With the goal of increasing Oxford University’s undergraduate students intake from disadvantaged backgrounds from 15% to 25% over the next four years, the prestigious British university has unveiled a “sea change” in its admissions process.

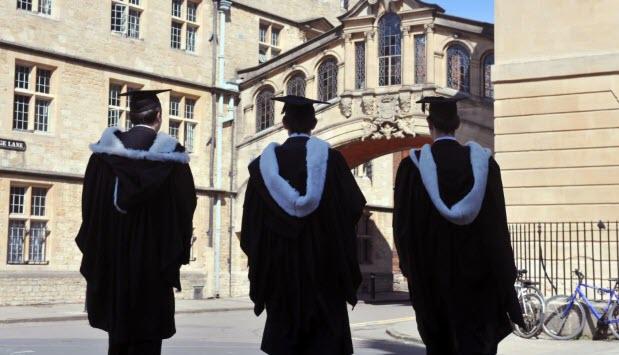

Echoing the new SAT ‘Adversity Score’ in the US, which attempts – through various socioeconomic factors – to adjust applicants’ ‘clean’ merit score for their relative disadvantage in life, The Telegraph reports that Oxford will offer places with lower grades to students from disadvantaged backgrounds for the first time in its 900-year history.

50 students in the new intake – which will include refugees and young carers – will be eligible to receive offers “made on the basis of lower contextual A-level grades, rather than the university’s standard offers”.

Additionally, the University revealed that it will launch two new programmes, entitled Opportunity Oxford and Foundation Oxford, in a bid to boost diversity.

-

Foundation Oxford will be open to 50 students with “high academic potential” who have personally experienced particularly severe disadvantage or educational disruption – as well as refugees and carers – and will last for a year. Students will have to pass the ‘Foundation’ year before being admitted to their undergraduate course.

-

Meanwhile, Opportunity Oxford will run for two weeks and is aimed at 200 students from more disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds who are on track for the required grades, but who “need additional support to transition successfully from school to Oxford”.

So, what counts as disadvantaged?

The BBC reports that it is not by income thresholds or ethnicity, but is mainly based on a socio-economic profile of where people live, which sounds very similar to the Adversity Score.

This uses two postcode-based systems, called Polar and Acorn, which measure local levels of deprivation or affluence.

The particular focus of Polar is the level of entry to university from people living in that area.

There have been critics of Polar – including Universities Minister Chris Skidmore, who wants to find a better way of showing disadvantage.

For instance, a very poor area with relatively high levels of university entry, such as in some parts of London, might not appear to be disadvantaged.

But the university says it will also consider some individual markers of hardship – such as spending time in care or eligibility for free school meals.

Such approaches depend on helping people who have already tried for a place at Oxford.

These efforts by the university come after Labour MP David Lammy became embroiled in a Twitter row with Oxford University after he dubbed the institution “a bastion of white, middle class, southern privilege”. Additionally, Sutton Trust social mobility charity showed recently that Oxford and Cambridge recruit more students from eight, mostly-private schools than almost 3,000 other UK state schools put together.

However, the diversity drive has sparked frustration among some in the education sector.

As The BBC points out, if 25% of places are to be targeted at applicants from poorer areas – and in recent years, about 40% of places have gone to pupils from private schools – then that leaves 35% for everyone else. That would be the remaining slice of places for all those state school pupils who do not live in the most deprived areas – which is to say, state-educated families in the middle.

Dr Anthony Wallersteiner, head of Stowe School in Buckinghamshire, said that the number of privately-educated children getting places at Oxbridge had been “driven down” as part of efforts to boost diversity.

He recently told The Times that private-school parents claimed that their children were being “edged out” by social engineering.

Telegraph columnist Allison Pearson, who read law at Oxford, writes that she was from a “disadvantaged background.” And she would not have wanted adversity points to help her get into Oxford:

If someone had told me that the college only admitted me because of “contextual data” – my family’s low income, the paucity of books in our house, the fact I was from a broken home, or because, in my touching ignorance, I thought a Reader’s Digestcondensed version of Jonathan Livingston Seagull was a literary masterpiece (bless!), I would have been mortified.

I wouldn’t have wanted to be patronised in that way. If I wasn’t good enough to be admitted on my own merits to a university renowned for its excellence, then I’d rather not have gone to Oxbridge at all.

Pearson explains how the new policy came about:

The trouble starts when well-meaning, guilt-stricken liberals (that’s pretty much all university lecturers) start lowering the bar because too many comprehensives are bad at helping the brightest pupils to reach their full potential. (And too many teachers are Corbynists who detest Oxbridge anyway.)

Consider this perverse logic: those class warriors who are keenest on social mobility are also violently opposed to grammar schools, the greatest-known engine of social mobility, which give poorer children a high-class academic education that enables them to compete on a level playing field with their more privileged counterparts.

As IWF concludes, if adversity points become the norm, we will truly live in a post-merit world.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2EyT8EO Tyler Durden