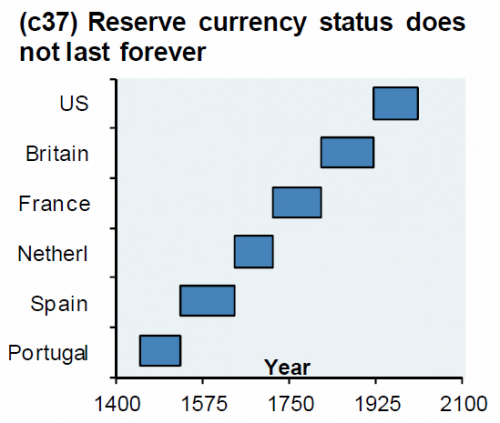

Almost eight year ago, we first presented a chart first created by JPMorgan’s Michael Cembalest, which showed very simply and vividly that reserve currencies don’t last forever, and that in the not too distant future, the US Dollar would also lose its status as the world’s most important currency, since it is never different this time.

As Cembalest put it back in January 2012, “I am reminded of the following remark from late MIT economist Rudiger Dornbusch: ‘Crisis takes a much longer time coming than you think, and then it happens much faster than you would have thought.'”

Perhaps it is not a coincidence then that in light of the growing number of mentions of MMT and various other terminal, destructive monetary policies that have been proposed to kick on the current financial system the can just a little bit longer, that the topic of longevity of reserve currency status is once again becoming all the rage, and none other than JPMorgan’s Private Bank ask in this month’s investment strategy note whether “the dollar’s “exorbitant privilege” is coming to an end?”

So why is JPM, after first creating the iconic chart above which has since spread virally across all financial corners of the internet, not only worried that the dollar’s reserve status may be coming to an end, but in fact goes so far as to state that “we believe the dollar could lose its status as the world’s dominant currency (which could see it depreciate over the medium term) due to structural reasons as well as cyclical impediments.”

Read on to learn why even the largest US bank has started to lose faith in the world’s most powerful currency.

Is the dollar’s “exorbitant privilege” coming to an end?

In Brief

The U.S. dollar (USD) has been the world’s dominant reserve currency for almost a century. As such, many investors today, even outside the United States, have built and become comfortable with sizable USD overweights in their portfolios. However, we believe the dollar could lose its status as the world’s dominant currency (which could see it depreciate over the medium term) due to structural reasons as well as cyclical impediments.

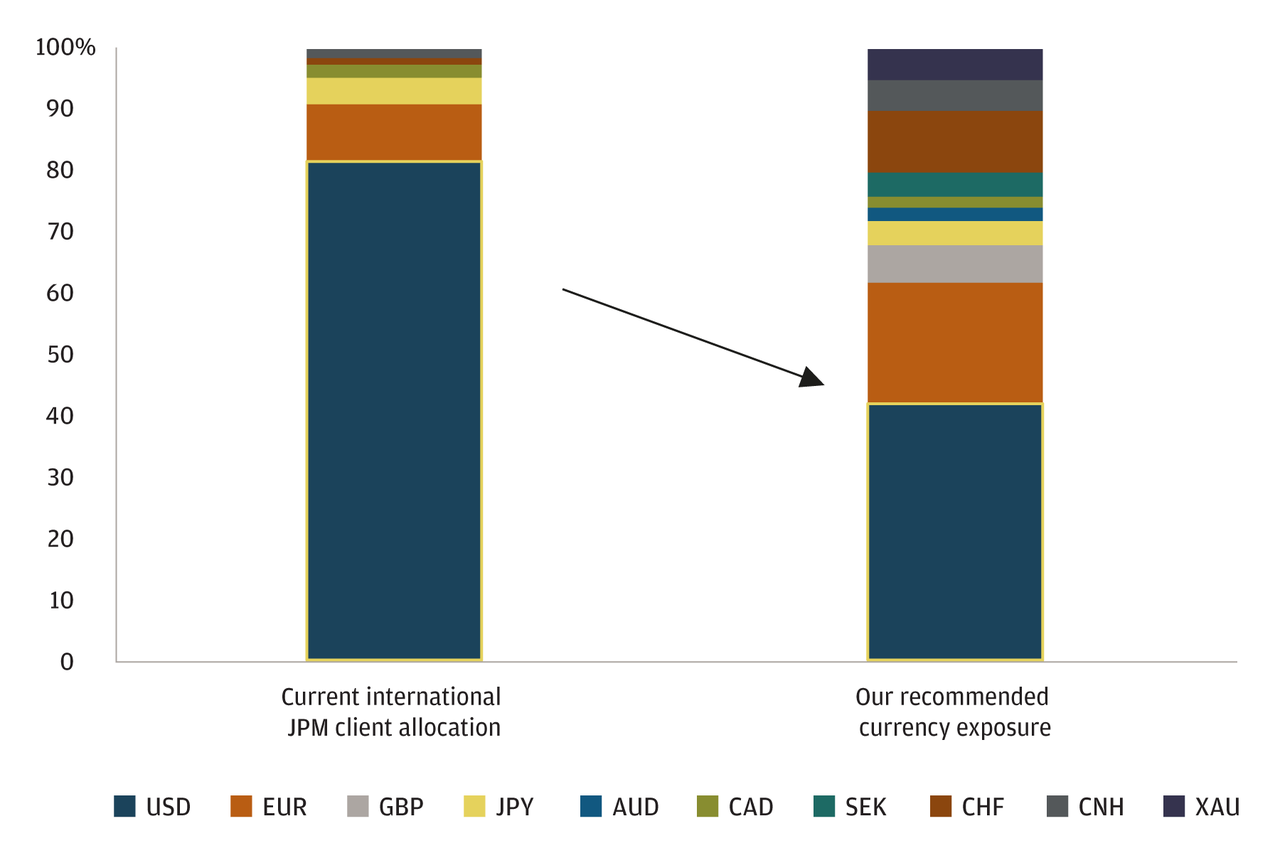

As such, diversifying dollar exposure by placing a higher weighting on other currencies in developed markets and in Asia, as well as precious metals makes sense today. This diversification can be achieved with a strategy that maintains the underlying assets in an investment portfolio, but changes the mix of currencies within that portfolio. This is a completely bespoke approach that can be customized to meet the unique needs of individual clients.

The rise of the U.S. dollar

It is commonly perceived that the U.S. dollar overtook the Great British Pound (GBP) as the world’s international reserve currency with the signing of the Bretton Woods Agreements after World War II. The reality is that sterling’s value was eroded for many decades prior to Bretton Woods. The dollar’s rise to international prominence was fueled by the establishment of the Federal Reserve System a little over a century ago and U.S. economic emergence after World War I. The Federal Reserve System aided in the establishment of more mature capital markets and a nationally coordinated monetary policy, two important pillars of reserve-currency countries. Being the world’s unit of account has given the United States what former French Finance Minister Valery d’Estaing called an “exorbitant privilege” by being able to purchase imports and issue debt in its own currency and run persistent deficits seemingly without consequence.

The shifting center

There is nothing to suggest that the dollar dominance should remain in perpetuity. In fact, the dominant international currency has changed many times throughout history going back thousands of years as the world’s economic center has shifted.

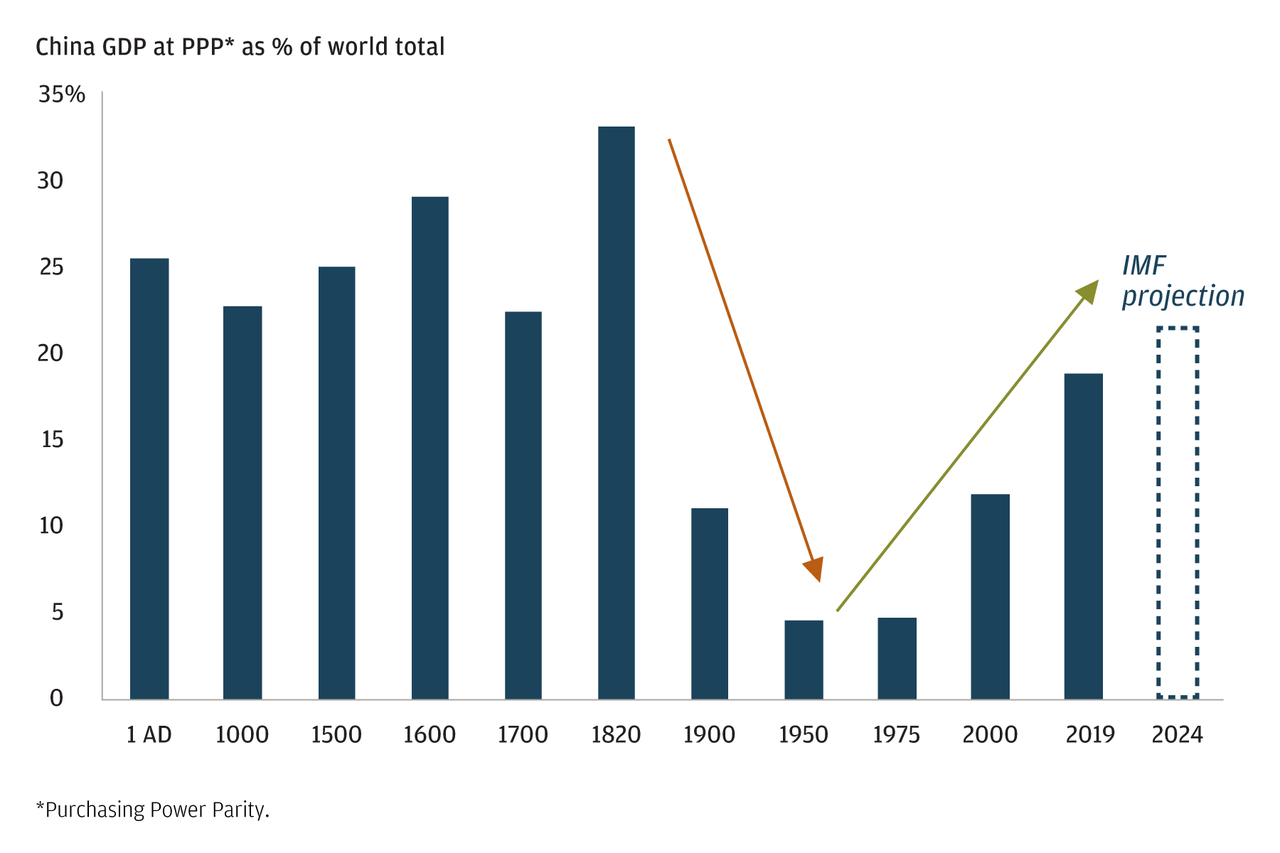

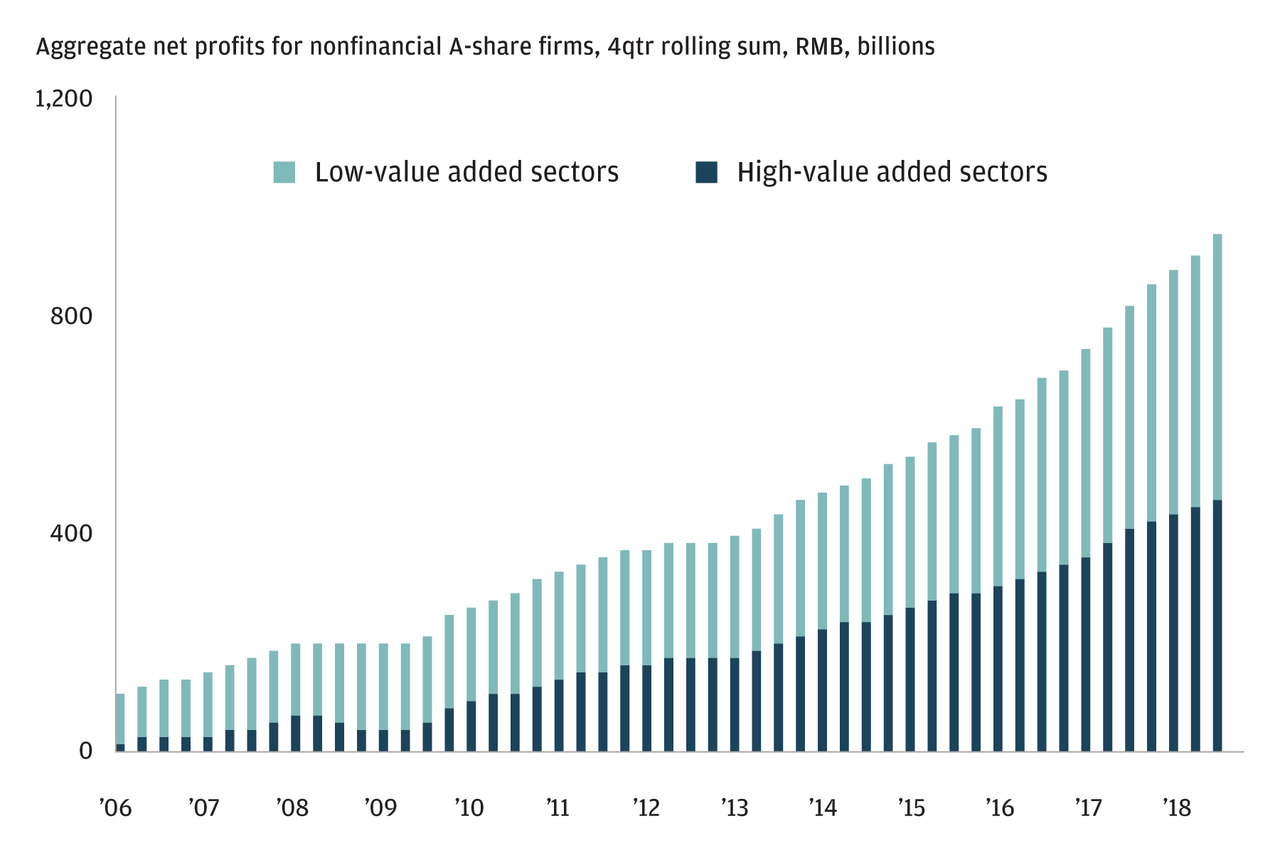

After the end of World War II, the U.S. accounted for biggest share of world GDP at more than 25%. This number is brought to more than 40% when we include Western European powers. Since then, the main driver of economic growth has shifted eastwards towards Asia at the expense of the U.S. and the West. China is at the epicenter of this recent economic shift driven by the country’s strong growth and commitment to domestic reforms. Over the last 70 years, China has quadrupled its share of global GDP to around 20%—roughly the same share as the U.S.—and this share is expected to continue to grow in the years ahead. China is no longer just a manufacturer of low cost goods as a growing share of corporate earnings is coming from “high value add” sectors like technology.

China regaining its status as a global superpower

Earnings in China are becoming more balanced

In addition to China, the economies of Southeast Asia, including India, have strong secular tailwinds driven by younger demographics and proliferating technological know-how. Specifically, the Asian economic zone—from the Arabian Peninsula and Turkey in the West to Japan and New Zealand in the East and from Russia in the North and Australia in the South—now represents 50% of global GDP and two-thirds of global economic growth. Of the estimated $30 trillion in middle-class consumption growth between 2015 and 2030, only $1 trillion is expected to come from today’s Western economies. As this region grows, the share of non-USD transactions will inevitably increase which will likely erode the dollar’s “reserveness”, even if the dollar isn’t replaced as the dominant international currency.

In other words, in the coming decades we think the world economy will transition from U.S. and USD dominance toward a system where Asia wields greater power. In currency space, this means the USD will likely lose value compared to a basket of other currencies, including precious commodities like gold.

Dollar’s declining role already under way?

Recent data on currency reserve holdings among global central banks suggests this shift may already be under way. As a share of overall central bank reserves, the USD’s role has been declining ever since the Great Recession (see chart). The most recent central bank reserve flow data also suggests that for the first time since the euro’s introduction in 1999, central banks simultaneously sold dollars and bought euros.

Central banks across the globe are also adding to gold reserves at their strongest pace on record. 2018 saw the strongest demand for gold from central banks since 1971 and a rolling four-quarter sum of gold purchases is the strongest on record. To us, this makes sense: gold is a stable source of value with thousands of years of trust among humans supporting it.

USD share of central bank reserves, %

Trade Wars have long-term consequences

The current U.S. administration has called into question agreements with nearly all of its largest partners—tariffs on China, Mexico and the European Union, renegotiating NAFTA, as well as abandoning the Trans Pacific Partnership. A more adversarial U.S. administration could also encourage countries to reduce their reliance on USD in trade. Currently 85% of all currency transactions involve the USD despite the U.S. accounting for only roughly 25% of global GDP.

Countries around the world are already developing payment mechanisms that would avoid using the dollar. These systems are small and still developing but this is likely to be a structural story that will extend beyond one particular administration. In a recent speech on the international role of the euro, Bank for International Settlements Chief Economist Claudio Borio brought up the benefits of pricing oil in the euro saying, “Trading and settling oil in the euro would move payments from dollars to euros and thereby shift ultimate settlement to the euro’s TARGET2 system. This could limit the reach of U.S. foreign policy insofar as it leverages dollar payments.” The European Central Bank also alluded to this theme in a recent report saying that “growing concerns about the impact of international trade tensions and challenges to multilateralism, including the imposition of unilateral sanctions seem to have lent support to the euro’s global standing.”

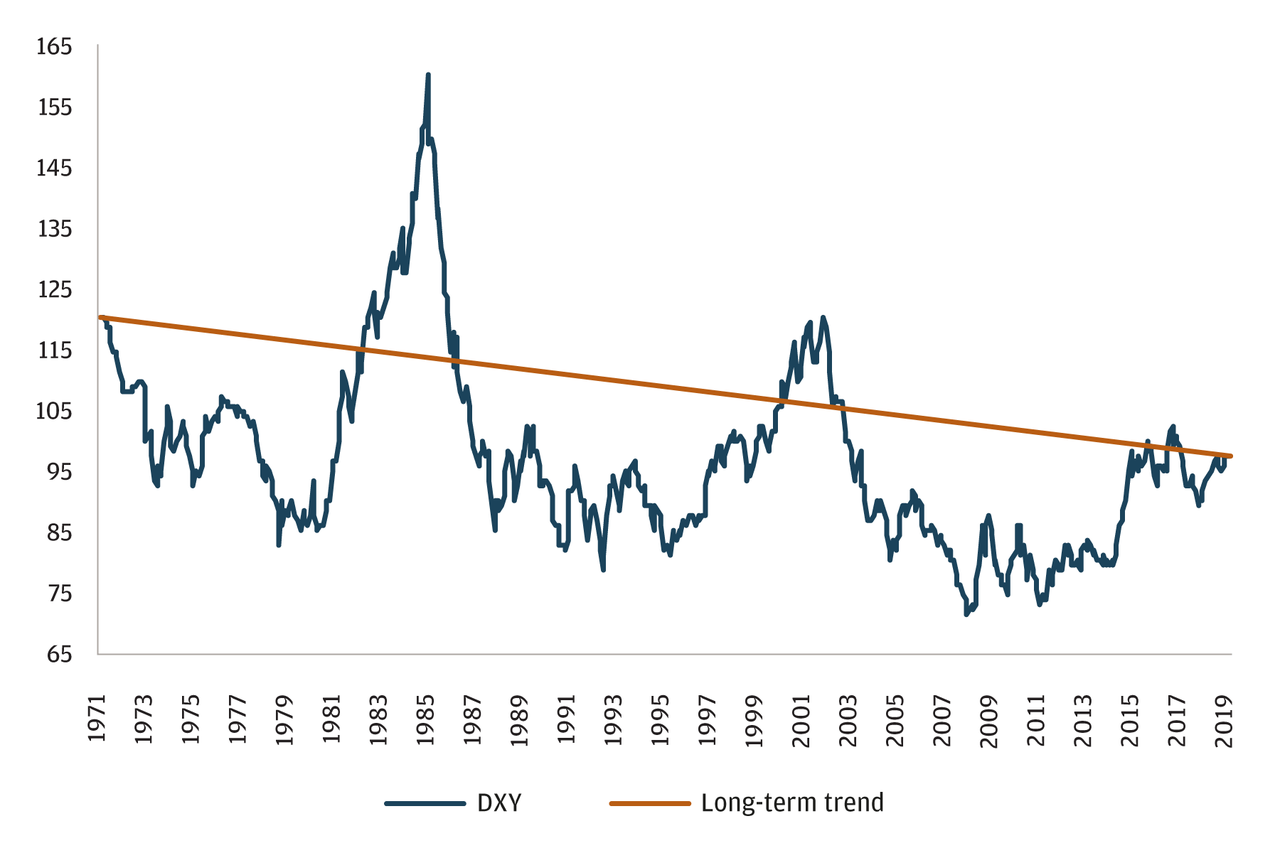

We believe we are at an important juncture. On a real basis, the dollar stands currently more than 10% above its long-term average and on a nominal basis has actually been trending lower for 50 years (see chart below).

Given the persistent—and rising—deficits in the United States (in both fiscal and trade), we believe the U.S. dollar could become vulnerable to a loss of value relative to a more diversified basket of currencies, including gold. As we scan client portfolios, we see that many of them have far more U.S. dollar exposure than we feel is prudent. At this stage of the economic cycle, we believe this exposure should be more diversified. In many cases, our recommendation would likely be to place a higher weighting on other G10 currencies, currencies in Asia and gold (see chart).

FX exposure

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2y7Qlit Tyler Durden