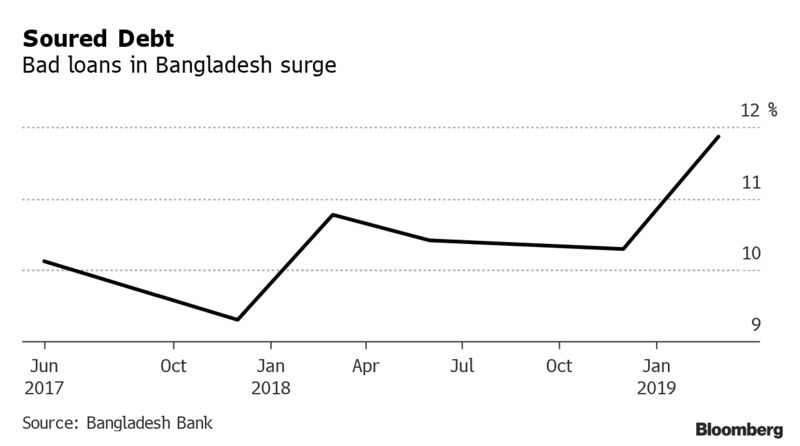

Bangladesh’s Central Bank in May introduced an amnesty program that allowed delinquent borrowers to make a small upfront payment and then pay off the rest of their debt over 10 years at favorable interest rates, according to Bloomberg.

However, the plan also triggered a rush by healthy companies to reschedule debt on the same terms which, in turn, now threatens to overwhelm the country’s banks.

The program is also seen as encouraging those with debt to default. Big surprise, right?

Anis A. Khan, managing director of Dhaka-based Mutual Trust Bank Ltd. said:

“I’m traumatized by non-performing loans. Borrowers have been using every excuse they can find — from a death in the family to political uncertainty — to try to get onto the central bank program.”

The initiative is available to borrowers until September 7 and created a “perverse incentive” to default. Now, the country is expecting that nonperforming loans may rise significantly from 11.9% in March as a result of the program.

The upfront payment was lowered to 2% from 10% for those who are defaulting for the first time. The maximum interest rate over the next 10 years was set at 9%, even if borrowers were paying as high as 15% previously.

And like all other great “Band-Aid” fixes to debt problems, the initiative has backfired: it has created a sense among Bangladeshi companies that people can get away without paying back their loans. That, in turn, poses a threat to the wider economy and a banking system that is already overwhelmed with defaults.

The central bank, meanwhile, says that the policy will help revive lending growth in an economy that is dependent on attracting investment to sustain growth. Asian Development Bank predicts that the country’s economy will expand 8% over the next two years.

Shitangshu Kumar Sur Chowdhury, banking reforms adviser at Bangladesh Bank said:

“It was necessary to take some remedial measures to bail out the defaulters. It’s not flawless, just like any other policy, but it has more merits than demerits.”

But Chowdhury also acknowledges that the policy creates moral hazard:

“That’s why we kept it open only for a short period to minimize it.”

At places like Mutual Trust Bank, gross bad loans climbed to more than 6% in June from 4.3% two years ago and are slated to rise further.

Mattias Martinsson, chief investment officer at Stockholm-based Tundra Fonder AB concluded:

“One of our concerns in Bangladesh over the last five years has been poor transparency in the banking sector. The changes will obviously not stimulate further investments.”

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2ZirVTr Tyler Durden