Hundreds Of Billions In Gold And Cash Are Quietly Disappearing

Something strange is going on: at the same time that central banks are injecting $100 billion each month in electronic money to crush volatility and ramp markets, a similar amount in hard physical currency and precious metals is literally disappearing.

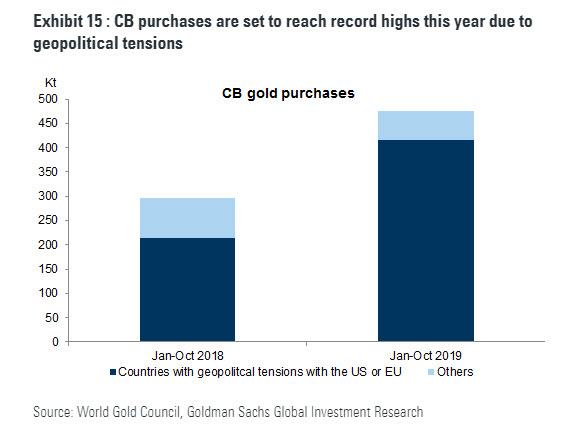

Take gold: as we reported last week, it was none other than Goldman Sachs which recently laid out the case for gold, saying “gold’s strategic case still strong.” One reason for this is that the same central banks that are “full tilt” printing cash, they have also been splurging on gold, and as a result of “geopolitical uncertainty” there has been a record surge in gold demand by central banks themselves. As Goldman notes, “CBs globally have been buying gold at a very strong pace” and “2019 looks to be a record year for CB gold purchases with our target of 750 tonnes combined purchases likely to be met.”

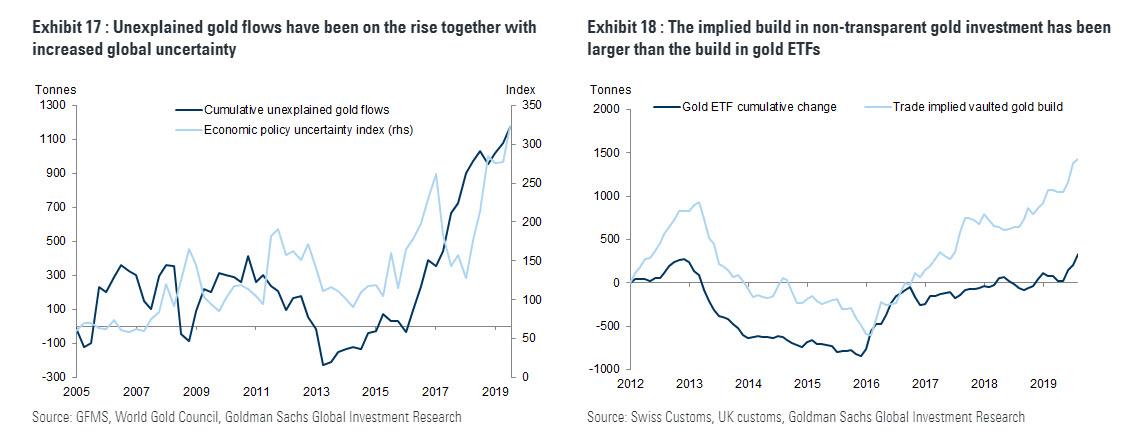

But it was another, even more bizarre discovery by Goldman, that caught our eye: according to the bank there has been a whopping 1,200 tons, or $57 billion, of “unexplained” gold flows in just the 3 years.

As Goldman’s Mikhail Sprogis writes, “rising political risk – together with negative European rates – may be an important reason behind the large share of unaccounted gold investment over the past several years. Exhibit 17 shows cumulative unexplained gold demand based on World Gold Council (post 2010) and GFMS (pre 2010) balances data. It surged since 2016. Similar dynamics can be seen when we look at implied vaulted gold stocks built in the UK and Switzerland, which is calculated as implied cumulative total net imports minus transparent ETF gold stocks.”

And another remarkable observation, or rather lack thereof: “One can see that since the end of 2016 the implied build in non-transparent gold investment has been much larger than the build in visible gold ETFs (see Exhibit 18). This is consistent with reports that vault demand globally is surging. Political risks, in our view, help explain this because if an individual is trying to minimize the risks of sanctions or wealth taxes, then buying physical gold bars and storing them in a vault, where it is more difficult for governments to reach them, makes sense. Finally, this build can also reflect hedges by global high net worth individuals against tail economic and political risk scenarios in which they do not want to have any financial entity intermediating their gold positions due to the counterparty credit risk involved.”

In other words, Goldman points out that just over the past three years, there have been tens of billions in gold flows which have mysteriously and inexplicably disappeared from the official record, yet which are most certainly taking place behind the scenes as the world’s “top 1%” brace for a major shock.

But it’s not just gold that is disappearing: according to the WSJ, so is the world’s cold, hard cash.

Some Australians are burying it. The Swiss might be hiding it. The Germans are probably hoarding.

Indeed, while banks are printing more bank notes than ever and, these seem to be “disappearing off the face of the earth” and nobody knows where or why. or as the WSJ notes, “central banks don’t know where they have gone, or why, and are playing detective, trying to crack the same mystery.”

We do know one thing: of the $1.7 trillion in US dollars in cash circulation in 2018 (up from $1.2 trillion 5 years prior), the vast majority is offshore, where it is quickly and quietly disappears as the world’s second best physical store of value (after gold of course). A Fed economist, Ruth Judson, wrote in 2017 that about 60% of all U.S. currency, and about 75% of $100 bills, had left the country by the end of 2016 — for a total of about $900 billion in U.S. dollars kept overseas. Socking those bills away “provides some protection against economic turmoil, especially in countries with a record of instability in their own financial systems”, the paper said.

Take Australia: there the stock of Australian bank notes on issue relative to the size of the economy is near the highest it has been in 50 years, said Philip Lowe, governor of Australia’s central bank: “He showed off newly printed bank notes to diners at a recent event in Melbourne and estimated that about $2,000 in printed bills exists for every Australian.” And just to inspire confidence in his own job, he added: “I, for one, don’t have anywhere near that amount” on hand. In a few years, he will wish he did.

To be sure, there is the criminal element: as anyone who has watched a documentary on Pablo Escobar knows the Colombian drug kingpin buried tens of billions in the ground for “safe keeping” (in fact, as “The Accountant’s Story” writes, “Pablo was earning so much that each year we would write off 10% of the money, or about $2.1 billion, because the rats would eat it in storage or it would be damaged by water or lost“). As such, dollar bills are often vital grease for criminal gangs and tax cheats.

Physical cash is also popular with preppers and “collectors” who worry about a future collapse of the financial system.

But these two groups are far too small to explain the wholesale loss of cash as central bankers scramble to “follow the money” and glean how society’s saving and spending patterns change in a time of zero and negative interest rates. As the WSJ notes, bankers aren’t just hunting down cash to satisfy their own curiosity. If central banks don’t know how much cash is out there, they could print too much currency and risk inflation.

Then there are bizarre incidents such as these:

Construction workers recently dug up an estimated $140,000 buried in packages at a site on Australia’s Gold Coast, prompting a police search to find the trove’s owner.

In September, a court in Germany ruled on a case brought by a man who stuffed more than 500,000 euros in a faulty boiler only to see it incinerated when a friend made a fix on a cold day while he was on vacation. The man sued his friend for the value of the lost bank notes plus interest. He lost.

“People hide their money everywhere,” said Sven Bertelmann, head of the Bundesbank’s National Analysis Centre in Mainz, Germany. Sometimes bank notes are buried in the garden, where they start decomposing, or hidden in attics, where they are used by mice for building nests. “It happens again and again that people keep money in an envelope and then they shred it by mistake,” Mr. Bertelmann said. “We pick up the bank notes with tweezers and then start to put them together, like a jigsaw puzzle.”

Few are as perplexed by the fate of the missing cash as the German central bank: according to the Bundesbank more than 150 billion euros are being hoarded in Germany.

This has led the European Central Bank, and others, to ask the public for help.

“Everyone says that they are not hoarding cash but the money is clearly somewhere,” said Henk Esselink, head of the issue and circulation section in the ECB’s currency management division.

Some stunning facts: Australia’s central bank says its best guess is that only around a quarter of the bank notes in circulation are used for everyday transactions. Up to 8% of cash is used in the shadow economy—tax avoidance or illegal payments—while as much as 10% could have been lost. That is $7.6 billion Australian dollars ($5.2 billion) missing at the beach or in couch cushions… Or simply lost in a “boating accident” to avoid the taxman until the rainy days arrive.

The biggest use of cash is as a store of wealth “in safes, under beds and at the back of cupboards, both here in Australia and elsewhere around the world,” Mr. Lowe, the RBA governor, said.

Officials at the Swiss National Bank came up with another theory: hoarded bank notes should wear out less because they aren’t being used for everyday transactions. Demand for high-denomination bank notes tends to rise when interest rates are low, households feel distrustful of the banking system or people want to make transactions anonymously.

Sure enough, SNB officials found that hoarding of Swiss francs jumped around the year 2000, likely motivated by fear of the Y2K bug infecting computer systems, the bursting of the dot-com bubble, the September 11 terrorist attacks and introduction of the euro. The financial crisis that began in 2007 encouraged people to stash even more.

Meanwhile, with a financial crisis looming – and getting closer by the day – for some countries, such as New Zealand, making money disappear is becoming a national pastime.

As the WSJ concludes, around a third of New Zealand’s new bank notes headed overseas in 2017, up from 6% four years earlier. That happened around the time that tourism overtook dairy as the country’s main export money-spinner, leading officials to speculate on the role played by currency exchanges, especially in Asia.

The trail mostly ran cold after that. The bank could only identify the whereabouts of around 25% of New Zealand’s cash. The rest, of about 75%, has disappeared.

“Our sense is that we’re in the same boat as a lot of other central banks out there,” said Christian Hawkesby, assistant governor at the RBNZ. “We can’t fully explain why holdings of cash are rising and where they are going.”

Well, Christian, the answer to where all that cash is going is simple and is shown on the image below…

Tyler Durden

Sat, 12/14/2019 – 19:00

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/34ntc9t Tyler Durden