John Solomon Slams Adam Schiff’s “Surveillance State” Abuse: “Chilling Effect On Press Freedom”

The Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Domestic Investigations and Operations Guide, the bible for agents, has long recognized that journalists, the clergy and lawyers deserve special protections because of the constitutional implications of investigating their work. Penitents who confess to a priest, sources who provide confidential information to a reporter, and clients who seek advice from counsel are assumed to be protected by a high bar of privacy, which must be weighed against the state’s interests in investigating matters or subpoenaing records. Judges and members of Congress also fall into a special FBI category because of the Constitution’s separation of powers.

The FBI and Justice Department have therefore created specific rules governing agents’ actions involving special-circumstances professionals, which include high-level approval and review. There are also special rules for subpoenaing journalists.

If the executive branch, and by extension the courts that enforce these privacy protections, observe the need for such sensitivity, it seems reasonable that Congress should have similar guardrails ensuring that the powers of the state are equally and fairly applied.

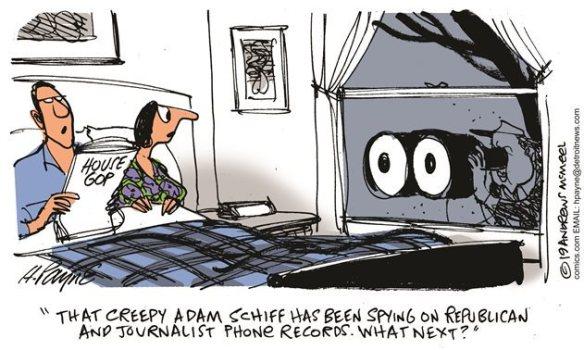

House Intelligence Committee Chairman Adam Schiff apparently doesn’t see things that way.

His committee secretly authorized subpoenas to AT&T earlier this year for the phone records of President Trump’s personal attorney, Rudy Giuliani, and an associate. He then arbitrarily extracted information about certain private calls and made them public.

Many of the calls Mr. Schiff chose to publicize fell into the special-circumstances categories: a fellow member of Congress ( Rep. Devin Nunes, the Intelligence Committee’s ranking Republican), two lawyers (Mr. Giuliani and fellow Trump lawyer Jay Sekulow ) and a journalist (me).

More alarming, the released call records involve figures who have sometimes criticized or clashed with Mr. Schiff. I wrote a story raising questions about his contacts with Fusion GPS founder Glenn Simpson, a key figure in the Russia probe, that brought the California Democrat unwelcome scrutiny. Mr. Nunes has been one of Mr. Schiff’s main Republican antagonists, helping to prove that the exaggerated claims of Trump-Russia election collusion were unsubstantiated. Messrs. Sekulow and Giuliani represent Mr. Trump, who is Mr. Schiff’s impeachment target.

Mr. Schiff’s actions in obtaining and publicizing private phone records trampled the attorney-client privilege of Mr. Trump and his lawyers. It intruded on my First Amendment rights to interview and contact figures like Mr. Giuliani and the Ukrainian-American businessman Lev Parnas without fear of having the dates, times and length of private conversation disclosed to the public.

Contrary to Mr. Schiff’s defense that he was simply serving the investigative interest of Congress, the release of the phone records served much more to punish people whose work Mr. Schiff found antagonistic than to fulfill an oversight purpose. And it served Congress poorly because it spread false insinuations. Mr. Schiff’s report suggested, for instance, that Mr. Giuliani called the White House to talk to the Office of Management and Budget, implying he might have been trying to help Mr. Trump withhold aid to Ukraine as Democrats allege. The White House says that claim is wrong; the number was a generic phone entry point and no one in OMB talked to Mr. Giuliani.

Likewise, Mr. Schiff published call records between Mr. Giuliani and me and suggested they involved my Ukraine stories. Many contacts I had with Mr. Giuliani involved interviews on the Mueller report and its aftermath or efforts to invite the president’s lawyer on the Hill’s TV show, which I supervised.

Mr. Schiff’s team has tried to minimize the conduct because he never subpoenaed my phone records directly but extracted them from others’ call records. That defense is laughable.

Once a journalist and his calls are made public through the powers of the surveillance state, there is an instant chilling effect on press freedom.

I know this firsthand. In 2001 and 2002, when I was a reporter for the Associated Press, the Justice Department obtained my home phone records and the FBI illegally seized my mail without a warrant in an effort to unmask my sources on federal corruption and stop publication of a story about the government’s counterterrorism failures before 9/11. In the end the FBI returned my reporting records, apologized to me privately, and announced new rules to avoid a repeat for other journalists.

Yet by that time many of my longtime sources had told me they had chosen not to contact me for fear of being detected. Others would only meet in person, concerned that my phones were wiretapped.

Similarly, in the days since Mr. Schiff’s phone-record release, I have had people who openly talked to me on the phone this year suddenly ask to communicate only by encrypted apps. They don’t want their names splashed in the next congressional report. And they fear a bipartisan open season on phone records of political opponents in the future.

Rep. Mike Turner (R., Ohio), a member of the Intelligence Committee, tells me he’s drafting legislation to put guardrails on future congressional subpoenas for phone records. That’s a good start, but more needs to be done sooner.

Mr. Schiff appears to assume that Congress enjoys unlimited investigative powers under the Constitution’s Speech or Debate clause. He does not. I recommend the chairman examine the record in McSurely v. McClellan, a two-decade legal battle that began in 1967 and pitted a powerful committee chairman against a liberal activist couple in Kentucky. It is widely regarded—along with the McCarthy hearings of the 1950s—as one of most egregious episodes of misconduct in the modern history of congressional oversight.

In one of the final appellate decisions in that topsy-turvy case, the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia ruled that Congressional oversight isn’t boundless and that the Speech or Debate Clause has limits. The final paragraph of that ruling derided a “sorry chapter of investigative excess.”

The judges wrote that their decision:

“can only stand as a small reaffirmation of the proposition that there are bounds to the interference that citizens must tolerate from the agents of their government—even when such agents invoke the mighty shield of the Constitution and claim official purpose to their conduct.”

That principle is due for another affirmation.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 12/10/2019 – 08:50

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2RCHZu1 Tyler Durden