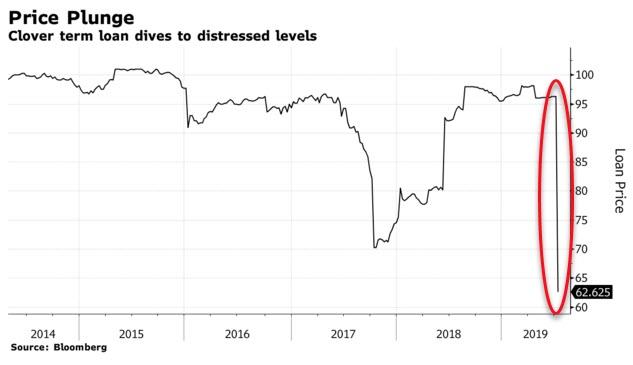

A leveraged loan taken out by a company called Clover Technologies about five years ago lost about a third of its value without warning over the past week, according to Bloomberg. The “alarming” and “abrupt” collapse of the recycling company’s debt surprised even sophisticated investors that deal in leveraged loans.

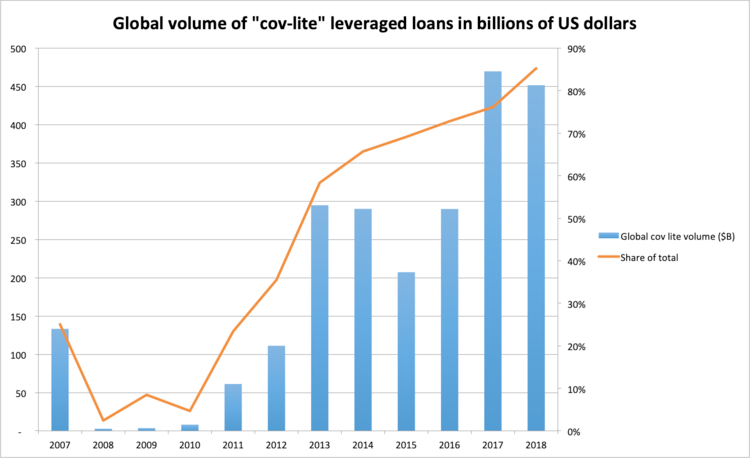

And even though the loan isn’t large by Wall Street standards – $693 million – it serves as a much needed and stark reminder of the capital that has flocked to leveraged loans in search of yield. The leveraged loan market today is $1.3 trillion and low rates have caused an explosion in borrowing and lax standards in underwriting. The market can also be thin, and this means that collapses like Clover’s can happen quickly and without warning.

Soren Reynertson of investment bank GLC Advisers & Co said:

“When buyers head for the exits at the same time, prices can drop fast and furiously given the lack of liquidity.”

Clover had been operating since 1996 when it was an acquired by Golden Gate in 2010 for an undisclosed sum. Golden Gate piled debt onto the underlying company to extract dividends from it using the leveraged loan market as a wallet. The company took out loans that funded dividend payments totaling at least $278 million and then the company went back to the loan market in 2014, asking lenders for $100 million extra to make an acquisition.

The loans were bought mostly by mutual funds and collateralized loan obligations, which bundle this type of debt into higher rated securities. And there’s been little trouble finding buyers for CLOs in recent years, with high grade bond yields hovering near zero.

Clover’s loan deal was known as “covenant light” and contained no covenants that required the company to alert investors to signs of trouble after undergoing a financial test every quarter. This means that investors had little leverage over the company.

Jessica Reiss, head of leveraged loan research at Covenant Review, called the influx of covenant light loans “death by 1000 paper cuts.”

Clover’s substantial debt left little room for error and it wasn’t long until the company began struggling. In 2014, S&P lowered the company’s outlook to negative and Moody’s and S&P both downgraded it four years later. Regardless, the loan held most of its value in the secondary market until July 9.

That’s when Clover disclosed that it lost two key customers and had hired advisers to evaluate strategic options.

The loan quickly plummeted from $.97 to about $.65 and, two days later, Moody’s downgraded the company again to Caa3, citing its “aggressive financial policies, evidenced by its private equity ownership and history of shareholder distributions and large debt-funded acquisitions.’’

The downgrade didn’t help things – rather, it created a ton of offers from people that were likely forced to dump the loans due to the distressed rating. Moody’s is now predicting that Clover will likely default on its debt obligations going forward.

The ratings agency cites concerns over long-term viability of the business and “unexpected” operational developments. Its debt is just over 6 times its earnings, a level that typically raises lender concerns about the company’s ability to meet its financial obligations. Another warning sign came in May when the company pulled a seemingly attractive refinancing plan that offered a high yield of nearly 9% with a short, three-year maturity.

Other companies, like American Tire Distributors and Diebold Nixdorf Inc., experienced similar bond blowups in the credit market over the past few years.

Reynertson concluded: “Highly levered companies are even more sensitive to reductions in revenue. Cash flows can evaporate overnight.”

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2O59zA2 Tyler Durden