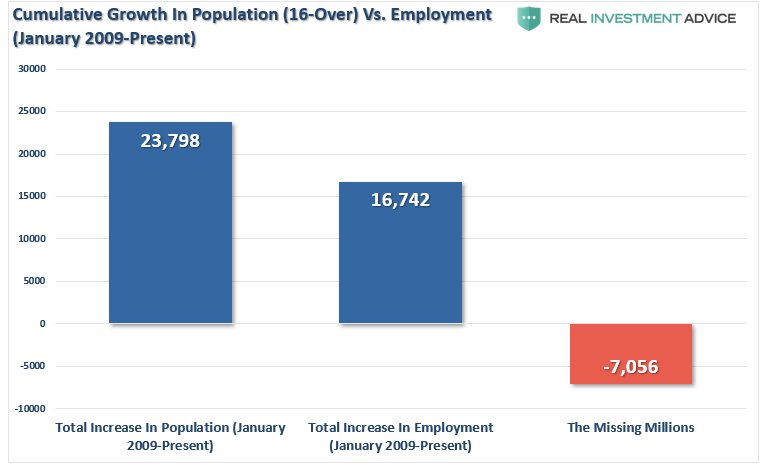

One thing which is never discussed when reporting on employment is the “growth” of the working age population. Each month, new entrants into the population create “demand” through their additional consumption. Employment should increase to accommodate the increased demand from more participants in the economy. Either that or companies resort to automation, off-shoring, etc. to increase rates of production without increases in labor costs. The chart below shows the total increase in employment versus the growth of the working age population.

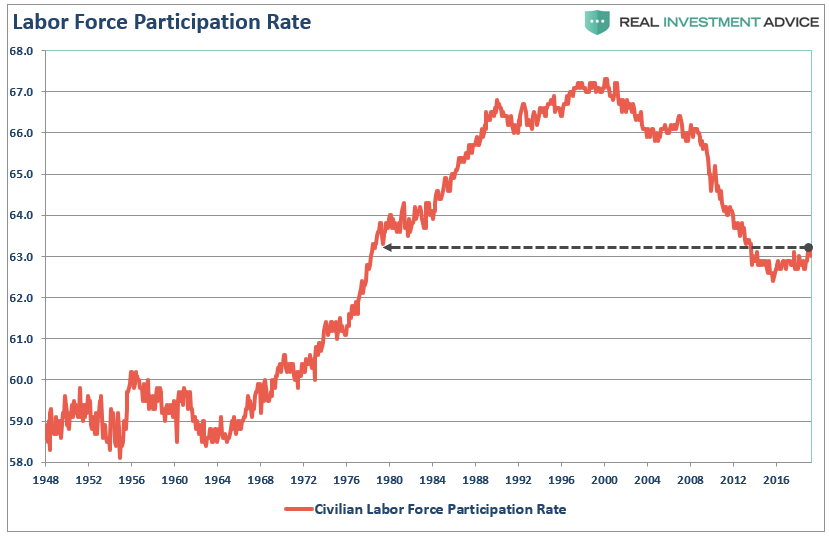

The missing “millions” shown in the chart above is one of the “great mysteries” about one of the longest economic booms in U.S. history. This is particularly a conundrum when the Federal Reserve talks about the economy nearing “full employment.” The Labor Force Participation Rate below shows this great mystery.

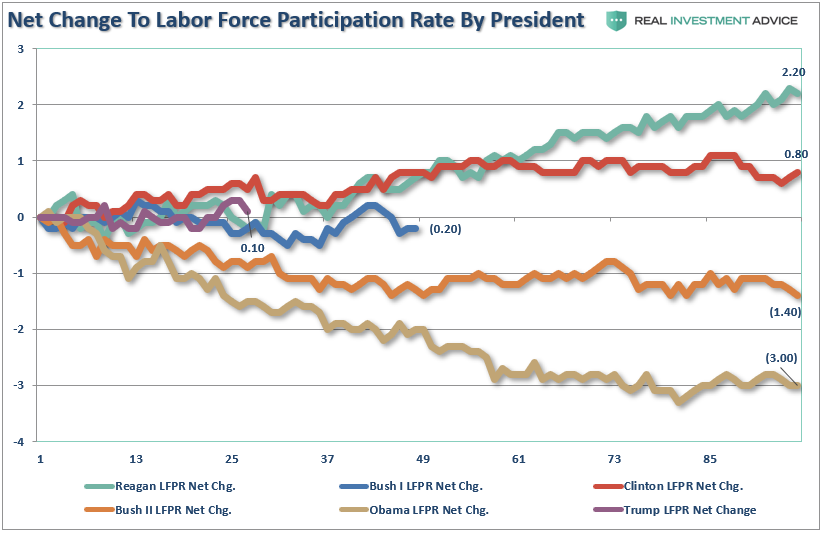

Since many conservatives continue to credit President Trump with a booming economy and employment gains, we can look at changes to the labor force participation rate by President as a measure of success. Currently, Trump’s gains are either less than Clinton, the same as Reagan, or tracking Bush Sr.; “spin it” as you will.

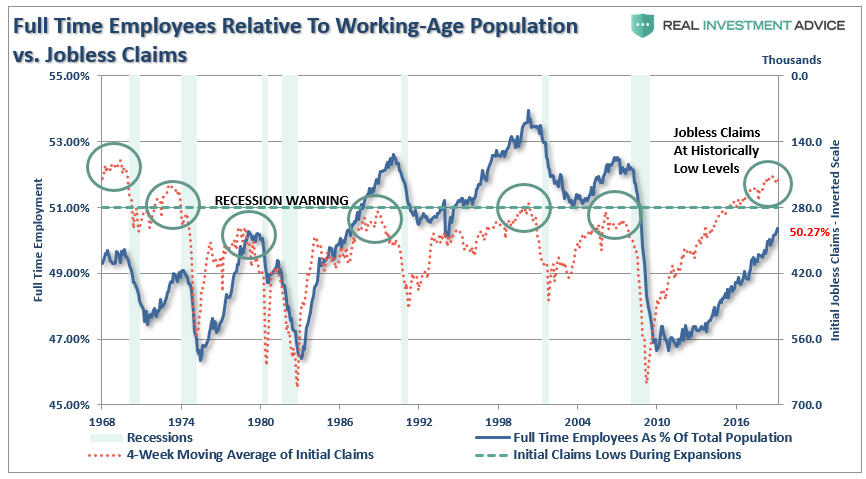

Of course, as we are all very aware, there are many people who are working part-time, going to school, etc. But even when we consider just those working “full-time” jobs, particularly when jobless claims are reaching record lows, the percentage of full-time employees is still well below levels of the last 35 years.

“With jobless claims at historic lows, and the unemployment rate at 4%, then why is full-time employment relative to the working-age population at just 50.27% which is down from 50.5% last month?”

It’s All The Baby Boomers Retiring

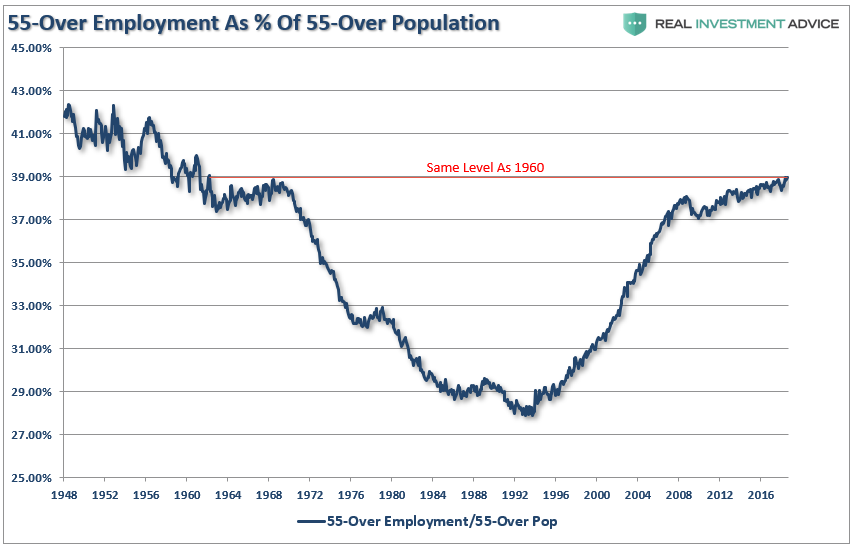

One of the arguments often given for the low labor force participation rate is that millions of “baby boomers” are leaving the workforce for retirement. This argument doesn’t carry much weight given that the “Millennial” generation, which is significantly larger, is simultaneously entering the workforce. The other problem is shown below, there are more individuals over the age of 55, as a percentage of that age group, in the workforce today than in the last 50-years.

Of course, the reason they aren’t retiring is that they can’t. After two massive bear markets, weak economic growth, questionable spending habits,and poor financial planning, more individuals over the age of 55 are still working because they simply can’t “afford” to retire.

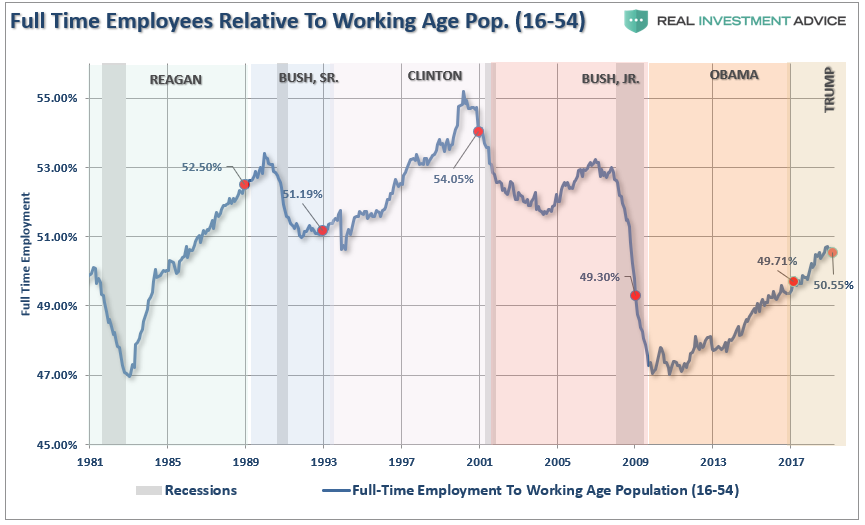

However, for argument sake, let’s assume that every worker over the age of 55 retires. If the “retiring” argument is valid, then employment participation rates should soar once that group is removed. The chart below is full-time employment relative to the working-age population of 16-54.

Importantly, note in the first chart above the number of workers over the age of 55 increased last month. However, employment of 16-54 year olds declined from 50.78% to 50.55%. It is also, the lowest rate since 1985, which was the last time employment was increasing from such low levels.

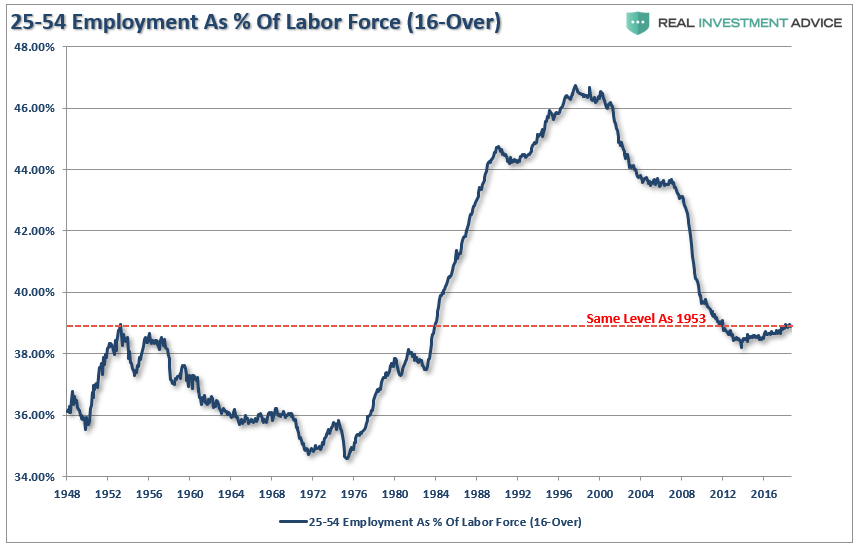

The other argument is that Millennials are going to school longer than before so they aren’t working either. (We have an excuse for everything these days.) The chart below strips out those of college age (16-24) and those over the age of 55. Uhm…

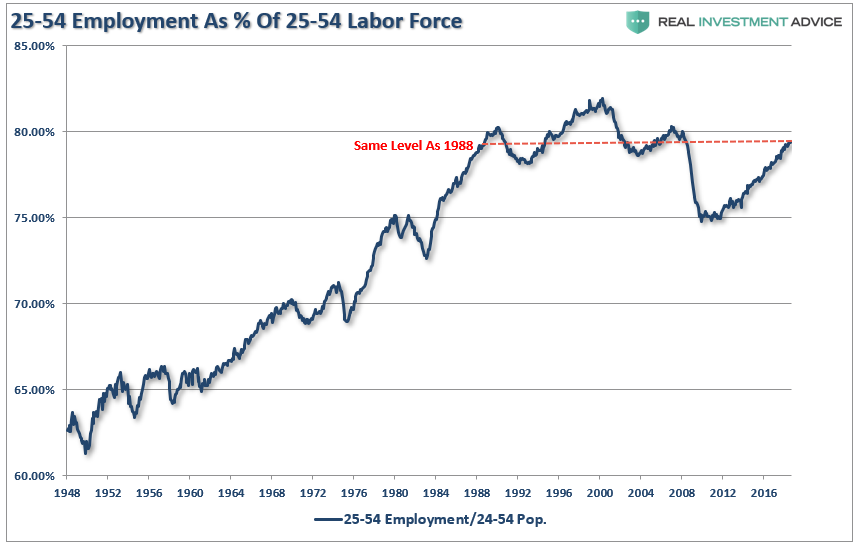

Here is the same chart of employed 25-54 year olds as a percentage of just that group.

When refined down to this level, talk about data mining, we do actually see recovery, however, after the longest economic expansion on record, a record stock market, and record levels of corporate debt to fund expansions and buybacks; employment ratios for this group are at the same level as seen in 1988. Such should raise the question of just how robust the labor market actually is?

Low initial jobless claims coupled with the historically low unemployment rate are leading many economists to warn of tight labor markets and impending wage inflation. If there is no one to hire, employees have more negotiating leverage according to prevalent theory. While this seems reasonable on its face, further analysis into the employment data suggests these conclusions are not so straightforward.

Strong Labor Statistics

Michael Lebowitz recently pointed out some important considerations in this regard.

“The data certainly suggests that the job market is on fire. While we would like nothing more than to agree, there is other employment data which contradicts that premise.”

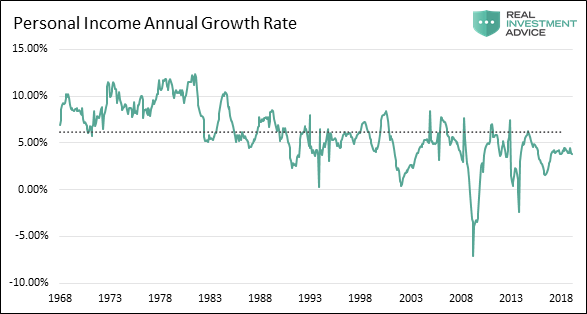

For example, if there are indeed very few workers in need of a job, then current workers should have pricing leverage over their employers. This does not seem to be the case as shown in the graph of personal income below.

Furthermore, a closer inspection of the BLS data reveals that, since 2008, 16 million people were reclassified as “leaving the workforce”. To put those 16 million people into context, from 1985 to 2008, a period almost three times longer than the post-crisis recovery, a similar number of people left the workforce.

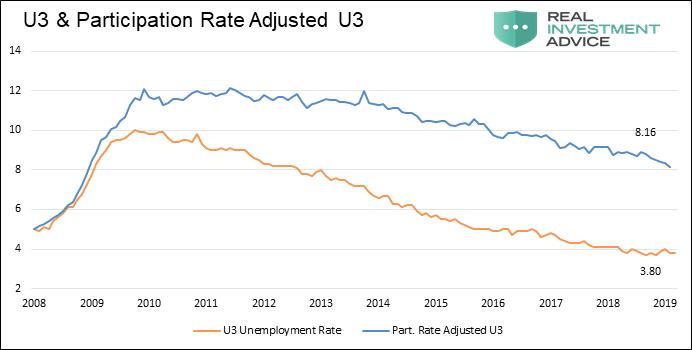

Why are so many people struggling to find a job and terminating their search if, as we are repeatedly told, the labor market is so healthy? To explain the juxtaposition of the low jobless claims number and unemployment rate with the low participation rate and weak wage growth, a calculation of the participation rate adjusted unemployment rate is revealing.

When people stop looking for a job, they are still unemployed, but they are not included in the U-3 unemployment calculation. If we include those who quit looking for work in the data, the employment situation is quite different. The graph below compares the U-3 unemployment rate to one that assumes a constant participation rate from 2008 to today. Contrary to the U-3 unemployment rate of 3.90%, this metric implies an adjusted unemployment rate of 8.69%.

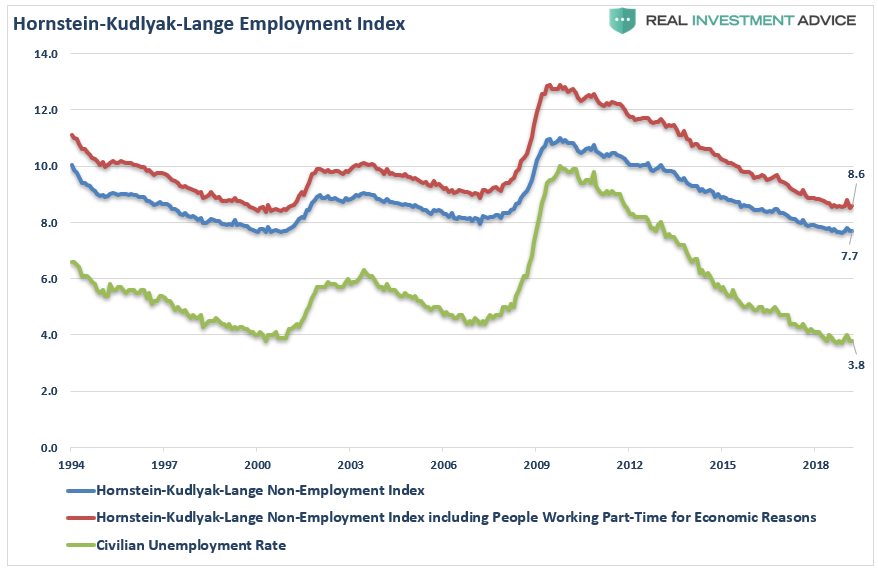

Importantly, this number is much more consistent with the data we have laid out above, supports the reasoning behind lower wage growth, and is further confirmed by the Hornstein-Kudlyak-Lange Employment Index.

(The Hornstein-Kudlyak-Lange Non-Employment Index including People Working Part-Time for Economic Reasons (NEI+PTER) is a weighted average of all non-employed people and people working part-time for economic reasons expressed as the share of the civilian non-institutionalized population 16 years and older. The weights take into account persistent differences in each group’s likelihood of transitioning back into employment. Because the NEI is more comprehensive and includes tailored weights of non-employed individuals, it arguably provides a more accurate reading of labor market conditions than the standard unemployment rate.)

One of the main factors driving the Federal Reserve to raise interest rates and reduce its balance sheet is the perceived low level of unemployment. Simultaneously, multiple comments from Fed officials suggest they are justifiably confused by some of the signals emanating from the jobs data. As we have argued in the past, the current monetary policy experiment has short-circuited the economy’s traditional traffic signals. None of these signals is more important than employment.

As Michael noted:

“Logic and evidence argue that, despite the self-congratulations of central bankers, good wage-paying jobs are not as plentiful as advertised and the embedded risks in the economy are higher. We must consider the effects that these sequences of policy error might have on the economy – one where growth remains anemic and jobs deceptively elusive.

Given that wages translate directly to personal consumption, a reliable interpretation of employment data has never been more important. Oddly enough, it appears as though that interpretation has never been more misleading. If we are correct that employment is weak, then future rate hikes and the planned reduction in the Fed’s balance sheet will begin to reveal this weakness soon.”

As an aside, it is worth noting that in November of 1969 jobless claims stood at 211,000, having risen slightly from the lows recorded earlier that year. Despite the low number of claims, a recession started a month later, and jobless claims would nearly double within six months. This episode serves as a reminder that every recession followed interim lows in jobless claims and the unemployment rate. We are confident that the dynamics leading to the next recession will not be any different.

But then again, maybe the yield-curve is already giving us the answer.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2OUaWya Tyler Durden