Most of last Friday’s Jackson Hole focus was on Powell, but what Standard Chartered’s chief FX strategist, Steven Englander was struck by, was the apparent consensus among JH participants, that US rates and USD were too high, surprisingly, but hardly consciously in line with President Trump’s views. And while Englander does not see a direct line from such intellectual consensus to a weaker USD, he would not rule out that weaker USD somehow ends up as the long-term outcome.

Below we recap some of the key points from Englander’s take on the “modest proposal” to reduce the USD’s role in reserves.

As the FX strategist notes, a strange convergence of views emerged between President Trump and Jackson Hole (JH) participants. The president feels that lower US rates and a weaker USD would be good for the US. Participants at Jackson Hole suggested that a weaker USD and lower US interest rates would be good for the world. The similarity can be extended in that the president sees higher US rates as having choked off growth in the US economy, while the JH crowd sees higher US rates and a stronger USD as having choked off growth abroad through the risk-premium channel.

Of course, if that was all there is to the debate, then we would have a new Plaza Accord as soon as this weekend: after all, “everyone agrees” that the dollar is strong, right? Then just agree to devalue it.

Alas it never is quite that simple.

As Englander expands, at JH the discussion of the negative impact of USD strength focused on emerging market (EM) economies. A weaker USD against developed market (DM) currencies is probably necessary and sufficient to weaken the USD against EM currencies, but DM assets don’t face the same risk premium as EM assets when their currencies depreciate. Currency weakness for DM economies does not carry the same risk premium as for EM economies. In other words, Europeans may not mind a weaker USD, as long as it doesn’t come with a stronger EUR (which it inevitably will).

The bigger point, of course, is that the extensive discussion of the USD, US rates and risk premia abroad establishes an analytical basis for a weak USD as a global policy. Indeed, as we repeatedly noted in the past week, outgoing Bank of England Governor Carney argued for an alternative reserve asset to the USD. It is too early to tell whether monetary easing in the US and fiscal stimulus in the EU can both stimulate each region and give the world the combination of low rates and weaker US dollar that are needed.

Another reason to replace the USD as the global reserve currency

For those who missed it, Carney gave “a surprisingly pointed talk on the international monetary and financial system (IMFS), in which he argued for dramatic long-term changes. In particular, he felt that the USD’s pre-eminence in international financial transactions was disproportionate to the US’ importance in production and trade” as Englander recaps. Still, there is no guarantee that US monetary policy makers will adequately take into account spillover into EM economies. The other issue is the pro-cyclicality of capital flows into EM economies, which means that a tightening of DM financial conditions drives a withdrawal of capital from EM markets.

None of this should be new.

The surprise was his long-term recommendation that the USD-centric system of global finance be replaced by a multi-polar system, arguing that a system of “multiple reserve currencies would increase the supply of safe assets”. In consequence, “the safety premium they [reserve currencies] receive should fall” and ”reduce the fragilities in the system, and increase the sustainability of capital flows”. As Englander continues, noting that transactions are increasingly online and through electronic payments, Carney went on to argue for central bank digital currencies as a new reserve asset, analogous to proposed new private-sector “payments infrastructure … fully backed by reserve assets in a basket of currencies”.

He certainly has it in for the USD:

“The IMFS … is also encouraging protectionist and populist policies which are exacerbating the situation. This combination reduces the rate of global potential growth, increases its downside skew, and bolsters the likelihood of an extreme downside event (a fatter left tail). … such a change in the distribution of economic outcomes reduces the global equilibrium rate of interest. Past instances of very low rates have tended to coincide with high risk events such as wars, financial crises, and breaks in the monetary regime.”

The punchline in Carney’s speech: the proposal for a Global Hegemonic Currency (GHC) to “dampen the domineering influence of the US dollar on global trade” to “help reduce the volatility of capital flows to EMEs”. EM countries would diversify away from the USD, reducing risk. As this digital reserve currency was increasingly used in trade and finance, the impact of US shocks and USD shocks would become less important in EM asset markets. He seems to want the GHC to replace rather than augment USD as a reserve asset. What was not said that such a transfer of reserve status from a central bank-backed currency to a digital/crypto currency is a tacit admission that central banks are now powerless, and the transformation is one of necessity as the old, fiat model begins to fall apart (of course, none of this could be verbalized at a central banker convention).

As Englander correctly notes, Carney’s proposal is certainly audacious, and “would appeal to the IMF, whose role in international financial policy would be increased. The proposal would also appeal to countries that want to see the role of the USD in international finance reduced for political reasons. It is less clear whether EM countries would prefer a new reserve asset or more ready availability of the old one.”

Then again, as Carney puts his proposal, it may not be very enticing to US policy makers (Rabobank’s Michael Every said that the US would not relinquish reserve status without a fight). One important consequence would be long-term diversification away from the USD in reserve portfolios and private-sector balances. A smaller role for the USD in international trade and finance would mean that private-sector businesses would need lower transaction balances denominated in USD. All of these factors would likely push the USD lower, not just cyclically, but structurally as well, and as Std Chartered summarizes, “the US would give up its free lunch from global reserves demand of about USD 10-15bn per year. It is also possible that US rates would be higher because of lower demand for USD assets from abroad.”

So will it work?

Some, as Englander saud, “would label the proposal as a bunch of buzzwords stretching from Jackson Hole to Washington, but it is worth looking closely at the proposal and flagging where more work has to be done to establish whether the SHC has the intended properties.” The FX strategist sees a couple of issues:

- The proposal looks a lot like a digital version of the Special Drawing Right (SDR) which has been around for fifty years. Interest in the SDR perks up every decade or so when the basket is reconfigured and then disappears. Private-sector participants can borrow and lend in SDRs if they like but there does not seem to be much demand for such products, despite their diversification advantages.

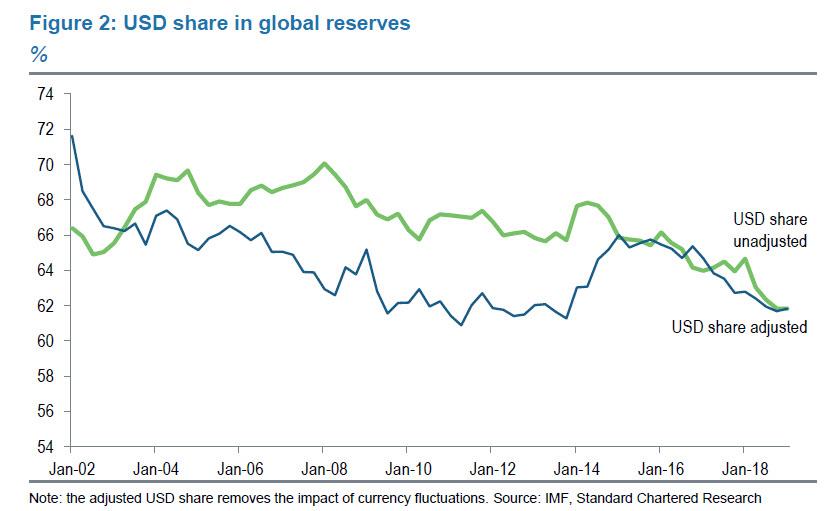

- Carney emphasizes the disadvantages to the USD-based system for the EM world, but does not discuss the liquidity, scale and networking economies that might accrue to having a single currency as the premier accepted global reserve asset. Both the pros and the cons to having a multipolar as opposed to hegemonic reserve system are speculative. Most discussions of the history of reserves, including Carney’s, emphasise that there is usually one dominant reserve currency at a time. There have been episodes of USD strength over the last 15 years that have not been used for shrinking the USD share in reserves (Figure 2), so holding dollars must be voluntary to some degree.

- The incumbency advantage of the dominant reserve currency means that it may be an expensive proposition to establish an alternative, with uncertain success.

- Correlations among asset prices often go to one when there is a financial crisis, eliminating the key advantage of the SHC. If reserves consisted of a broader set of DM currencies that are viewed as safer than EM currencies, we would still see EM under pressure if a big enough shock hit. Carney has faith that the existence of the diversified alternative asset will be enough to keep DM money in EM.

- The set of circumstances where SHC outperforms USD may be quite narrow. The shocks have to be moderate rather than acute (to avoid correlations going to one) and have to be worse outside the US than inside. This fits where we are now but may not match future scenarios.

- The key question may be whether there is a mechanism to fill the EM funding gap when a shock hits. If there is such a mechanism, it may not make much difference if the funding is in USD or SHC. If there is no such mechanism, it may not make much difference what the nature of the reserve currency is.

- Fiscal expansion may be the biggest ‘favor’ that DM countries can do for EM. Fiscal expansion in DM would both give a boost to local and global demand and increase the supply of safe DM assets, reducing their scarcity.

The bottom line, at least to Std Chartered’s FX team is the intellectual consensus at Jackson Hole that lower US rates and a weaker USD were desirable. Not all proposal solutions look practical to, but the takeaway is that there is a growing consensus that a weaker US dollar would be a good idea, and policy makers are beginning to look for a way to implement it.

In other words, instead of a sharp drop in the yuan, don’t be surprised to wake up one morning and see your favorite dollar index devalued by about 10% against all of its currency pairs.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2ztqZfF Tyler Durden