Authored by Mike Shedlock via MishTalk,

An alleged “Hatchet Job” by the NYT stirred up a hornet’s nest reaction from Tesla and EV lovers. Let’s reexamine.

Yesterday, I posted Electric Car Major Headache: Waiting Hours for Charging Bay then Hrs to Charge

My article contained excerpts from the New York Times article L.A. to Vegas and Back by Electric Car: 8 Hours Driving; 5 More Plugged In.

A furious reaction ensued.

1: EVs Superior in 3,000 Ways

2: Tesla Comparison – Reader Robjay

“What a skewed story! I own a one year old Tesla model 3 long range battery (325 miles). In one year I waited only once for 10 minutes to get a Tesla charger. Each Tesla supercharger station has at least 8 chargers. I will continue to pay $10.02, at the highest rate, to fully charge my 325 mile battery car. I will drive knowing I AM helping the environment. I will ENJOY a spectacular performing car with features no other car has, including SAFETY, as long as you adhere to proper driving .”

3: Hit Piece – Reader Davetech

“Yeah…so the original article by the NYT Reporter is what we would generally call a “Hit Piece”…designed to attempt to show things (EVs) in a bad light. MOST people drive (average commute) less than 35 miles per day ROUND TRIP. A better headline might be: “Gasoline powered car owners CAN’T charge at home…or at work…or at a destination charger… So gas car owners are FORCED to spend hours per year pulling into smelly gas stations and pumping gas, instead of a few seconds every night at home.”

4: Dumb Buyers – Reader Martin Archer

“Anyone so dumb that they drive a Bolt instead of a Tesla should be forced to wait even if a charger is available.”

5: Test of Time – Reader RWG

“As a Model 3 owner, we’ve done an 8,000 mile road trip from Oregon to Maryland and back again. No problems with the charging and with 310 mile range it’s nice to take a break every 3 to 5 hours. It was the most relaxing cross country drive we’ve done. Your opinions come across loud and clear but will not stand the test of time.”

6: Stop Hating the Future – Reader Carlos

“I recommend you stop hating a future that is coming even if you do not like it.”

Future is Coming

The curious thing about all of this is that I have commented repeatedly that electric cars own the future. I should have repeated the message.

I do not hate the future at all. But I cannot ignore the present.

Ownership Rates

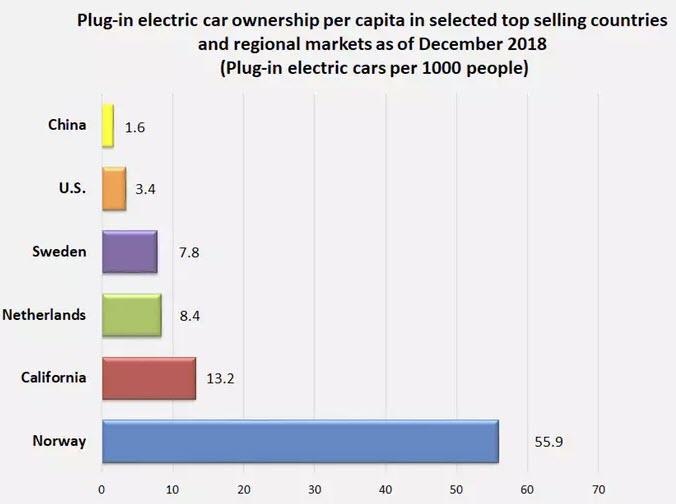

In the US, there are 3.4 Electric Cars Per 1,000 People.

Global cumulative sales of highway-legal light-duty plug-in vehicles reached 2 million units at the end of 2016,[1] 3 million in November 2017, and the 5 million milestone in December 2018. Sales of plug-in passenger cars achieved a 2.1% market share of new car sales in 2018, up from 1.3% in 2017, and 0.86% in 2016. The PEV market is shifting towards fully electric battery vehicles. The global ratio between BEVs and PHEVs went from 56:44 in 2012, to 60:40 in 2015, and rose to 69:31 in 2018.

As of December 2018, China had the largest stock of highway legal light-duty plug-ins with over 2 million domestically built passenger cars. China also dominates in plug-in electric bus deployment, with its stock reaching 343,500 units in 2016 out of global stock of about 345,000 vehicles. As of September 2018, the United States had one million plug-in cars, with California as the largest U.S. plug-in regional market with 537,208 plug-in cars sold up until December 2018. More than one million light-duty passenger plug-ins had been registered in Europe through June 2018, with Norway as the leading country with over 296,000 units registered by the end of 2018. Norway has the highest market penetration per capita in the world, and also has the world’s largest plug-in segment market share of new car sales, 49.1% in 2018. As of 2018, 10% of all passenger cars on Norwegian roads were plug-ins.

Math Test

3.4 vehicles per 1,000 people is a 0.34% ownership rate. And over half of that is from California which has extra incentive to make them affordable.

To be fair, the calculation is skewed to the low side because it includes a sizable number of people who are not old enough to drive, those who are disabled, etc.

We can improve upon that by looking at population groups.

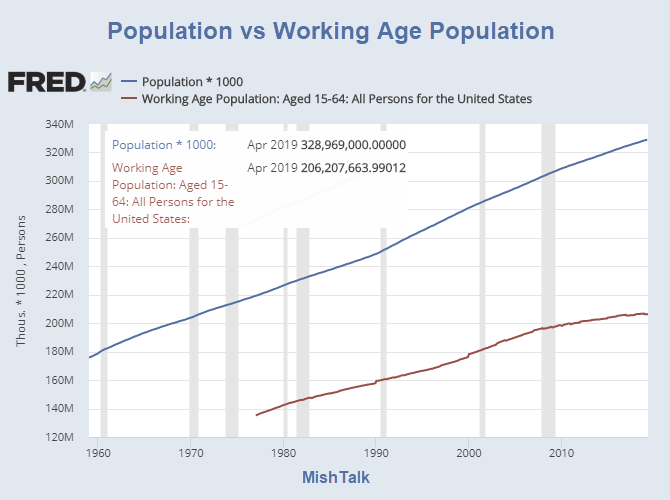

Population vs Working Age Population

There are about 329 million people in the US. Of that number, there are about 207 million aged 15-64.

207 million is thus a better starting point than 329 million as a potential car ownership age.

207/328 is 63% but a lot of people over the age of 64 still drive. 63% is on the low side.

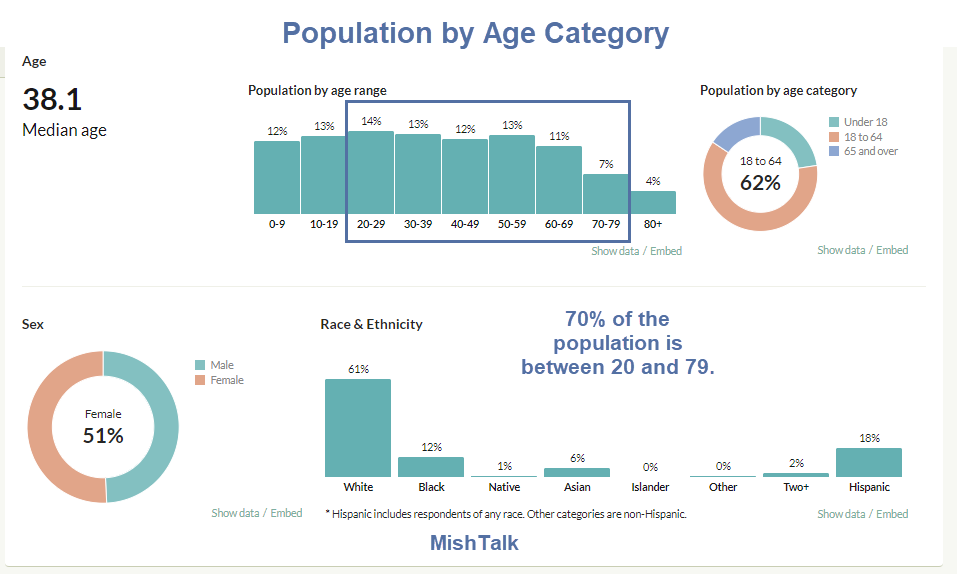

Population by Age Category

70% of the population is between 20 and 79. There are 18- and 19-year-olds who own cars, and some number of those over 79 tears old still driving.

70% of 329 million is 230 million.

After age 64, people might get away more easily with one car than two, but that is at least a very reasonable car ownership age range.

70% is probably on the high side.

A still better way to calculate ownership and EV percentage usage is to look at the number of licensed drivers.

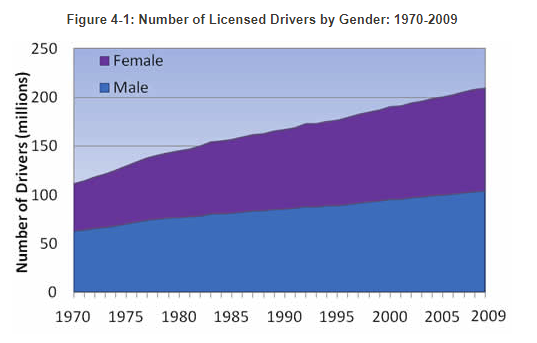

Licensed Drivers

“In 2009, 87 percent of the driving-age population (age 16 and over) have a license. There are 685 drivers for every 1,000 residents. In 1960, just a few years after all states required driver licensing, there were only 487 drivers for every 1,000 residents.”

All these numbers are similar but let’s use 685 drivers per 1,000 population as the best representation of what’s going on. The number conveniently lies between 63% and 70% so all the numbers realistically tie together.

Percentage of EVs Per Licensed Driver

In the US there are 3.4 plug-in electric cars per 685 licensed drivers.

(3.4 / 685) * 100 = 0.49%

A mere 0.49% of licensed drivers have a plug-in vehicle, and that includes hybrids!

In California, thanks to extra incentives, there are 13.2 plug-in electric cars per 685 licensed drivers. That percentage is a “whopping” 1.9%.

Basic Reality

If EVs were so damn superior, then usage would certainly top 0.49%.

Like it or not, the public does not believe EVs to be superior, taking price into consideration. There is no other possible conclusion.

We can debate the order, but at the top of the list has to be initial cost vs gasoline-vehicles, lack of charging stations, long trips, etc.

Now let’s compare what I said.

When Do EV Vehicles Make Sense?

-

Currently, nowhere, from a cost standpoint. People buy EVs or hybrids on the questionable belief they are doing something for the environment.

-

For those who very seldom drive at all and for those whom walking, public transportation, or Uber is a viable option, no car of any kind makes economic sense. However, for those who demand the convenience of having a car, the points made below apply.

-

If and when the cost of an EV is no more than the cost of a gas-powered vehicle (factoring in gas, insurance, life of car, maintenance costs) EVs become practical for those who seldom if ever drive more than 150 mile or so before a known lengthy stop that also happens to have a charger. For most, the charging station needs to be home or work.

-

Until batteries charge as fast or nearly as fast fueling a gas-powered vehicle or readily available battery swapping stations exist, EVs will not make sense for a big percentage of drivers.

1-Revisited: “Nowhere, from a cost standpoint,” is very accurate. At a 0.49% rate, the public agrees. Even with California’s incentives the rate only gets to 1.9%. The rest of the country has a laughable 0.25% rate of acceptance.

In 2018 a the plug-in rate for new car sales was a mere 2.1% with most of that in California.

2-Revisited: “For those who seldom drive, buying a car of any kind makes little economic sense.” My statement was accurate.

3-Revisited: If and when the cost of an EV is no more than the cost of a gas-powered vehicle (factoring in gas, insurance, life of car, maintenance costs) EVs become practical for those who seldom if ever drive more than 150 mile or so before a known lengthy stop that also happens to have a charger. For most, the charging station needs to be home or work.

My original statements are accurate. Those who demand the convenience of a car, especially those who make frequent, short trips, EVs are an option. A Tesla for short-haul trips makes no sense.

Readers might point out that driving a Bolt the distance the NYT stated is a mistake, but the point was missed: One should not drive a Bolt long distances unless one is prepared to suffer the consequences experienced by the NYT author.

A 2019 Chevrolet Bolt gets “Up to 238 mile of electric range on a full Charge”. That is certainly pathetic and Tesla owners are right to laugh. I would not buy a Bolt, but some people do. If they do, they should not try to drive long distances.

4-Revisited: “Until batteries charge as fast or nearly as fast fueling a gas-powered vehicle or readily available battery swapping stations exist, EVs will not make sense for a big percentage of drivers.”

That is my exact original statement but I did now emphasize “big percentage”. The statement is entirely accurate.

I could have added that I believe it will happen.

In the body of the article, I stated, “For many, we are a decade away unless and until there are readily available super-fast charging or swapping stations.”

That is certainly accurate, especially because I said “many”, not most. However, “most” may very well be accurate.

Electric Vehicle Sales Forecast

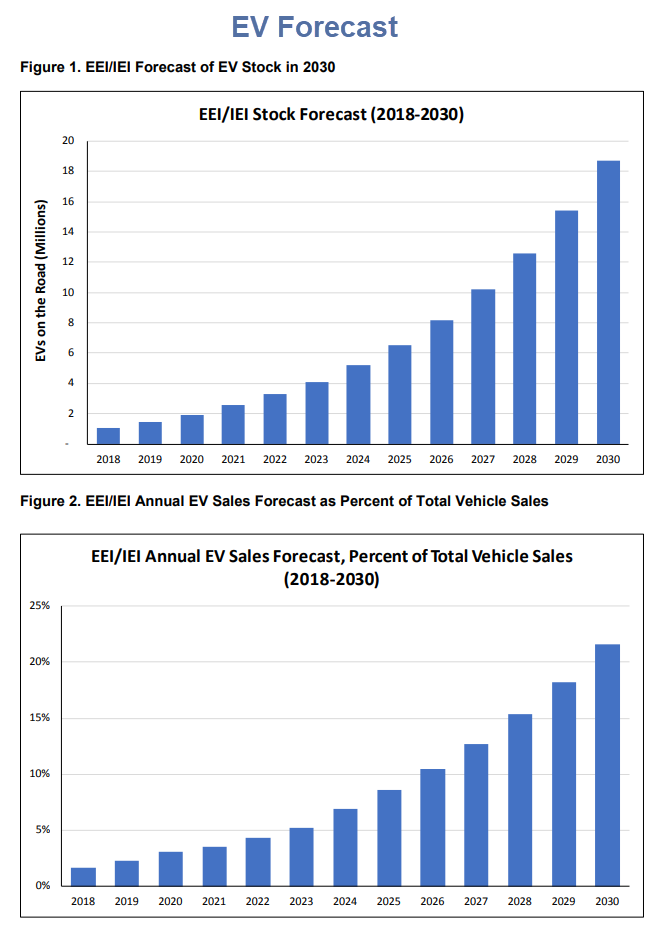

Please consider Electric Vehicle Sales Forecast and the Charging Infrastructure Required Through 2030 by the Edison Foundation Institute for Electronic Innovation.

Key EEI/IEI Points

- The stock of EVs (i.e., the number of EVs on the road) is projected to reach 18.7 million in 2030, up from slightly more than 1 million at the end of 2018. This is about 7 percent of the 259 million vehicles (cars and light trucks) expected to be on U.S. roads in 2030.

- It took 8 years to sell 1 million EVs. We project the next 1 million EVs will be on the road in less than 3 years—by early 2021.

- Annual sales of EVs will exceed 3.5 million vehicles in 2030, reaching more than 20 percent of annual vehicle sales in 2030. Compared to our 2017 forecast, EV sales are estimated to be 1.4 million in 2025 versus 1.2 million.

- About 9.6 million charge ports will be required to support 18.7 million EVs in 2030. This represents a significant investment in EV charging infrastructure.

Mish vs EEI/IEI

The EEI/IEI forecast is that 7% of 259 million cares on US roads in 2030 will be electric.

Let’s assume that forecast is off by a factor of 7. If so, the percentage becomes 49%.

My own forecast is 50%, so I am hardly an EV bear as accused. In fact, I may be a wild-eyed optimist.

Some People Can’t Read

What Happened?

What transpired is a huge number of Tesla and EV owners are defending their purchases. Many of these owners are self-proclaimed, environmentally-superior human beings out to save the world from the evils of cheaper but polluting cars.

These environmental thumpers ignore the coal-burning to produce electricity (about a 30% share), the mining of Lithium, infrastructure costs, and cost of electricity if and when we do get to 50% EV ownership.

Spiraling Environment Cost of Lithium

Wired comments on the Spiraling Environment Cost of Lithium Addiction

Demand for lithium is increasing exponentially, and it doubled in price between 2016 and 2018. According to consultancy Cairn Energy Research Advisors, the lithium ion industry is expected to grow from 100 gigawatt hours (GWh) of annual production in 2017, to almost 800 GWhs in 2027.

“One of the biggest environmental problems caused by our endless hunger for the latest and smartest devices is a growing mineral crisis, particularly those needed to make our batteries,” says Christina Valimaki an analyst at Elsevier.

In South America, the biggest problem is water.

There’s also the potential – as occurred in Tibet – for toxic chemicals to leak from the evaporation pools into the water supply. These include chemicals, including hydrochloric acid, which are used in the processing of lithium into a form that can be sold, as well as those waste products that are filtered out of the brine at each stage. In Australia and North America, lithium is mined from rock using more traditional methods, but still requires the use of chemicals in order to extract it in a useful form. Research in Nevada found impacts on fish as far as 150 miles downstream from a lithium processing operation.

In Argentina’s Salar de Hombre Muerto, locals claim that lithium operations have contaminated streams used by humans and livestock, and for crop irrigation. In Chile, there have been clashes between mining companies and local communities, who say that lithium mining is leaving the landscape marred by mountains of discarded salt and canals filled with contaminated water with an unnatural blue hue.

“Like any mining process, it is invasive, it scars the landscape, it destroys the water table and it pollutes the earth and the local wells,” said Guillermo Gonzalez, a lithium battery expert from the University of Chile, in a 2009 interview. “This isn’t a green solution – it’s not a solution at all.”

So much for the zero pollution idea.

About Tesla

To top it off, the Tesla owners make better-than-thou claims despite spontaneously-exploding batteries, laughable crash-prone automated navigation systems, poor paint jobs, bumpers that fall off, and a myriad of other reported problems that no one sees on any other car in existence.

Public Acceptance

Claims of hatchet jobs are by people who cannot read, don’t understand the points made, and ignore car purchase costs. The group also includes those who mistakenly believe the EVs don’t pollute and Teslas don’t explode.

Public acceptance is where the rubber meets the road. In the US, it’s 2% of new car sales, mostly in California.

If You Build It They Will Come

A friend who lives in DC just pinged me with this comment: “Even here in the East Coast, where it’s non-stop city from DC to NYC, it’s hard to ‘fill up’ an electric car. Until the electric infrastructure is built out, no chance.”

Bingo.

I have a far greater likelihood of this happening than EEI/IEI because I expect a faster rollout. Regardless, two things need to happen.

-

Truly convenient charging that the public accepts.

-

Up front ownership costs in the ballpark of gas-powered cars, also that the public accepts.

States need to build the infrastructure. Imagine 30% EV share on the existing infrastructure. Hour-long waits except at home might just be the norm.

Factor in the fact that condos and apartments buildings likely don’t have charging stations.

“Duh, charge at home“. Yeah, right.

Gonna hang that power cord out the window of a 13-story apartment building?

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2ZGKwUQ Tyler Durden