With Draghi finally admitting that the ECB will never hike even once under his mandate which ends on Oct. 31, and instead indicating two weeks ago at Sintra that the ECB will launch further easing measures in the near term unless the outlook improves – which won’t, judging by the latest woeful European PMIs – the question has turned to just what dovish options the ECB has, and/or may reveal as soon as this month.

Commenting on this eventuality, over the weekend Goldman’s Sven Jari Stehn writes that “given sluggish growth, persistent geopolitical risks and subdued inflation expectations, we expect the Governing Council to provide an easing package, most likely at the September meeting” and proceeds to discuss the ECB’s easing options and their possible effectiveness.

The analysis starts with the most mundane of options: another rate cut.

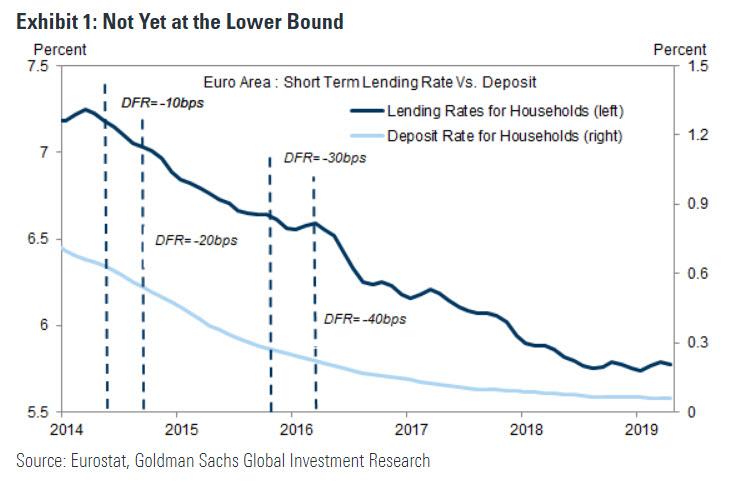

Here, as Goldman explains, the effectiveness of further cuts to the deposit rate will depend on two main issues in the current context. The first is whether further cuts into negative territory would be passed into bank lending rates given weak bank profitability. Since the deposit rate was lowered below zero in mid-2014, bank deposit rates have been “sticky” and responded little to further rate cuts (Exhibit 1). Bank lending rates have still fallen, but less than in normal times. As a result, bank net interest margins have declined which, in turn, has further reduced incentives to lower lending rates.

A key point made by the Goldman strategist is that the pass-through from further deposit rate cuts into bank lending rates remains positive but will diminish further from here. Moreover, there is evidence that further rate cuts might start pushing up bank lending rates as the deposit facility rate approaches -1%, a point which has been dubbed the “reversal rate.” In other words the ECB can cut another roughly 50-60bps before its easing loses effectiveness. As a result, Goldman’s analysis suggests that the ECB can cut rates somewhat further from here, even though the resulting boost to retail interest rates would likely be smaller than usual.

Meanwhile, ECB officials have discussed measures to mitigate the effects of negative interest rates on bank profitability – which even some European central bankers now admits is being hindered due to NIRP – which might help to cushion the weakening of the bank transmission channel. The leading option is a tiered reserve system, where banks can avoid paying a negative interest rate on a portion of their excess reserves at the ECB.

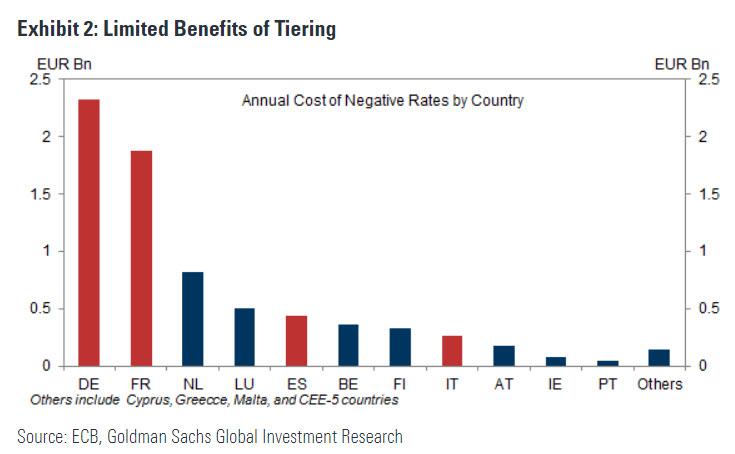

As discussed previously, the benefits of a tiered system are likely to be limited and asymmetrically distributed across the Euro area, as Goldman shows in the next chart.

This is because the costs of negative rates are concentrated in core economies—mainly France and Germany—where the majority of excess reserves are held. Banks are currently paying a total of around € 8bn per year on their excess reserves at the ECB. A tiering system that shields 50% of excess reserves from negative rates would, for example, provide annual relief of €4bn for the Euro area banking system (or around 3% of profit before tax in 2017). The relief from tiering would rise proportionally with further rate cuts and a renewed expansion of the ECB’s balance sheet, which would increase excess liquidity. But even then the benefits of tiering would be limited and skewed heavily towards banks in France and Germany.

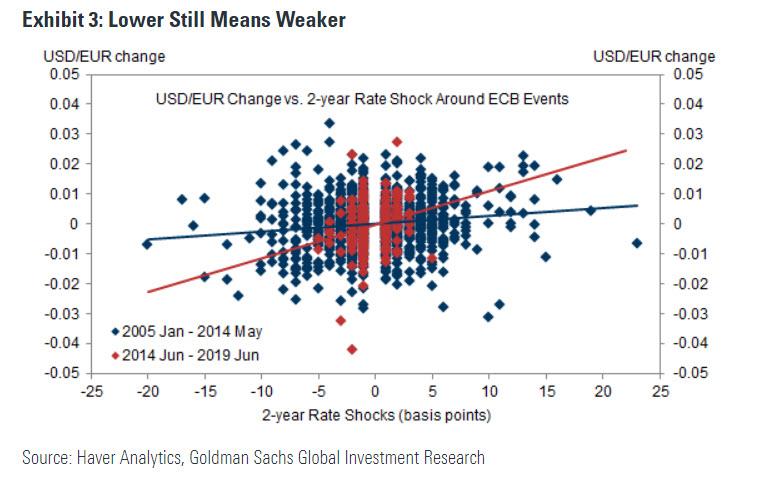

The second key transmission channel of lower policy rates is the exchange rate, according to Goldman, which notes that the Euro has appreciated notably since the both Draghi’s (oops) and Powell’s dovish message in June as Goldman now expects the FOMC to cut the funds rate by 25bp in each of July and September. According to bank estimates, the sensitivity of the Euro to ECB policy surprises has risen quite notably since the deposit rate entered negative territory .

This underscores the ECB’s incentive to try to limit Euro appreciation in response to Fed cuts, especially if the FOMC cuts by 50bp in July.

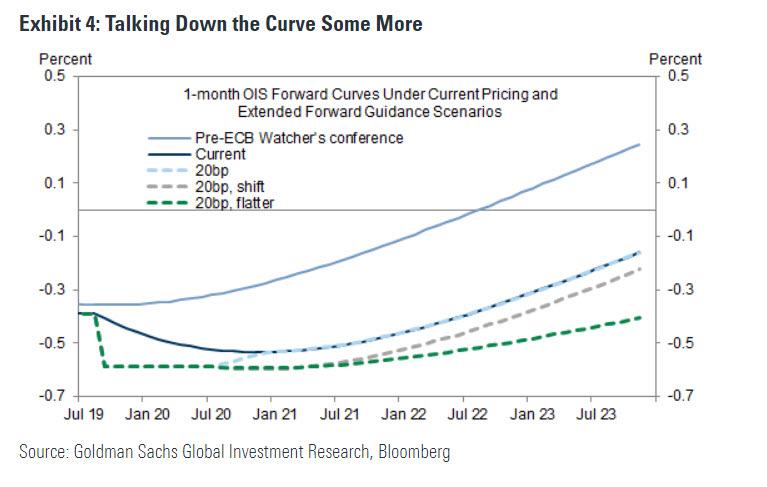

Another option for master of jawboning is for Mario “Whatever it Takes” Draghi, to further strengthen the bank’s forward guidance. As a result, Goldman thinks it is likely that ECB officials will reintroduce the easing bias at the July meeting, indicating that policy rates could go lower from here. Beyond this, the Governing Council could provide a further extension of its date-based guidance, either by pushing out the “mid-2020” calendar date or by tying lift-off to the end of QE.

Here, an alternative, and more aggressive, approach would be to adopt a quantitative criterion to guide expectations for lift-off. For example, the Governing Council could indicate that rates will be on hold until year-over-year core HICP inflation has reached a certain threshold (such as 1.75%). Connecting lift-off to inflation pressures—rather than the calendar—would be appealing and our simulations show that the benefits could be significant. Three stylised paths for how the Governing Council could steer expectations of the policy rate path to provide additional accommodation are shown below. The first shows a 20bp rate cut without additional guidance about the path. The second and third paths show scenarios where the ECB succeeds to push out and flatten the EONIA curve by strengthening the state-based forward guidance.

What about a return to QE?

As a reminder, the ECB ended its QE program, which it had been tapering in 2018, at the start of 2019. In retrospect, this may have been a big mistake.

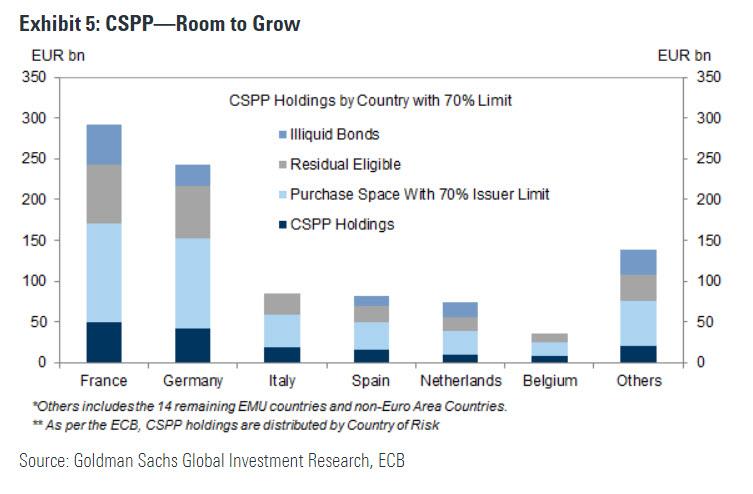

As Goldman notes, a return to QE at full throttle is complicated by the ECB’s self-imposed limits on purchases of public sector securities. But there is still hope, as significant room to expand corporate sector purchases remains, even under current limits. Goldman’s credit strategists see scope for additional purchases to the tune of around €400bn, which are heavily skewed towards French and German issuers.

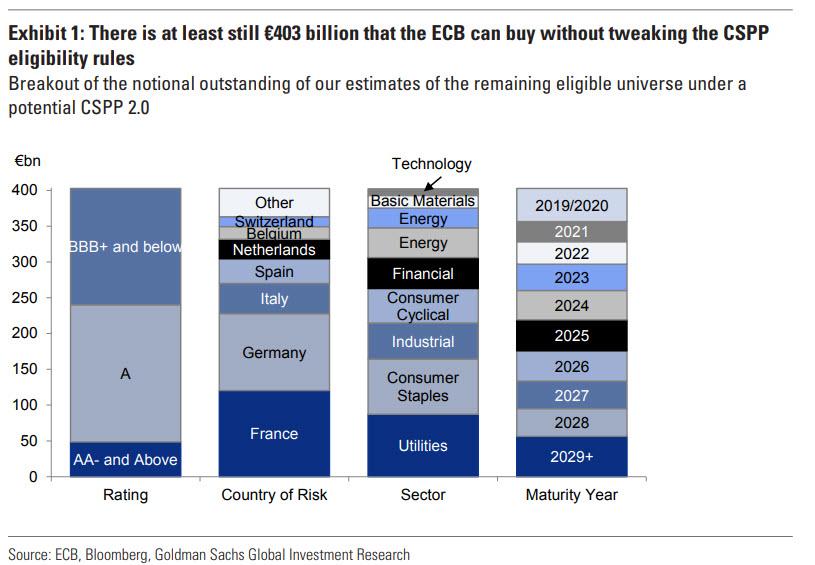

Some details on how Goldman got to this number: the bank assumes the ECB will keep the same eligibility criteria relative to CSPP 1.0, including restricting the purchases to non-bank issuers and maintaining the limit per ISIN to 70%. Second, Goldman assumes the current bond constituents of the CSPP portfolio capture the universe that the ECB can effectively target. On this estimates, the combined par value outstanding of the ISINs currently owned by the ECB is €814 billion, which is smaller than the size of the €952 billion worth of bonds that the ECB can theoretically target (again assuming the CSPP 1.0 criteria continue to apply). The extra €138 billion that the “theoretical” universe of eligible bonds comprises likely includes illiquid bonds with high ownership concentration that are hard to acquire in the secondary market. Applying the 70% limit to the €814 billion of eligible bonds outstanding and subtracting the current par value of the ECB portfolio which is estimated to be at €168bn, Goldman’s analysts get a lower bound estimate of the universe of eligible bonds of €403 billion. Exhibit 1 provides the ratings, country, sector, and maturity breakdowns of the universe of eligible bonds.

While the theoretical purchase space is around €100bn larger, the ECB has not been able to tap these bonds during the first corporate QE programme. Which is why sourcing all eligible bonds therefore looks like a stretch.

In addition, the monthly purchase pace of corporate QE is likely to be limited in practice by liquidity conditions. A pace of EUR 3-5bn seems feasible, with purchases targeting primary issuance rather than outstanding bonds.[7] We therefore think that corporate purchases of up to EUR 5bn are likely to be part of any return to QE.

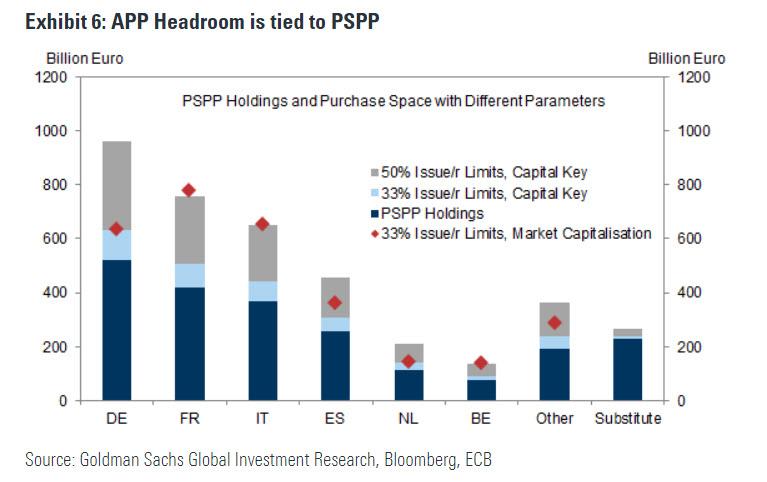

As such, with a limited flow of corporate purchases, sovereign purchases will be necessary to achieve a meaningful monthly purchase volume. Under the current self-imposed limits (especially the 33% issue/issuer limits and country allocation according to capital key) Goldman calculates that the ECB could buy up to €400bn sovereign and agency bonds with limited need for substitute purchases.

Should the ECB relax the issue and issuer limits to 50% would almost quadruple the purchase space to around EUR 1,500bn (light blue and grey bars). Maintaining the 33% issue and issuer limits, while switching to a country allocation following market capitalization, instead, would lift the available purchase space in countries with large sovereign debt markets, such as France and Italy (red diamonds). But it would not relax the limits in Germany beyond the available purchase space under current parameters.

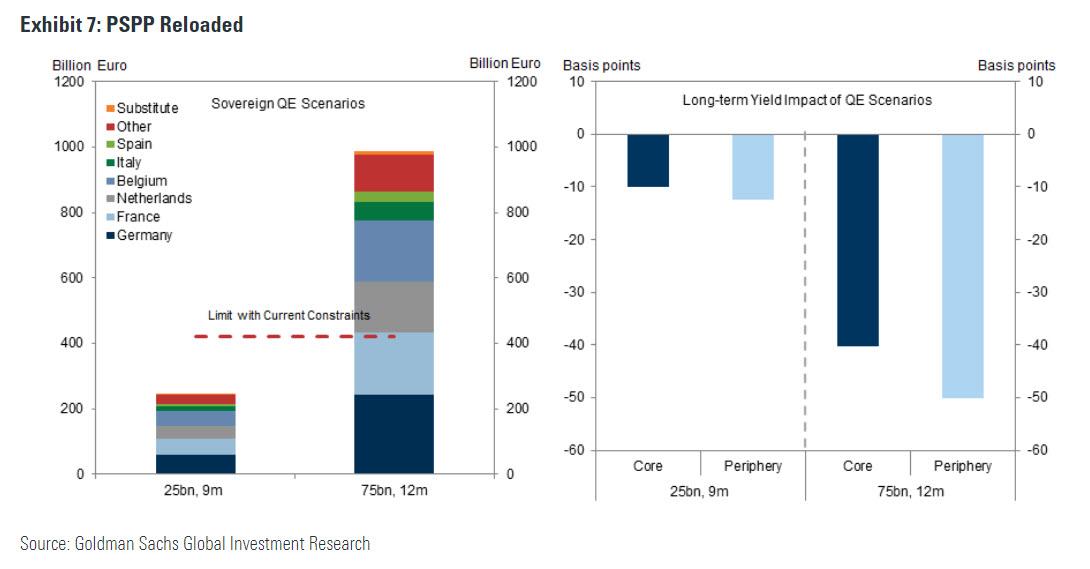

Here Goldman warns that while in theory the ECB has significant runway, in practice, the central bank will not be able to expand the purchase space up to these theoretical limits under any parameter constellation due of liquidity concerns and scarce supply in certain bond market segments. On balance, Goldman’s estimates point to limited headroom under the current programme parameters to extend sovereign QE as suggested by President Draghi in his Sintra speech. For instance, an extension by nine months at a pace of EUR 25bn looks feasible (Exhibit 7, left panel).

However, beyond that Stehn sees significant political, legal and reputational hurdles to a relaxation of the issue and issuer limits, as well as the capital key allocation principle. Should the ECB nonetheless lift the current constraints, a relaxation of the issue and issuer limits looks more likely than a move away from the capital key. With this change a longer extension of the programme—say for twelve months—at a substantially higher monthly purchase pace—such as €75bn—would become feasible, translating in roughly $1 trillion in asset purchases by the ECB in one year.

On the other hand, implementing a small extension of sovereign QE would have a limited impact on long-term Euro area yields through the extraction of duration risk based on Goldman’s prior estimates (Exhibit 7, right panel). At the same time, such an announcement could be interpreted as a powerful signal that more QE is in the pipeline and hence have an outsized yield effect relative to its limited volume. Finally, any modification of the technical parameters could be complemented by a maturity “twist” towards longer-dated securities. This would increase the duration absorption of ECB purchases and elicit larger yield effects.

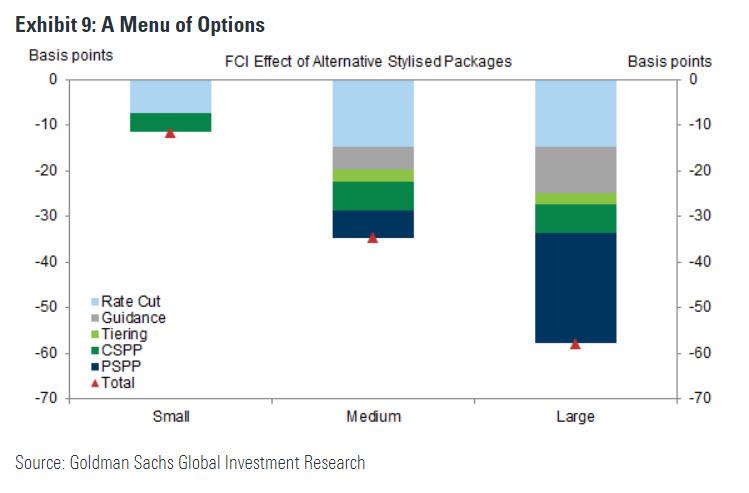

Putting these proposals together, Goldman considers three hypothetical bundles.

- First, a “small” program which includes a 10bp deposit rate cut and corporate purchases (scaled to EUR 5bn per month for six months).

- Second, Goldman constructs a “medium” package which includes a 20bp rate cut with tiering, somewhat stronger forward guidance, corporate purchases (EUR 5bn per month for nine months) and limited sovereign purchases (EUR 25bn per month for nine months).

- Third, the bank considers a “large” package that contains more aggressive sovereign purchases (scaled to EUR 75bn per month for twelve months) via an increase in the issuer limit, in addition to the other elements in the medium package.

In terms of practical consequences, Goldman finds that the small package would provide a limited boost to financial conditions of around 10bp. The medium package could have notably larger effects, easing our FCIs by 30-40bp, mainly via the rate cut and the enhanced forward guidance. The large package would, obviously, bring the FCI to around 60bp, as sovereign QE provides a significantly bigger effect. In terms of the real-world, the bank’s estimates suggest that the medium package might boost area-wide growth by 0.3-0.4pp over the subsequent year., and modestly more for a full-blown QE package.

While those are the theoretical constructs the ECB is facing, looking at next steps, Goldman expects the Governing Council to adopt the “or lower” easing bias for policy rates in July and indicate that the ECB will analyze QE options for September. At that point look for an easing package that closely resembles the “medium” package discussed above, including a 20bp rate cut with tiering, enhanced forward guidance and a return to QE.

Furthermore, Goldman expects the asset purchases to include corporate bonds and sovereign debt within the existing PSPP headroom, paired with a signal that the Governing Council stands ready to expand the sovereign purchase program with an increase in the issuer limit if economic conditions do not improve.

Finally, while earlier action is possible, the September meeting appears the most likely given new staff projections and the timing of the next FOMC meeting, which is at the end of July 30-31.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2RNg2O4 Tyler Durden