“The Fed Was Suddenly Facing Multiple LTCMs”: BIS Offers A Stunning Explanation Of What Really Happened On Repocalypse Day

About a month ago, we first laid out how the sequence of liquidity-shrinking events that started about a year ago, and which starred the largest US commercial bank, JPMorgan, ultimately culminated with the mid-September repo explosion. Specifically we showed how JPM’s drain of liquidity via Money Markets and reserves parked at the Fed may have prompted the September repo crisis and subsequent launch of “Not QE” by the Fed in order to reduce its at risk capital and potentially lower its G-SIB charge – currently the highest of all major US banks.

Shortly thereafter, the FT was kind enough to provide confirmation that the biggest US bank had been quietly rotating out of cash, while repositioning its balance sheet in a major way, pushing more than $130bn of excess cash away from reserves in the process significantly tightening overall liquidity in the interbank market. We learned that the bulk of this money was allocated to long-dated bonds while cutting the amount of loans it holds, in what the FT dubbed was a “major shift in how the largest US bank by assets manages its enormous balance sheet.”

The moves saw the bank’s bond portfolio soar by 50%, and were prompted by capital rules that treated loans as riskier than bonds. And since JPM has been aggressively returning billions of dollars to shareholders in dividends and share buybacks each year, JPMorgan had far less room than most rivals to hold riskier assets, explaining its substantially higher G-SIB surcharge, which indicated that the Fed currently perceives JPM as the riskiest US bank for a variety of reasons.

An executive at a large institutional investor told the FT that what JPM did “is incredible”, adding that “the scale of what JPMorgan is doing is mind-boggling . . . migrating out of cash into securities while loans are flat.”

The dramatic change, which occurred gradually over the year, and which may have catalyzed the spike in repo rates in September, was first flagged by JPMorgan at an investor event back in February. Then CFO Marianne Lake said that, after years of industry-leading loan growth, “we have to recognize the reality of the capital regime that we live in”.

About half a year later, the rest of the world did too when the overnight general collateral rate briefly did something nobody had ever expected it to do, when it exploded from 2% to about 10% in minutes, an absolutely unprecedented move, and certainly one that was seen as impossible in a world with an ocean of roughly $1.3 trillion in reserves floating around.

While readers can catch up on the nuances of what JPM did in our prior post, the bottom line is that the execution of the plan was flawless, and as we said at the start of November, “to ensure that JPM’s tens of billions in buybacks and dividends continue flowing smoothly and enriching the company’s shareholders, Jamie Dimon may have held the entire US financial system hostage, forcing the Fed’s hand to restart “Not QE.”

To be sure, the mere hint that the September repocalypse was an orchestrated event (in some ways similar to the Lehman failure which ushered in QE1), meant to extract liquidity concessions out of the Fed (NOT QE or QE 4 depending on one’s semantic persuasion) and enrich a handful of bank executives was scandalous enough, and could not be left unaddressed, especially since fears about repo market stability are once again growing now that just three weeks are left until the traditionally liquidity sapping year-end moment.

Well, to address just that, and to provide a fascinating new perspective on what may have catalyzed the Sept 17 events, which were “this close” from triggering an LTCM-like cascade within the market, the Bank of International Settlements – the central banks’ central bank – today published a paper as part of its quarterly review, titled “September stress in dollar repo markets: passing or structural?“, which “found” several things that we already knew – the September event was not a one-time, passing shock to the repo system contrary to what a handful of “know it all” fintwit accounts claimed but is a structural problem with US liquidity plumbing; it also found that just four commercial banks are now the dominant marginal lenders in the US repo market (and where just one, JPMorgan saw its liquidity provisioning collapse in the course of 2019 as noted above). However, in a novel twist, the BIS also found that hedge funds exacerbated the turmoil in the repo market with their thirst for borrowing cash to juice up returns on their trades.

Here is what the BIS said:

US repo markets currently rely heavily on four banks as marginal lenders. As the composition of their liquid assets became more skewed towards US Treasuries, their ability to supply funding at short notice in repo markets was diminished. At the same time, increased demand for funding from leveraged financial institutions (eg hedge funds) via Treasury repos appears to have compounded the strains of the temporary factors.

The BIS also echoed the now widely accepted justification for the Fed’s recent decision to resume POMOs, saying that it is also possible that the “low” level of reserves, and the financial system’s inability to revert back to normalcy, may also have catalyzed the repo move:

Finally, the stress may have been amplified in part by hysteresis effects brought about by a long period of abundant reserves, owing to the Federal Reserve’s large-scale asset purchases.

Here, one can argue that the implication of that sentence alone are staggering, as they confirm what most have already known: there is no way the financial system can ever return to a world without trillions and trillions in “excess reserves.” For the BIS to make that admission is rather striking, as it underscores that the world will never again be able to exist in a regime in which central banks do not constantly create money (or reserves) out of thin air to prop up asset prices.

Yet while that topic alone is worth a post or several thousand (we have certainly beaten this particular horse to death over the past decade), the core focus of the BIS paper in question was to identify more “usual suspects” on which to blame both the recent, and all future – because these are only just starting – repo crises.

Enter hedge funds.

First, a quick detour: when it comes to potentially systemic factors affecting the US financial system, none have more importance and gravity than the repo market. As the BIS writes, “Repo markets redistribute liquidity between financial institutions: not only banks (as is the case with the federal funds market), but also insurance companies, asset managers, money market funds and other institutional investors. In so doing, they help other financial markets to function smoothly. Thus, any sustained disruption in this market, with daily turnover in the US market of about $1 trillion, could quickly ripple through the financial system. The freezing-up of repo markets in late 2008 was one of the most damaging aspects of the Great Financial Crisis (GFC).“

Keeping the above in mind, here’s a quick remind of what happened on September 17: the secured overnight funding rate (SOFR), the new, repo market-based, US dollar overnight reference rate which is supposed to replace over the next two years – more than doubled, and the intraday range jumped to about 700 basis points when repo rates typically fluctuate in an intraday range of 10 basis points, or at most 20 basis points. Intraday volatility in the federal funds rate exploded. Hot take explanations for this move include a due date for US corporate taxes and a large settlement of US Treasury securities. However, as first we, and then now the BIS admits, “none of these temporary factors can fully explain the exceptional jump in repo rate.”

Ok, but all of the above was known before. What’s new about the BIS’ paper?

Well, in the aftermath of Sept 17, attention focused on the role played by banks, which had become reluctant to lend cash into the market despite the higher interest rates on offer. And while the BIS acknowledged that the pullback by banks, especially the “Big Four”, was a significant factor in the shake-up,

… it also said that cash-hungry hedge funds had amplified the dislocation.

“High demand for secured (repo) funding from non-financial institutions, such as hedge funds heavily engaged in leveraging up relative value trades,” was a key factor behind the chaos, said Claudio Borio, head of the monetary and economic department at the BIS.

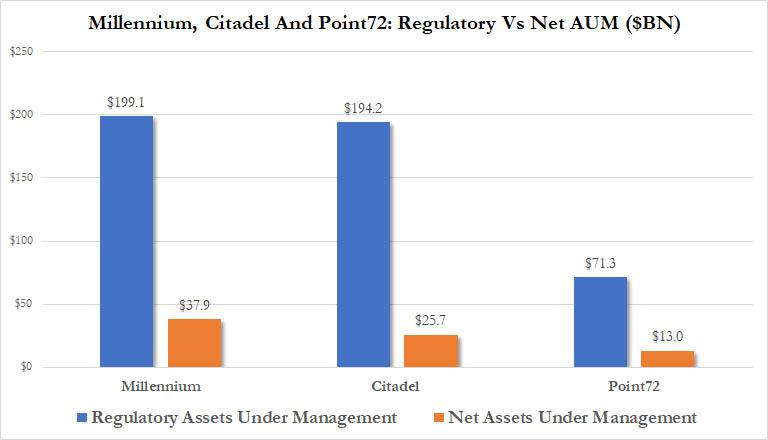

The BIS’s finding is novel, and surprising, as they highlight the “growing clout of hedge funds in the repo market” according to the FT, which notes something we pointed out one year ago: hedge funds such as Millennium, Citadel and Point 72 are not only active in the repo market, they are also the most heavily leveraged multi-strat funds in the world, taking something like $20-$30 billion in net AUM and levering it up to $200 billion. They achieve said leverage using repo.

One increasingly popular hedge fund strategy involves buying US Treasuries while selling equivalent derivatives contracts, such as interest rate futures, and pocketing the arb, or difference in price between the two.

While on its own this trade is not very profitable, given the close relationship in price between the two sides of the trade. But as LTCM knows too well, that’s what leverage is for. Lots and lots and lots of leverage.

As the FT notes, people active in the short-term borrowing markets say that to fire up returns, “some hedge funds take the Treasury security they have just bought and use it to secure cash loans in the repo market. They then use this fresh cash to increase the size of the trade, repeating the process over and over and ratcheting up the potential returns.“

In short, and as shown in the chart above, some of the world’s biggest hedge funds are active in the repo market to boost their returns. The problem is what happens when repo rates get unhinged as happened on September 17: for the best example of how market players react when their underlying correlations go tilt, look no further than what happened to LTCM in 1998.

This also explains why the Fed panicked in response to the GC repo rate blowing out to 10% on Sept 17, and instantly implemented repos as well as rushed to launch QE 4: not only was Fed Chair Powell facing an LTCM like situation, but because the repo-funded arb was (ab)used by most multi-strat funds, the Federal Reserve was suddenly facing a constellation of multiple LTCM blow-ups that could have started an avalanche that would have resulted in trillions of assets being forcefully liquidated as a tsunami of margin calls hit the hedge funds world.

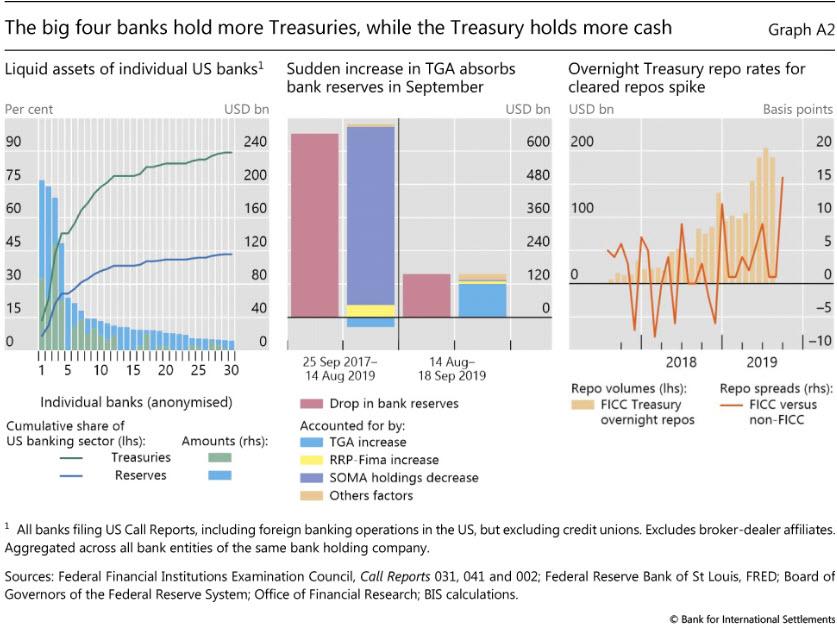

Here it is the Big Four banks that were once again instrumental in allowing this arb to emerge in the first place. As the BIS notes, “concurrent with the growing role of the largest four banks in the repo market, their liquid asset holdings have become increasingly skewed towards US Treasuries, much more so than for the other, smaller banks. (chart below, right-hand panel). As of the second quarter of 2019, the big four banks alone accounted for more than 50% of the total Treasury securities held by banks in the United States – the largest 30 banks held about 90% (chart below, left-hand panel). At the same time, the four largest banks held only about 25% of reserves (ie funding that they could supply at short notice in repo markets).

Ironically, for years this “arb” strategy was once popular among the dealer banks themselves, but higher capital charges since the financial crisis led to their displacement by hedge funds, which have more ability to take on risk.

This is how the BIS explains, in not so many words, how the financial system came close to the verge of collapse on September 17:

Shifts in repo borrowing and lending by non-bank participants may have also played a role in the repo rate spike. Market commentary suggests that, in preceding quarters, leveraged players (eg hedge funds) were increasing their demand for Treasury repos to fund arbitrage trades between cash bonds and derivatives. Since 2017, MMFs have been lending to a broader range of repo counterparties, including hedge funds, potentially obtaining higher returns. These transactions are cleared by the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC), with a dealer sponsor (usually a bank or broker-dealer) taking on the credit risk. The resulting remarkable rise in FICC-cleared repos indirectly connected these players. During September, however, quantities dropped and rates rose, suggesting a reluctance, also on the part of MMFs, to lend into these markets (Graph A.2, right-hand panel). Market intelligence suggests MMFs were concerned by potential large redemptions given strong prior inflows. Counterparty exposure limits may have contributed to the drop in quantities, as these repos now account for almost 20% of the total provided by MMFs.

What this means is that contrary to our initial take that banks were pulling from the repo market due to counterparty fears about other banks, they were instead spooked over exposure by other hedge funds, who have become the dominant marginal- and completely unregulated – repo counterparty to liquidity lending banks; without said liquidity, massive hedge fund regulatory leverage such as that shown above would become effectively impossible.

Meanwhile, as banks pulled back from the repo market amid their “reluctance” to lend to these markets amid “concerns for large redemptions”, hedge funds have sought cash from new sources, such as non-bank dealers or through a platform run by the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation that gives them access to cash from money market funds and other lenders. As a reminder, the “hail mary” thesis of the uber bearish CIO of Horseman Global, Russel Clark, is that clearinghouses will collapse as liquidity is drained from the market:

LCH claim to have done a quadrillion of compression trades or netting in the last year, this is more than twice the notional of all outstanding interest rate derivatives.

If initial margins rise significantly, the only assets that will see a bid will be cash, US treasuries, JGBs, Bunds, Yen and Swiss Franc. Everything else will likely face selling pressure. If a major clearinghouse should fail due to two counterparties failing, then many centrally cleared hedges will also fail. If this happens, you will not receive the cash from your bearish hedge, as the counterparty has gone bust, and the clearinghouse needs to pay from its own capital or even get be recapitalised itself.

The growing significance of these new cash sources “can result in unfamiliar market dynamics“, said BIS’ Claudio Borio. Dynamics such as the one where impossible moves such as repo rates exploding from 2% to 10% in seconds become a daily occurence.

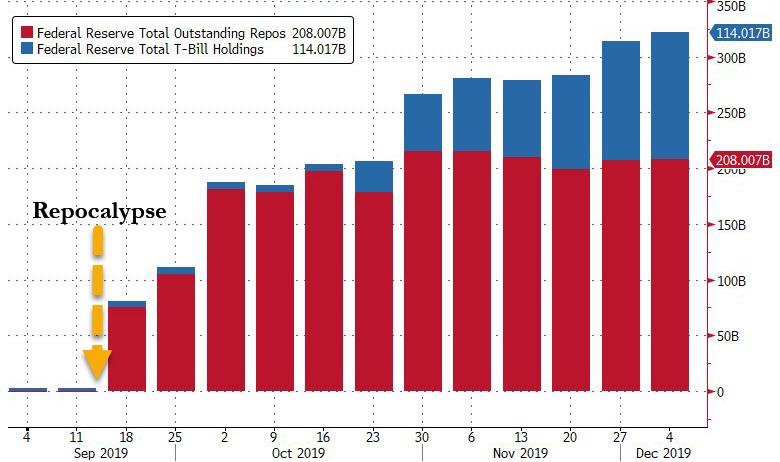

So where does that leave us? Well, as the BIS concludes, since 17 September, “the Federal Reserve has taken various measures to supply more reserves and alleviate repo market pressures. These operations were expanded in scope to term repos (of two to six weeks) and increased in size and time horizon (at least through January 2020). The Federal Reserve further announced on 11 October the purchase of Treasury bills at an initial pace of $60 billion per month to offset the increase in non-reserve liabilities (eg the TGA). These ongoing operations have calmed markets.”

We have covered all these “mitigating events”, and the problem is that even though the Fed has now injected $208BN in liquidity via overnight and term repos, and $114BN via permanent T-Bill purchases, or POMO (i.e. “Not QE”), expanding the Fed’s balance sheet by $322 billion, the repo market still remains broken…

… and the world may find just how broken it is as soon as December 31, when the next repocalypse event is tentatively scheduled to strike. The big question is whether the world’s mega hedge funds, the Millenniums, the Citadels, the Point72s afraid they will lose access to the precious repo funding that permits them to lever up as much as 10x, will sharply deleverage ahead of this event, in the process sending risk prices tumbling and precipitating the next market crash.

But don’t take our word: here again is the top financial expert at the BIS, Claudio Borio, warning that that September’s dislocation suggests that such repo “events” are only just starting and the repo markets “may again find themselves in the eye of the storm should financial stress arise at some point”, a point which as the Fed recently revealed in its October FOMC Minutes could take place as soon as year-end.

Tyler Durden

Sun, 12/08/2019 – 21:33

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2PuwoL1 Tyler Durden