Neel Kashkari Appeals To “QE Conspiracists”: Show Me How The Fed Is Moving Stock Prices… So Here It Is

Things are starting to get surprisingly heated at the Fed, now that not only Wall Street strategists, and traders but also Fed presidents are starting to tell the truth about how the Fed’s “NOT QE”, which sorry but we will call it by its real name QE 4, is pushing stocks to ridiculous nosebleed record levels (as one can see by the relentless meltup in the S&P over the past four months), at valuations that are now higher the dot com days.

It all started when, in a moment of bizarre honesty, Dallas Fed president and former Goldmanite Robert Kaplan admitted in a Bloomberg interview that the expansion of its balance sheet was helping to lift asset prices. Commenting on the Fed’s massive liquidity response to the JPMorgan-precipitated repo-market crisis (it’s not just our view that Jamie Dimon caused the repo crisis), which triggered not only the first Fed use of repos since the financial crisis, but also $60 billion in monthly T-Bill QE, Kaplan said that “my own view is it’s having some effect on risk assets”, adding that “It’s a derivative of QE when we buy bills and we inject more liquidity; it affects risk assets. This is why I say growth in the balance sheet is not free. There is a cost to it.“

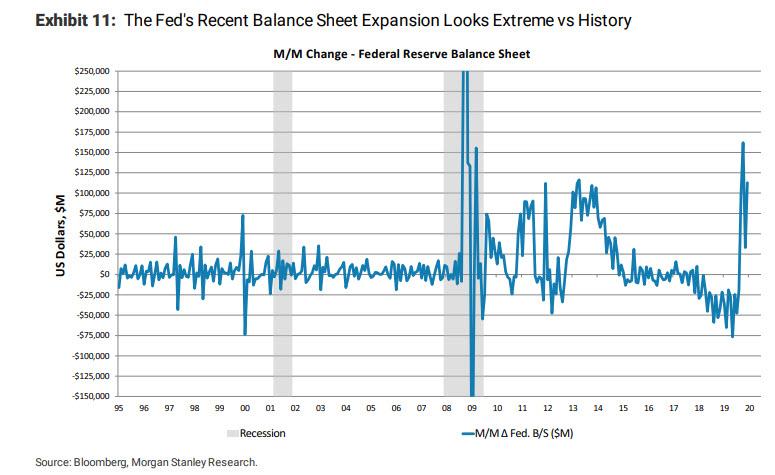

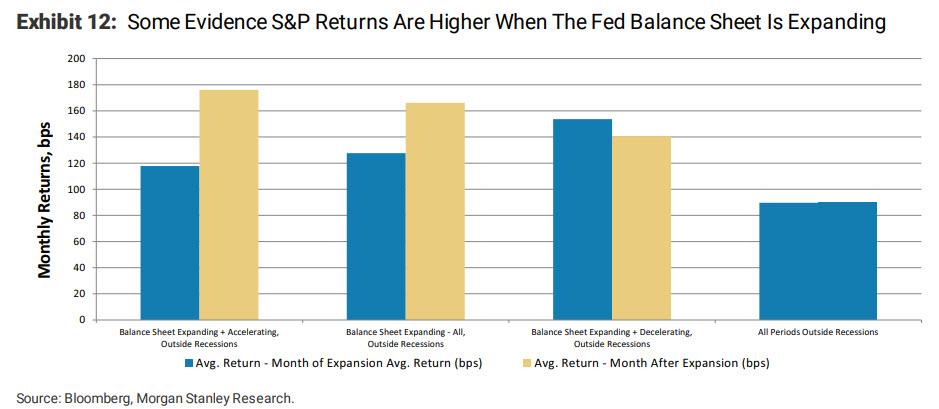

This interview followed just days after one of Wall Street’s most closely followed strategists, Morgan Stanley’s Michael Wilson wrote a report in which he said that “as the Fed has expanded the size of its balance sheet, we have been of the view that the resultant excess liquidity has been beneficial for stock prices and multiples. The potential impact of the Fed on equities has been a central feature of almost all our client conversations the last few months. Most clients suspect that there is some positive impact, though the transmission mechanism and quantification of that impact are hard to pin down, limiting confidence in its durability now that asset prices appear ahead of the fundamentals (Exhibit 1). Since the Fed has rarely expanded its balance sheet at the pace it has been on since October there is limited history to analyze, but we found some evidence that periods of balance sheet expansion have lined up with above average equity returns.”

Wilson then noted that “an expanding balance sheet outside of recessions has coincided with above-average monthly returns for the S&P”, something we have been pointing out since October.

Kaplan’s long-overdue admission, which confirmed everything we have said since 2009, prompted an avalanche of cathartic hot-takes from traders who, until now, had kept silent out of fear of being ostracized by their colleagues for espousing such a “tinfoil” conspiracy theory, first and foremost Bloomberg’s Richard Breslow who yesterday published a furious screed slamming the Fed for, well, everything we have been accused it of doing since 2009. Here, again, are the highlights:

Well the cat’s out of the bag. The worst kept secret in the financial world is now not only accepted orthodoxy, but finally being discussed openly by, at least some, authorities. Central bank policies are directly driving asset prices and the bubbles therein. It’s what they do. It has been so stunningly obvious that, at this point, it makes a mockery of things to deny it as an ongoing, and essential, part of how their strategy is implemented. Oddly enough, however, it’s a revelation that is, apparently, coming late to many people with a lot of savings and nothing to show for it. And it is an undeniable factor in this January’s price action.

Alan Greenspan knew it to be the case. Ben Bernanke had no problem with it. His strategy required it. Jerome Powell, was probably initially not enamored about it but saw no way around it. It fell on ardent loyalists to take his insistence that it was “not QE” with any seriousness. Otherwise, they would have had to admit to knowing little about financial markets

In some ways it was refreshing that Dallas Fed President Robert Kaplan openly talked about it in an interview Wednesday. Although he did couch it in terms that implied it was a matter of some concern to him. But, of course, he went on to say, “we’ve done what what we need to do up until now.” He doth protest, just not so much. Their ability to drive investor behavior is so well established that what is going on in the markets can’t remotely be seen as an unintended, or even unwanted, consequence

At this point, is it a bad thing to admit something that is so patently evident to everyone? The answer is probably yes. They have always been responsive to financial conditions. In many ways they’ve been transfixed by them. Now they are openly acknowledging that they own them. And once you do so, it becomes harder than ever, if even at all possible, to give them back. Kaplan said they need to “come up with a plan and communicate a plan for winding this (balance sheet) down.” That would be nice. And good luck with that.

Then in an amusing twist, almost two months after we first wrote “QE Or Not QE? Here Is The Market’s Answer In One Simple Chart“, Bloomberg, which four months ago hilariously declared “When the Fed Fixes Repo Markets, Don’t Call It QE“, is out this morning with “The Debate Over Whether to Call It QE Is Over, and the Fed Lost“, in which it too concedes that what the Fed is doing is in fact, QE for market purposes… which are all the purposes that matter:

Never mind that Chairman Jerome Powell tells everyone his efforts to shore up funding markets are “in no sense” QE. Try as policy makers may, they’ve lost the ability to convince people that Treasury purchases aren’t at least partially why the Dow Jones Industrial Average is up almost 4,000 points since late August.

Sure, it’s all labels. If you want to call it QE, you can. Or not. If you want to ascribe the rally to Powell, that’s up to you. Certainly the Fed thinks it’s on solid ground. Rather than trying to drive down long-term interest rates to stimulate the economy, a la QE, it’s simply buying T-bills to keep the financial system’s plumbing in order.

“Whether the Fed’s liquidity injection impacted directly the economy or the pricing of assets or not, it’s certainly true that a lot of people think it did,” said Jim Paulsen, Leuthold Group Inc.’s chief investment strategist. “Whether anything is going to change if the Fed takes it away doesn’t matter. If enough people feel it will, then it’s going to impact markets.”

It’s a tad ironic that for all his attempts to convince the market that QE4 is “not QE”, Powell who in October said that “Growth of our balance sheet for reserve management purposes should in no way be confused with the large-scale asset purchase programs that we deployed after the financial crisis”, has less influence on the market’s interpretation of his own actions than, say, fringe, conspiracy blogs.

But we digress.

Fast forward to this morning, when in the latest attempt to preserve the last ounce of Fed credibility with strategists, traders, news services and even its own members are calling the Fed out on its stock market pumping, Minneapolis Fed president, and another former Goldmanite, Neel Kashkari issued a derogatory appeal to “QE conspiracists”, which now includes his Fed peers (and Goldman alumni) such as Robert Kaplan, in which he says that:

“QE conspiracists can say this is all about balance sheet growth. Someone explain how swapping one short term risk free instrument (reserves) for another short term risk free instrument (t-bills) leads to equity repricing. I don’t see it. /end “

QE conspiracists can say this is all about balance sheet growth. Someone explain how swapping one short term risk free instrument (reserves) for another short term risk free instrument (t-bills) leads to equity repricing. I don’t see it. /end

— Neel Kashkari (@neelkashkari) January 17, 2020

Something tells us that when Goldman was giving the lesson on how the Fed creates endogenous liquidity, Kaplan was present and Kashkari was out drafting his TARP bailout vision on a napkin, for the simple reason that the uberdovish Fed president who continues to push for lower rates, appears unable to grasp that both T-Bill monetizations and repo injections create incremental liquidity for financial institutions, something which the 10% rate that overnight G/C repo hit on Sept 16 2019 showed, had suddenly evaporated and prompted the Fed to scramble and inject hundreds of billions in liquidity in the next 4 months.

It was this massive liquidity injection, and not the “asset swap” aspect of QE that has lead the market – and Robert Kaplan – to correctly conclude that the Fed “affects risk assets.“

That said, we can commiserate with Kashkari for not being able to grasp how the Fed’s excess liquidity, which is supposed to assist dealer banks which ended up with insufficient liquidity during the repo crisis, is transformed into a higher risk asset prices. After all, Fed presidents certainly are not expected to understand the nuanced monetary plumbing dynamics of the markets they oversee (what’s that, they are, oh nevermind then…).

Conveniently, Mr Kashkari can find the answer he is seeking if he only does a simple google search. After all, we explained it all back in September in “Bank of America Now Calls What Is Coming ‘QE4‘”, then in November in “One Bank Finally Admits The Fed’s “NOT QE” Is Indeed QE… And Could Lead To Financial Collapse“

then again in “A Major Bank Admits QE4 Has Started, And That Stocks Are Rising Because Of The Fed’s Soaring Balance Sheet“

and most notably in “”The Fed Was Suddenly Facing Multiple LTCMs”: BIS Offers A Stunning Explanation Of What Really Happened On Repocalypse Day.”

And in case Neel would rather get his information from other third party sources, we point him to a December BIS report titled “September stress in dollar repo markets: passing or structural?”, which explains clearly and concisely what the transmission channel is for excess Fed liquidity to result in higher asset prices. To save both Neel and readers the pain of reading the full report (although we certainly feel that Mr Kashkari should finally understand how the plumbing of the US financial system works, especially since this year he is a voting FOMC member and his dovish votes will only make the world’s asset bubble even bigger), we present the following except from the media briefing that was associated with the BIS report, in which Claudio Borio, head of the monetary and economic department at the BIS, laid out everything one needs to know:

high demand for secured (repo) funding from non-bank financial institutions, such as hedge funds heavily engaged in leveraging up relative value trades

This explains the demand side behind the September repo crisis, one which the Fed, Kashkari and virtually everyone else ignores, and instead focuses on the supply, or lack thereof, of liquidity, i.e.:

… the big four banks’ unwillingness to supply the funding, as their liquidity buffers, notably in the form of excess reserves with the Fed, were running low.

And while the Fed did everything in its power to boost the supply side by first opening up the repo taps and then launching QE4, it remained ignorant about the demand side, namely the hedge funds that were using repos to massively lever up on tiny arb pair trades which as we explained in December, consisted of buying US Treasuries while selling equivalent derivatives contracts, such as interest rate futures, and pocketing the arb, or difference in price between the two.

Does this remind readers of a trade popularized by another hedge funds in the 1990s? If you said LTCM give yourself a pat on the back. And it was the fear that the repo crisis would transform into an LTCM-like contagion that sparked the Fed’s massive liquidity injection, and also the resultant surge in risk prices once concerns about the viability of hedge funds dissipated.

And here, once again for the benefit of Kashkari, this is how the BIS explains how the financial system came close to the verge of collapse on September 16, poetically enough the 11 year anniversary of Lehman’s bankruptcy:

Shifts in repo borrowing and lending by non-bank participants may have also played a role in the repo rate spike. Market commentary suggests that, in preceding quarters, leveraged players (eg hedge funds) were increasing their demand for Treasury repos to fund arbitrage trades between cash bonds and derivatives. Since 2017, MMFs have been lending to a broader range of repo counterparties, including hedge funds, potentially obtaining higher returns. These transactions are cleared by the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC), with a dealer sponsor (usually a bank or broker-dealer) taking on the credit risk. The resulting remarkable rise in FICC-cleared repos indirectly connected these players. During September, however, quantities dropped and rates rose, suggesting a reluctance, also on the part of MMFs, to lend into these markets (Graph A.2, right-hand panel). Market intelligence suggests MMFs were concerned by potential large redemptions given strong prior inflows. Counterparty exposure limits may have contributed to the drop in quantities, as these repos now account for almost 20% of the total provided by MMFs.

So where does that leave us? Well, as the BIS concludes, since 17 September, “the Federal Reserve has taken various measures to supply more reserves and alleviate repo market pressures. These operations were expanded in scope to term repos (of two to six weeks) and increased in size and time horizon (at least through January 2020). The Federal Reserve further announced on 11 October the purchase of Treasury bills at an initial pace of $60 billion per month to offset the increase in non-reserve liabilities (eg the TGA). These ongoing operations have calmed markets.”

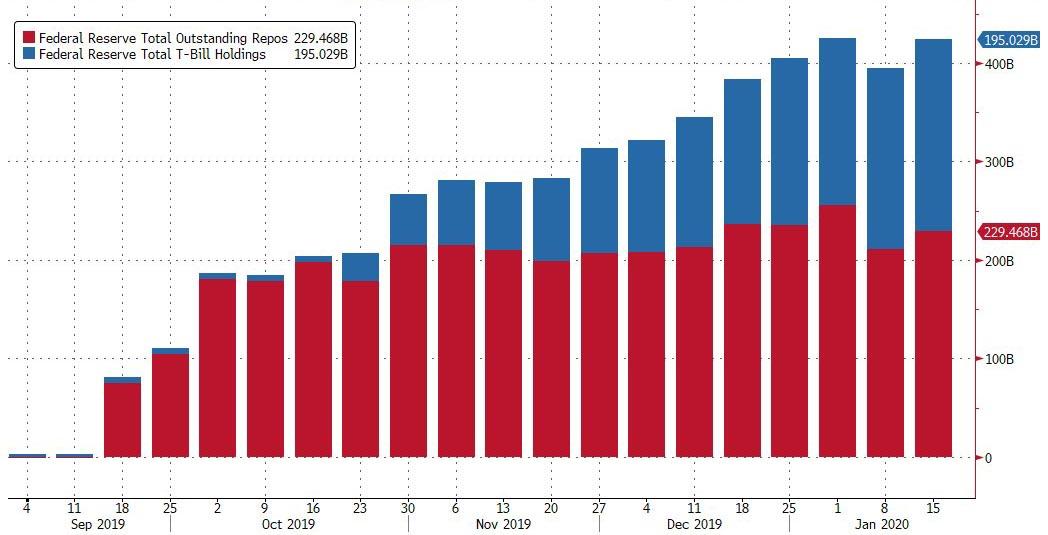

We have covered all these mitigating events, and the problem is that even though the Fed has now injected $230BN in liquidity via overnight and term repos, and $195BN via permanent T-Bill purchases, or POMO (i.e. “QE 4”), expanding the Fed’s balance sheet by $322 billion, the repo market still remains broken.

Worse, in order to keep banks well supplied with liquidity and hedge funds content and preventing them from closing out of these massively levered pair trades, last week repo expert Scott Skyrm said that the problem with the broken repo market and the Fed’s respective Repo operations, similar to the problem observed with QE and the Fed’s balance sheet in general over the past decade, is that the market is now addicted to the easy Fed liquidity.

As Skyrm wrote, “it’s easy to see how the Repo market can get addicted to easy cash from the Fed when the stop-out rates for the RP operations are 1.55% – behind the offered side of the market.” But, as the repo strategist adds, as the Fed keeps injecting cash, the market gets used to it.

Which is great in the short-term as it sends risk assets soaring as hedge funds put on even more risk-chasing trades via repo, but becomes a major issue over the long-term: “The long-term problem is that the some investor cash (real money cash) that was once going into the Repo market is now going elsewhere”, Skyrm explains. Indeed, the problem is that repo rates are trading in the lower end of the fed funds target range. When GC rates were higher in the range, Repo general collateral, as an investment, was more competitive than other overnight rates. But now that cash has gone to other markets, meaning the Fed is trapped in providing liquidity in perpetuity unless it hikes rates which in turn will cause a market crash.

In short, just as the market got addicted to QE and the result was a 20% drop in the S&P in late 2018 when markets freaked out about Quantitative Tightening, the Fed’s shrinking balance sheet, and declining liquidity, Skyrm cautions that “it will take pain to wean the Repo market off of cheap Fed cash” since “it‘s a circle” which can be described as follows:

For the Fed to end daily RP ops, they need outside cash to come back into the Repo market. For the Repo market to attract cash, Repo rates need to move higher. For rates to move higher, the Fed needs to stop RP ops.

The problem is that stopping RP ops could spark another repo market crisis, especially with $230BN in liquidity still being pumped currently via Repo. It also means that the Fed is now unilaterally blowing a market bubble with its repo and “NOT QE” injections, and yet the longer it does so the more impossible it becomes for the Fed to extricate itself from the liquidity pathway without causing a crash.

Or stated simply, the longer the Fed avoids pulling the repo liquidity band-aid, the bigger the market fall when (if) it finally does. The question then becomes whether Powell can keep pushing on the repo string until the November election, because a market crash in the months preceding it, especially since it will be of the Fed’s own doing, will result in a very angry president.

Krishna Memani, former vice chairman of investments at Invesco, agrees: “Powell went out of his way to explain that it wasn’t QE, but it doesn’t really matter. The Fed is in a bind. Effectively with policy initiatives they have, they have to increase reserves, and investors are aware of that. They will be in that mode for the foreseeable future.”

* * *

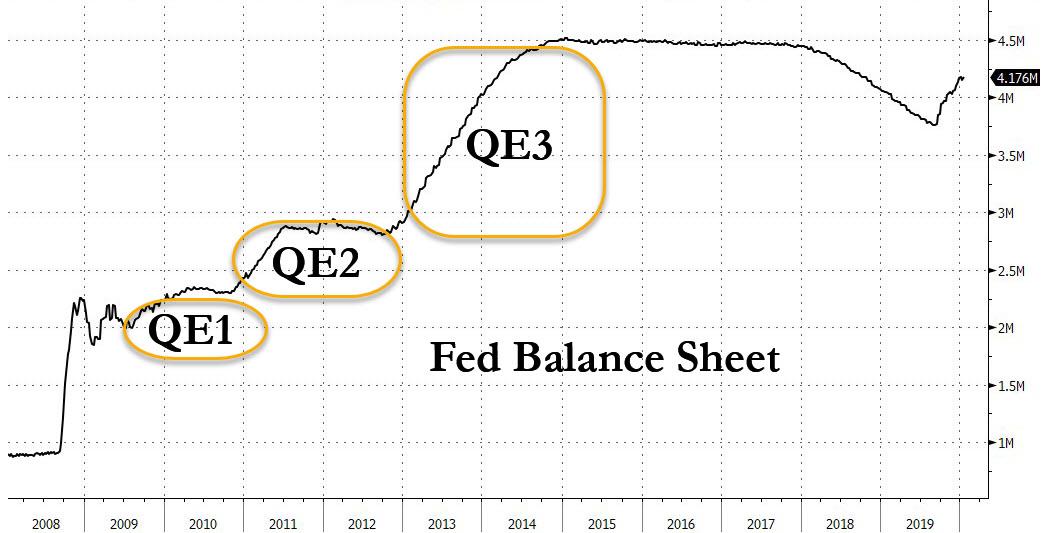

All that, dear Neel Kashkari, is how the record pace of expansion of your balance sheet, which is growing at a faster rate than during QE1, QE2 or QE3 …

… is sending stocks to new all time highs every single day.

Tyler Durden

Fri, 01/17/2020 – 11:08

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/371ymtW Tyler Durden