Authored by Jeffrey Snider via Alhambra Investments,

Spitballing In German

Something just doesn’t smell right. As I’ve pointed out over the past few weeks, bill yields have been falling. The front, the 4-week instrument, has seen its equivalent rate plummet. This is consistent with deep liquidity problems as well as looming rate cuts (the two do go hand-in-hand).

Over the past two session, including today, however, bill yields have spiked. No rate cuts, problem solved? Hardly. Bill markets aren’t supposed to behave this way – in either direction. What you see below are positions getting crushed, people taken out on stretchers (to repurpose an old euphemism) for reasons that have nothing directly to do with T-bills.

What follows is more pure speculation on my part, so if that’s not your interest then this mess in bills is already enough to keep anyone busy wondering. Otherwise, I can’t help but figure about that one German bank whose name keeps popping up at these sorts of moments.

The fact that Deutsche Bank is still upright at all might seem evidence to the contrary; in other words, it’s been called a “troubled” bank for many years and no major systemic consequences to this point.

The real problem, in my hypothetical view, is that no one has as yet properly defined “troubled.” For much of those prior years, up until early 2017, DB was obviously in trouble with the US government. Some untoward behavior during the last housing bubble.

After they paid a big fine for it, the matter like the bank was forgotten during globally synchronized growth. And that’s ultimately what grabs my attention – DB’s time on the front pages coincides with eurodollar squeezes. The current one included; including the intensity of Euro$ #4 so far.

I’ve been writing about DB for years. In October 2016, for example, while the DOJ fine was the only explanation put forward you could already tell it was much deeper than that. It’s all but forgotten now, superseded by more insanity, but this one behemoth had actually gotten caught cheating on its stress test – and authorities quite purposefully looked the other way!

As amazing in its deception as that was, the truly appalling nature of it was revealed by the jump in DB’s stock upon opening this week after publication of the affair. In other words, “speculators” (of the non-evil persuasion, apparently) were bidding up the bank because they saw it as an indication that the ECB would surely go to any lengths to rescue it if they were already willing to dilute (fake, in part) the test results meant to calm everyone down.

It’s another sign not just suggesting the twisted nature of central banking but that for Deutsche Bank there really might be something to all this if the European Central Bank would go this far in perhaps just the early stages.

As we know, ever since liquidity indications turned very serious later last year, German authorities in particular have been unusually keen to marry up DB with some other bank; any other bank, even one almost as “troubled.” Equally conspicuous is how no one seems willing to step up. It’s as if everyone else in the behemoth bank business, a disturbed industry itself, is unwilling to pay even a hugely discounted price for what used to be the crown jewel of Europe’s former paradigm.

Why?

A few clues have appeared once again – coincidentally over just the past few days. The Financial Times, among others, has reported DB is now considering a “bad bank.”

Deutsche Bank is preparing a deep overhaul of its trading operations including the creation of a so-called bad bank to hold tens of billions of euros of assets as chief executive Christian Sewing shifts Germany’s biggest lender away from investment banking…

Deutsche’s equity and rates trading businesses outside continental Europe will be severely shrunk or closed entirely as part of the revamp, although the final decision is pending, according to four people briefed on the plan. Managers are also set to unveil a new focus on transaction banking and private wealth management.

The proposed bad bank, which is known internally as the non-core asset unit, will comprise mainly of long-dated derivatives, the people said. [emphasis added]

Longer-dated derivatives being shrunk and disbanded outside continental Europe? Does that sound like to you what it sounds like to me?

Here’s what I wrote about it in May 2014:

In that framing, DB’s capital might look dangerous, particularly with its primary position as the largest derivatives trader in the world. As we know from bank earnings across the industry, fixed income has been an extreme sore spot and one of rising concern (derivative trading falls in here).

I do think that is part of the larger picture, but I don’t believe there is any imminent danger for the bank, with management panicking into an emergency dilution. Instead, I think this relates to the overall planned trajectory that has been altered by the events of the past year. That includes fixed income where banks derive(d) a majority of revenue and profitability.

Let me translate into English: the bank, seeking to reclaim former glory (read: profits), bet huge on global recovery. At the time, it had just completed a capital campaign and quite purposefully announced what it was going to do with it: get into the money dealing businesses almost everyone else was steadily, busily getting out of.

FICC and “bond trading”, call it “fixed income”, that’s a whole lot in derivatives.

-

If Bernanke/Yellen was going to be right about 2014, then it would pay off spectacularly. Big banking would be back in a big way with DB right at the front of the reborn franchise.

-

What if Bernanke/Yellen were wrong about 2014? What if Yellen/Powell were wrong about globally synchronized growth?

DB would be left holding a derivatives book chock full of bad bets; money dealers are not neutral players. They never, ever have been no matter in how many textbooks they are described this way.

And if DB were in such a state, that might account for the distinct lack of suitors as well as the apparent urgency among German state regulators. It could also explain the sudden (but not surprising) appearance of now a €50 billion (first estimate) “bad bank.”

Here’s the thing, though. Deutsche wasn’t all on its lonesome out on the limb of Bernanke’s recovery story. It had partners. There were others on the other side(s) of its trades. There are some substantial systemic considerations to its increasing questions.

In other places, I’ve compared the bank to AIG; not in how it will trigger another 2008-style meltdown. Rather, I believe its tentacles and even business lines were similarly laid out – especially what I imagine to be a clouded securities lending business (the thing that actually cost AIG its whole business) that in May 2014 bet on EM markets and global junk.

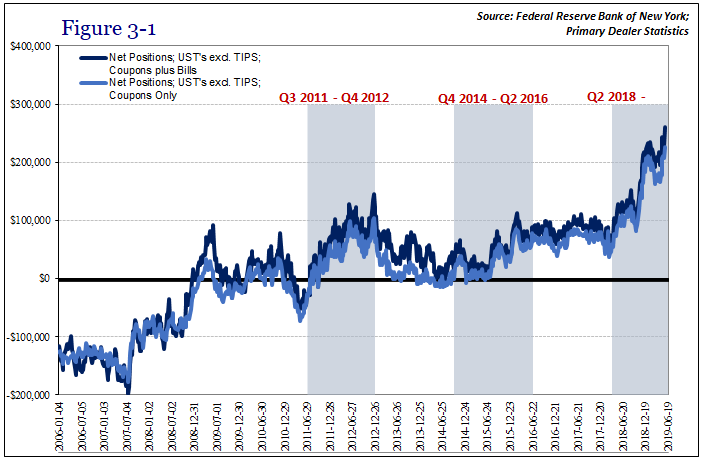

If DB was using its considerably lonely perch to create a collateral transformation monolith in the Eurobond as well as global repo and derivatives markets (UST’s are collateral in FX lending/borrowing, too), its reverse triggering a collateral crunch, this could explain a lot more than just DB (why there’s so much collateral urgency among primary dealers in Euro$ #4, for example, over and above what we’d already seen in Euro$ #2 and #3). Why German bunds, in particular, on May 29, 2018?

Unfortunately, this is a lot of speculating on my part. And I want to emphasize, and over-emphasize, the lack of direct evidence for it. It is at best a circumstantial theory. Take it with a huge grain of salt. Trying nothing more than to spitball what may (must?) be going on behind the scenes, how global dollar markets really seem to be almost afraid of something lurking in the shadows, but no longer very deep within them.

How does a July rate cut happen? The global economy further and significantly deteriorating would do the trick. So, too, would a surprise troubled bank surprisingly becoming more visibly troubled still.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2WLVTZH Tyler Durden