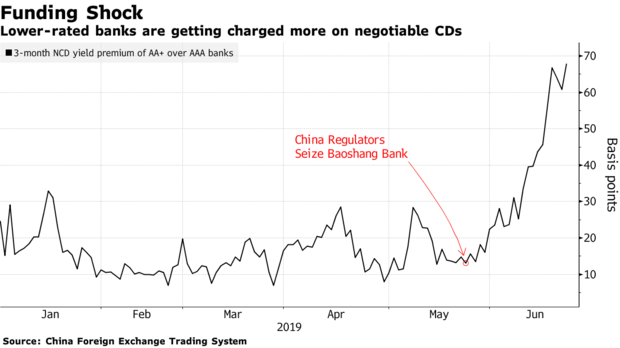

Ever since the unexpected failure of China’s Baoshang Bank in late May, which caused a freeze in the interbank market among smaller, less credible (and government bankstopped) banks, and which sent rates on Negotiable Certificates of Deposit (NCDs), various bank bonds and assorted report rates sharply higher…

… investors have fretted that China appears on the verge of a “Lehman moment”, where wholesale interbank liquidity and overnight funding markets suddenly lock up. The reason for this, as we explained last month, is that China’s short-term lending market for banks and other financial institutions has for years operated under the assumption that Beijing wouldn’t allow big losses in the event of defaults or insolvencies (hence the reason why Baoshang’s failure was a shock). That confidence has been shaken by regulators’ unusual public takeover of the troubled Chinese bank near Mongolia last month, and the even more stunning public admission by the central bank that “not all of Baoshang Bank’s liabilities would necessarily be guaranteed.”

“Bank failure always causes greater concern given systemic fears,” said Owen Gallimore, head of credit strategy at Australia & New Zealand Banking Group, suggesting greater pressure on the private sector ahead.

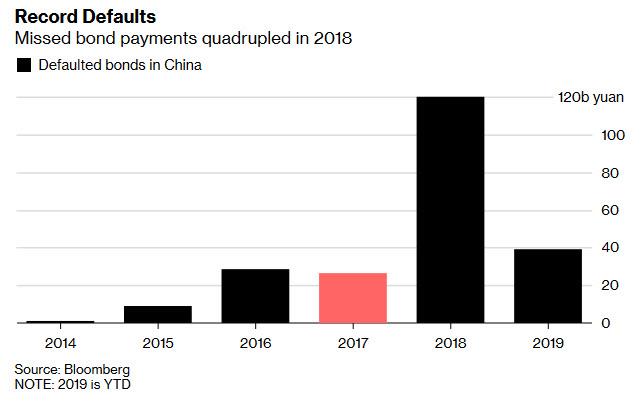

Naturally, with China growing at the slowest pace in recent history, beset by shadow bank deleveraging, trade war, a shaky transition to a consumer economy and China’s first ever current account deficit, these stresses come at a very bad time for the normal functioning of the local economy.

Furthermore, nonbank borrowing through bond repos and interbank loans skyrocketed since China’s central bank began easing monetary policy in early 2018, hitting a net 74 trillion yuan ($10.7 trillion) in the first quarter of 2019, according to Enodo Economics, and up nearly 50% from a year earlier. As the WSJ redundantly warns, “funding troubles for brokerages and other asset managers therefore pose big problems for both financial stability and the real economy.”

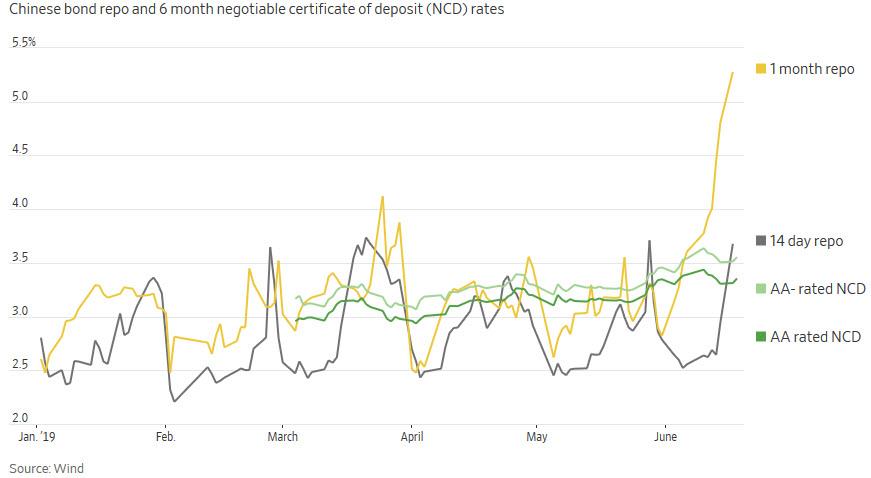

Meanwhile, as we warned as far back as March 2017, problems would eventually migrate from the smallish market for negotiable certificates of deposit, used mostly by small banks, into the vastly greater bond repo market. Here, while key one-day and seven-day weighted average borrowing rates had remained low thanks to huge central bank cash injections – such as the 250BN yuan we described back in May – longer tenors such as the 1 month repo have marched sharply higher.

As an aside, for those asking why NCD’s matter, the answer is because as we first explained two years ago, numerous smaller banks had become acutely reliant on such shadow banking funding mechanisms as Certificates of Deposit, which had become the primary source of short-term funding for many of China’s banks mid-size and smaller banks.

As Deutsche Bank further explained, the banks most exposed to a shut down in this “shadow funding” pathway are medium-sized and small banks – such as Baoshang – for whom wholesale funding made up 31% and 23%, a number that has risen substantially in the interim period.

Some more background: in China, the funding flow goes like this (per Bloomberg): big national banks lend to smaller regional lenders, which then provide financing to non-bank peers such as brokerages and funds. They in turn use the money to invest in corporate bonds.

“Smaller banks play a key role in this chain,” said Ming Ming, chief fixed-income analyst of Citic Securities Co. Right now investors are quite “risk averse and everyone wants to mitigate counterparty risks. If things get worse, China’s financial market liquidity could collapse,” he added.

In this context, troubles with NCD funding are troublesome, because as Bloomberg reported recently, in the aftermath of the Baoshang seizure, some Chinese banks and securities firms “tightened requirements for negotiable certificates of deposits that are used as collateral for funding.” In some cases, private NCDs were shunned altogether, and some financial institutions now only accept NCDs sold by state-owned and joint stock banks as collateral while some have refused to lend money to investors pledging NCDs issued by lenders rated AA+ and below for now.

Worse, as Bloomberg followed up last month, the interbank market had started to also freeze up as a result of counterparty suspicions: one month after Baoshang, Chinese bond traders in China are “rethinking counterparty risks as shock waves from a government takeover of a bank ripple through the country’s financial markets.”

As a result, and in an ominous echo of what happened before, and certainly after the Lehman failure, it suddenly got far harder for corporate bonds to be accepted as collateral for repo financing as lenders increasingly demand top quality bonds such as Chinese sovereign bills and policy bank notes as pledges, with Bloomberg noting that “traders are having second thoughts on taking even AAA rated short-term bank debt as security in the wake of last month’s seizure of Baoshang Bank”

As a result, funding among China’s financial institutions has become clogged, in some cases to the point of paralysis, which has already caused borrowing costs to spike for brokerages and smaller banks. All this could mean even higher default rates one year after China reported the highest amount of bonds defaults in modern history.

Meanwhile, in the aftermath of the Baoshang failure, one of the most opaque areas of China’s credit markets – the practice of companies buying their own bonds – has been getting far tougher, and is further contributing to financing difficulties that are already bedeviling the nation’s policy makers.

As Bloomberg discussed last month, at issue is a sharp increase in scrutiny by financial institutions of the collateral that their counterparties offer up in the repurchase market, a crucial channel for short-term funding. If the debt sold by issuers that indirectly purchased a portion of their own bonds – which could account for as much as 8% of China’s corporate bonds, according to Citic Securities – is shunned, that would squeeze liquidity for a swathe of the nation’s businesses, a funding freeze that spreads beyond China’s banking sector and affects even the highest quality corporations.

That’s precisely what appeared to be happening over the past two months when despite regulators’ best efforts to a potentially catastrophic seizing up in the repo market and short-term collateralized lending between banks, some institutions moved to avoid riskier securities. The moves, as Bloomberg notes, “showcased the fragility of confidence toward borrowers that lack state backing in a financial system still dominated by state-sector banks.”

Conditions became especially challenging for firms that obtained funding via unorthodox methods: one such practice is known as “structured issuance”, where a company transfers cash to an asset manager to buy a slice of the bonds the company is itself selling. The manoeuvre helps give the appearance of greater demand for its securities and stronger ability to obtain funding. What could make the practice untenable is if asset managers can no longer use those securities held in custody as collateral for repos.

“Since some repo transactions have defaulted recently, it is unclear whether companies can continue to borrow money from the structured issuance method, said Meng Xiangjuan, chief fixed-income analyst at SWS Research Co. in Shanghai. “If it stops, some issuers will certainly face difficulties operating their business normally, and their debt-repayment pressure will rise,” she said.

It gets worse.

As Bloomberg reported recently, while the practice of self-financing a portion of bond issuance is well known among credit analysts and ratings companies, “observers have been loath to name the firms involved, making this a particularly murky part of China’s debt market.” Citic Securities, for its part, hazarded a total of about 1.5 trillion yuan ($218 billion) worth of securities outstanding that were sold in part via structured issuance.

And so, in addition to the somewhat specialized NCD market, the one place where China’s creeping funding freeze has become apparent is in the repo market, which is collateralized by bonds and other securities which the market no longer accepts at fave value.

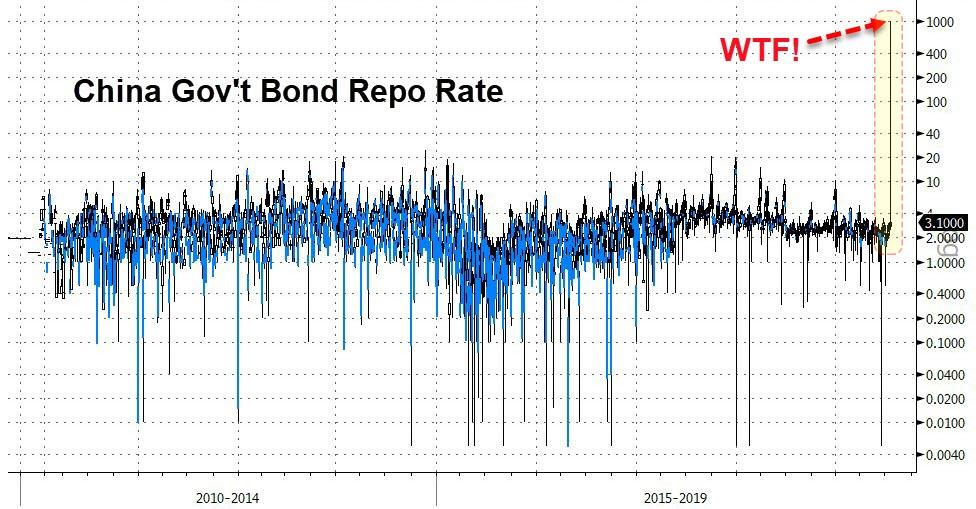

This creeping “Ice Nining” of China’s banking system, and its closest encounter with the proverbial “Lehman moment” yet, came overnight when, inexplicably, the four-day repo rate on China’s government bonds (i.e., the cost for investors to pledge their Chinese government bond holdings for short-term funding) on the Shanghai exchange briefly spiked to 1,000% in afternoon trading!

It is unclear what may have snapped, because as of 3:30pm local time, the repo rate had fallen back to 3.1%, which begs the question: did some bank just have a sudden liquidity run/freeze and was willing to pay anything for immediate access to funding? An exchange official had no idea what had caused the massive spike, and an official told Bloomberg that the Shanghai exchange needs to check details of the trade before it can comment.

To be sure, it may well have been a fat finger: back on July 8, the PBOC said it had suspended some traders at Ping An Bank and China Merchants Bank for a year for involvement in “abnormal” trades, when the two lenders were involved in overnight bond repo trades in the interbank market that put the price at 0.09% on July 2, the PBOC said.

However, that was a fat finger that sent repo lower, and there have been numerous such instances in the past. What is odd, and what makes the overnight move unique, is that this was the first time ever that the government repo rate shot up.

So was this a hint that China’s (long overdue) Lehman moment is finally upon us?

While we wait for the Shanghai exchange to give the “official” version of events, there is some good news: one reason for optimism is that the Fed is now certain to cut rates at the end of the month. Recall that the last time China’s money markets locked up over counterparty risks, was in the aftermath of brokerage Sealand Securities’ initial refusal to pay out on a repo-like agreement in late 2016, when the Fed was in tightening mode. As the WSJ’s Nathaniel Taplin writes, “a dovish Fed gives China’s central bank more room to cushion any further money-market ructions with ample liquidity without worrying too much about destabilizing capital outflows.”

It would be ironic if China’s “white knight” savior from repocalpyse is none other than the Fed.

Alas, here too there is more back news: unlike now, in late 2016 China’s economy was improving and so was corporate creditworthiness. That is no longer the case, and as such, investors should keep a very close eye on China’s money markets in the days ahead to make sure that the spike to 1,000% was a one-off event. One or more such unprecedented lock ups in the interbank market, and a repo market freeze that until now was relegated to a handful of banks and brokerages will promptly “contaminate a fragile financial ecosystem”, one which as the Baoshang shock of May 24 shows, is no longer unreservedly backstopped by Beijing.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/32F6wSs Tyler Durden