Merchants Of Thirst

Authored by Kip Hansen via WattsUpWithThat.,com,

This story represents the ubiquity of blaming climate change as a means of avoiding responsibility for the failings of civil society. It is interesting that even wealthy countries like South Africa suffer the same problems – albeit on a lesser scale – as seen in poor and developing countries. Money cannot obviate the damage caused by lack of governmental foresight and lack of continuing infrastructure investment. I grew up in Southern California, living through periods of drought and periods of seemingly endless rains that washed homes and whole mountainsides into the sea. For those with interest, the movie-classic “Chinatown” tells some of the story.

* * *

Water tankers ply the city streets bringing essential supplies of fresh potable water to thirsty neighborhoods.

“For city authorities that are already struggling to maintain the current supply as climate change strikes, let alone source additional water, tankers can seem like a safety net they feel powerless to resist.’’

So Peter Schwartzstein writes in a feature piece in the New York Times titled “The Merchants of Thirst” in the 11 January 2020 online edition.

The Times’ article is about a real and important issue: the inability of many cities in developing countries — and sometimes well developed countries, such as South Africa — to provide adequate clean, safe and drinkable fresh water to homes and businesses, even in their larger cities.

To fill the gap, fleets of water tankers (as pictured in the featured image) roam the streets of these cities, delivering much needed water to homes and businesses, filling everything from large 100 gallon tanks to 5-gallon jerry cans and even 1-gallon jugs. Of course, in most cases, the tankers are selling this water to desperate customers.

I can confirm from personal experience in Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands and the Dominican Republic that this is a real and ongoing problem. It is more often the poor that end up paying the sometimes exorbitant prices demanded by the tankers — they have no choice when water ceases to come out of the pipes. Note that the wealthier neighborhoods are less commonly under-served by the municipal water supply — and when they are cut off — they have standby water tanks pre-filled and fitted with electric water pumps to ensure that water continues to flow when the faucet is turned on. High-rise apartment complexes sell themselves on their ability to supply 24/7 electric power utilizing on-site dedicated diesel generators and 24/7 water supply — from on-site multi-thousand gallon cisterns buried beneath the building.

Every country I have visited, with the exception of those in Europe, uses water tankers for some purposes. Even where I live in Upstate New York, there are water tankers that fill swimming pools in the spring and dump water down dry wells in the late summer.

Many of us may not realize that when there is no water flowing out of the pipes it means: No showers, no baths, limited cooking, no dish washing, no clothes washing, no toilet flushing.

[In the Dominican Republic, it was common practice for homes to have a 50-gallon drum in the bathroom — which would be kept full with a hose from the sink or shower — next to the toilet. A gallon-sized water scoop made from a used bleach bottle could then be used to flush the toilet even when the water pipes ran dry.]

Apparently in keeping with the NY Times’ editorial narrative for climate change — which seems to require that every story on an ever-longer list of topics blame climate change for any and all negative circumstances — the problems related to Water Tankers in various places is hinted to have something to do with Climate Change, which is claimed to be adversely affecting the water supply in these places. However, it is in fact almost totally unrelated, even where there are real, physical problems such as drought.

In one word: Infrastructure

The real-world problem is infrastructure — inadequate, often antiquated, infrastructure. That is both not enough infrastructure and failing infrastructure.

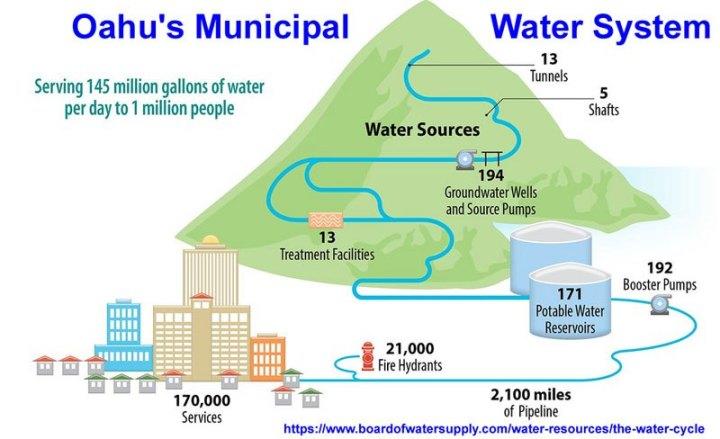

To deliver fresh potable water to homes and businesses, these cities must have a whole list of major items; as illustrated in this diagram of Oahu, Hawaii’s water system:

1. Sources of water — dependable rivers, reservoirs, aqueducts and water treatment facilities to sanitize the public water supply.

2. A water distribution system — once the water is treated, it must be distributed throughout the city — down every street to every home, apartment building and business. This distribution system has valves and booster pumps and supply mains and distribution pipes of adequate size to meet the demand of customers.

3. In many cases in poorer countries, public water fountains and faucets need to be supplied for those neighborhoods not served with water piped directly into individual homes.

Schwarzstein reports;

“But no matter how hard the [tanker truck] crews worked or how furiously they pushed their lumbering vehicles over the potholed roads, there was no satisfying the city’s needs. The going was too slow. The water shortage too severe.’

The fake news is right there. It is the sentence “The water shortage too severe.”

What water shortage?

There was no water shortage — not in Kathmandu. There was a water delivery problem — a water infrastructure problem — Schwartzstein reports it — right after the false information. The whole article starts with the truth “It had been 11 days since a ruptured valve reduced Kupondole district’s pipeline flow to a dribble,…” — a valve in the water supply main had ruptured leaving the neighborhood without water. He goes on later: “By the time the pipeline was fully restored, some households had subsisted on nothing but small jerrycans for almost an entire month.”

There is nothing in the entire article about an actual water shortage in Kathmandu — yet the Times’ author repeats three times that the problem is water shortages and climate change. He cites problems in Chennai, Indian and in Cape Town, South Africa.

They have had problems in Chennai, India, which has traditionally depended on the Indian monsoons to supply water but where the reservoirs have been allowed to silt up reducing their capacity while the population of the city of Chennai has grown out of control — without any additional investment in water infrastructure — no new reservoirs.

Time Magazine reported the Cape Town situation as:

“The Cape Town crisis stems from a combination of poor planning, three years of drought and spectacularly bad crisis management. The city’s outdated water infrastructure has long struggled to keep up with the burgeoning population. As dam levels began to decline amid the first two years of drought, the default response by city leadership was a series of vague exhortations to be “water aware.”

Not enough water or too many people?

Both, actually. Chennai, India had a population of 4 million in the year 2000. Today there are almost 11 million. [World Population Review reports 10,971,108] — nearly a three-fold increase in twenty years. In 2001, Kathmandu had a population of 671,846, today it is just under 1.5 million — more than doubled. Cape Town population in 2001; 2,900,000; in 2020 4,617,560 — adding one and a half million additional people, plus businesses and agriculture.

Rich or poor, localities cannot expect to meet the water needs of today with the infrastructure of the past century.

We see these recurring factors: There are too many people in an area without dependably sufficient natural fresh water supplies — in Chennai and Cape Town — both in naturally dry areas which are prone to drought. We see burgeoning populations without commensurate increases in water supply infrastructure and, in many cases, without adequate maintenance of existing, already inadequate, infrastructure — particularly in Kathmandu. The island of Phuket, Thailand, dependent on monsoonal rains, had water problems last year — with the same factors — skyrocketing population and inadequate water supply infrastructure. In each case, we see poor government — poor planning — poor crisis management.

And we see weather — good weather, bad weather, too dry weather, too wet weather. And we see slowly changing, ever changing climatic patterns with broad changes in atmospheric and oceanic circulations — and the coming and going of El Niños and La Niñas.

To deal with ever changing weather, and slowly changing climate, requires good government and adequate national wealth, well spent, to prepare first for the present, and then for the inevitable but unpredictable possible futures. All three of the localities covered in the Times have not even properly planned for the present — not kept water supply infrastructure up to the task of keeping up with population growth and local water needs of agriculture and business — not even in fully modern Cape Town. India, Nepal and Thailand are in far worse situations — broken and inadequate infrastructure, planning decades behind the needs of times, governments without sufficient funds to make needed corrections and additions.

Politicians fall back on blaming Climate Change — something they can’t be expected to be held responsible for — for their own shortcomings and failures. The international community is equally happy to blame Climate Change for the misery of local peoples left without basic cheap clean safe water supplies — blaming climate, the universal scapegoat, rather than supplying humanitarian aid to help where it is really needed.

The international community needs to focus more of its humanitarian aid effort on the real and pressing problems of water supply in developing nations — a pragmatic approach that will be a win-win regardless of the vagaries of climate.

Without any need to invoke Climate Change, Cape Town’s narrow escape should inform the megalopolises of the American Southwest (in particular Southern California but including such cities as Phoenix, Arizona and Las Vegas, Nevada) of their imminent and possibly unavoidable danger — they share a common Mediterranean climate and are historically subject to droughts and mega-droughts. Both have out-of-control population growth and tourism growth as well as heavy demands of agriculture on water supplies. The American Southwest and especially Southern California are just one extended drought away from a massive water crisis.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 01/16/2020 – 19:10

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2tgMoJD Tyler Durden