Authored by Steve Englander via Standard Chartered,

Whoever can surprise well must conquer – John Paul Jones

There is much discussion, but also confusion, about the impact of central bank surprises on asset markets and economic activity. We argue:

-

In the current cycle, it makes little difference to asset prices and activity whether the Fed cuts 50bps in July (unlikely) or 25bps in July and 25bps in September or October. The same holds for the ECB moving in July or September (see FOMC – dovish tilt, ECB – Easy does it).

-

Lower-for-longer rates matter more than deep but short-lived cuts, subject to the broad limits of monetary policy effectiveness discussed in Japanification.

-

Moving faster than market pricing could provide a signal that boosts confidence in the easing narrative, but the impact is likely to be shorter-term relative to a slightly slower pace of policy moves.

-

The economic impact comes from the cumulative easing that households and businesses experience, not surprises around central bank meetings.

-

Stronger activity data in July may be due to easing priced in January, but may also reflect underlying strength in the economy.

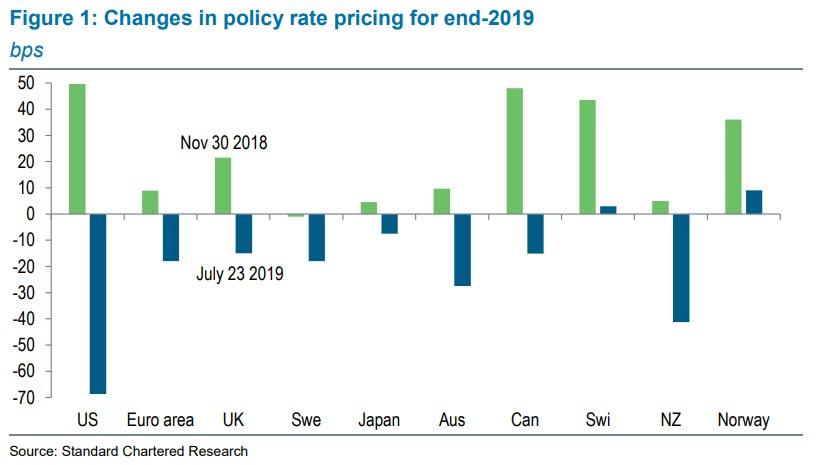

Money markets now price in an average of about 20bps of cuts in G10 economies for the rest of this year, with 69bps for the US (105bps by end-2020). Since end-November 2018, expected policy rates for end-2019 have dropped 42.5bps (Figure 1). On the fixed income side, market pricing for 2Y USTs around year-end is 1.75%, versus our forecast of 1.65%; for 10Y USTs, market pricing is 2.10% versus our 1.75% forecast. The low for fed funds futures is 1.35% for early 2021 contracts.

There is much discussion among investors about the asset-market and economic implications of meeting, beating and missing expectations of central bank easing. Most central banks have not pushed back against market pricing, and some have tacitly or explicitly encouraged such pricing. Money-market repricing of future easing should affect liquid currency, fixed income, equity and commodity markets very quickly, if not immediately.

The economic impact of this repricing occurs over time, not immediately. There is considerable uncertainty over how fast the impact is felt; an easing of financial conditions in January could have an impact by July, but might not. Investors must assess whether solid activity will cause the central bank to rein in expectations or vindicate them. Both asset-market and economic responses will be driven by the full path of expected rates changes. The ultimate impact will be driven by the cumulative expected move in rates and the duration of the move.

This pricing does not necessarily have positive implications for all asset markets. If the S&P is slightly above 3,000 when the fed funds rate is expected to drop almost 100bps over the next year, the macro justification for further gains seems limited. Positive surprises are possible, for example, if the US-China trade talks produce a stellar deal, but risks will almost always be two-sided relative to market pricing.

Investors look at the effects of lagged tightening and easing

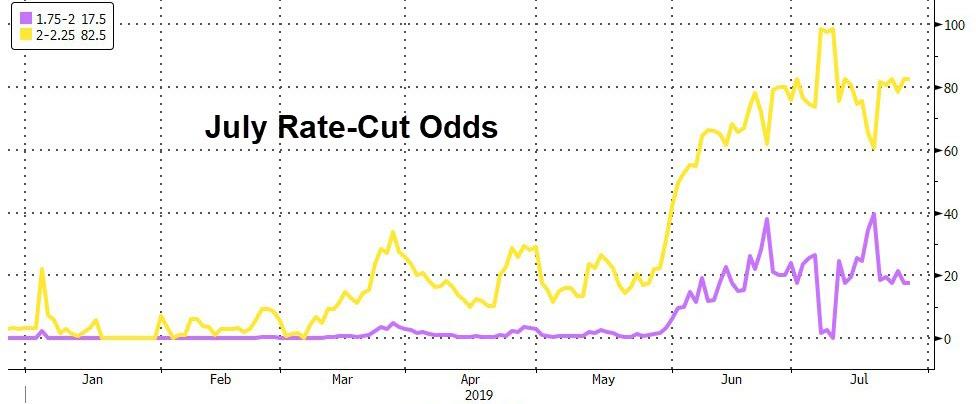

Modern financial theory starts from the view that liquid markets integrate surprises quickly. If the Fed or another central bank announces a policy shift, the impact of the shift in asset prices will likely be felt quickly. When investors shift from seeing a 50% or more chance of 50bps of cuts to near certainty of 25bps (as occurred over 18-19 July), bond yields, equity prices and currencies factor in the perceived policy shift almost immediately.

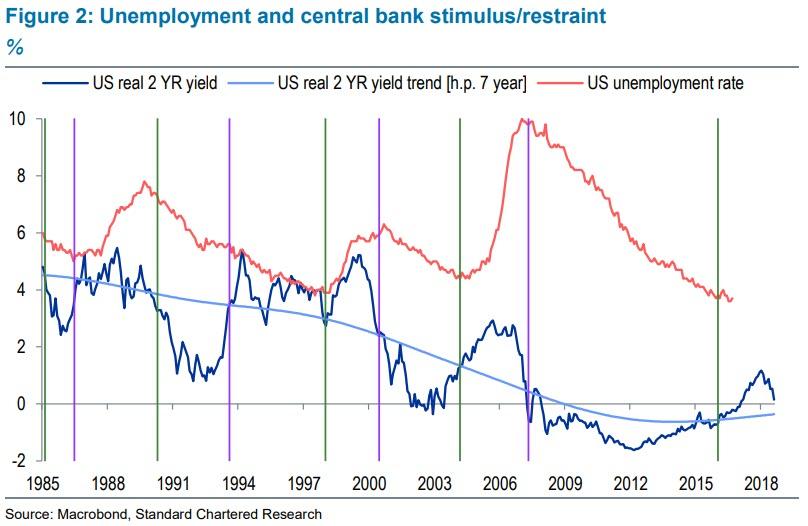

The perceived policy shift will probably not affect economic prospects very rapidly. The way most models present it, the degree of monetary stimulus can roughly be measured by how long rates spend below neutral and how low they go. Figure 2 shows the US unemployment rate (UR), real 2Y UST yields (measured by subtracting lagged two-year core inflation from nominal 2Y UST yields), and the detrended value of the real 2Y yield. The UR leads by 24 months, so today’s UR corresponds to the real 2Y yield of 24 months ago.

We use the trend 2Y UST real yield as a rough proxy for the long-term equilibrium real yield. The gap between actual 2Y UST real yields and the trend value can be seen as stimulus if real yields are below the trend; or as restraint if real yields are higher. In technical terms, most models would say that the degree of economic stimulus would be measured by the integral between actual and neutral rates. The beginnings and ends of such periods of stimulus and contraction are indicated in Figure 2 by the vertical lines, with green indicating the beginning of stimulus and purple the end.

The correspondence between episodes of a falling and rising UR and our stimulus/contraction measures is striking , especially considering the simplicity of our measure of policy stimulus and contraction. We think that our calculations illustrate these broader points:

-

The measure of stimulus is how far real rates are from equilibrium and how long this deviation persists.

-

A policy surprise can intensify or slow the pace of easing, but unless it becomes tightening, it would not flip the economy into recession.

-

The long and variable lags from rates to activity mean that investors and central banks are always guessing how much fuel there is in the stimulus tank – they may not know for months.

-

In the current context, we do not necessarily know if the economy is responding to the tightening that occurred in 2017-18 or the more recent easing. Calculation of equilibrium rates is more reliable towards the middle of the sample than right at the end.

-

The fact that the economy looks somewhat stronger now may reflect the easing that is now priced in, or it may mean that the equilibrium real interest rate is higher than we thought. We probably will not know for a while, but as long as inflation is contained, investors will likely keep easing expectations in place.

How bound are central banks by market pricing?

Investors have to consider the risk that central banks will disagree with market pricing of future rate cuts. Markets will see a central bank as confirming market pricing if it does not use opportunities to push back against that pricing. This can be done at meetings or in speeches before meetings.

Even if central bank officials do not want to pre-empt future central bank decisions, they can signal concerns around market pricing. The risk if they do not provide this signal is unnecessary asset-market volatility and possibly economic volatility, although the central bank would probably need to leave the mispricing in place for an extended period for the economy to be affected. Investors will see silence as central bank consent as long as future data releases are in line with market expectations at the time when implied consent was given.

Central banks may understate their concerns about future activity on the view that too much pessimism will risk pushing markets – and even household and business expectations – in an overly negative direction. Moreover, if they say ‘we think the economy is likely to tank’, they have an imperative to move quickly and sharply. To avoid this situation, they will hint at risks of future weakness, and hope that market participants take the hint.

Central banks also have a practical motivation not to let excessive priced-in easing or tightening persist. The risk is that such pricing will affect economic data over time, and create confusion over whether the economy was responding to the priced-in easing or underlying strength.

The market risk on the other side is that central banks always convey their views in conditional terms. This conditionality is often not emphasised because the central bank wants the market to react to its forward guidance, and heavy conditionality would limit the response. But a close reading of central bank comments often implies expectations of data outcomes that must be confirmed in order for the central bank to act. Confidence that ‘insurance cuts’ will remain in place requires that the fears that drove the need for insurance are realised. Central banks can fall back on this conditionality as needed, and market participants have to factor this risk into asset pricing.

Is one big surprise more powerful than a series of small surprises?

There is much speculation that just meeting market expectations will be a disappointment to investors or mitigate the impact of easing. The need for a policy surprise was discussed frequently when the market was debating whether the Fed’s July meeting would deliver 25bps or 50bps of cuts.

We want to be careful to make apples-to-apples comparisons. There is not much theoretical or empirical analysis to indicate that one surprise 50bps cut is significantly more powerful than two surprise 25bps cuts reasonably close together. This would require a non-linear response by asset markets or the economy, and such non-linearities are often hard to justify or establish empirically. So 50bps achieves easing slightly faster, but that is likely to make only a trivial difference to the ultimate outcome.

Similarly, the drop in expected policy rates (Figure 1) has already affected asset prices, and is likely to affect activity over time. The cuts that are priced in represent a series of surprises building since December. The drop relates partly to Fed statements or actions, and partly to market views on how the global and domestic economies and policy are likely to evolve. The asset-price implications of actual Fed easing are unlikely to differ much from the implications of market expectations of easing, provided both are driven by the same reading of data.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/32XuzfF Tyler Durden