“The 2-Child Policy Has Failed”: China’s Birth Rate Hits Record Low As Growth Slows

China finally abandoned its controversial one-child policy in November 2013. But more than six years later, millions of Chinese couples are still unwilling to have a second child. And that’s a huge problem for the Communist Party, whose legitimacy in the eyes of the public depends on its ability to deliver on promises of unbridled growth and prosperity.

And who can blame them? Entrenched behaviors die hard, and after the government’s brutal treatment of citizens who defied its policy (which was initially imposed to ward off famine), we can sympathize with Chinese who simply believe that having two children isn’t in keeping with the fundamentals of patriotic socialism with Chinese characteristics.

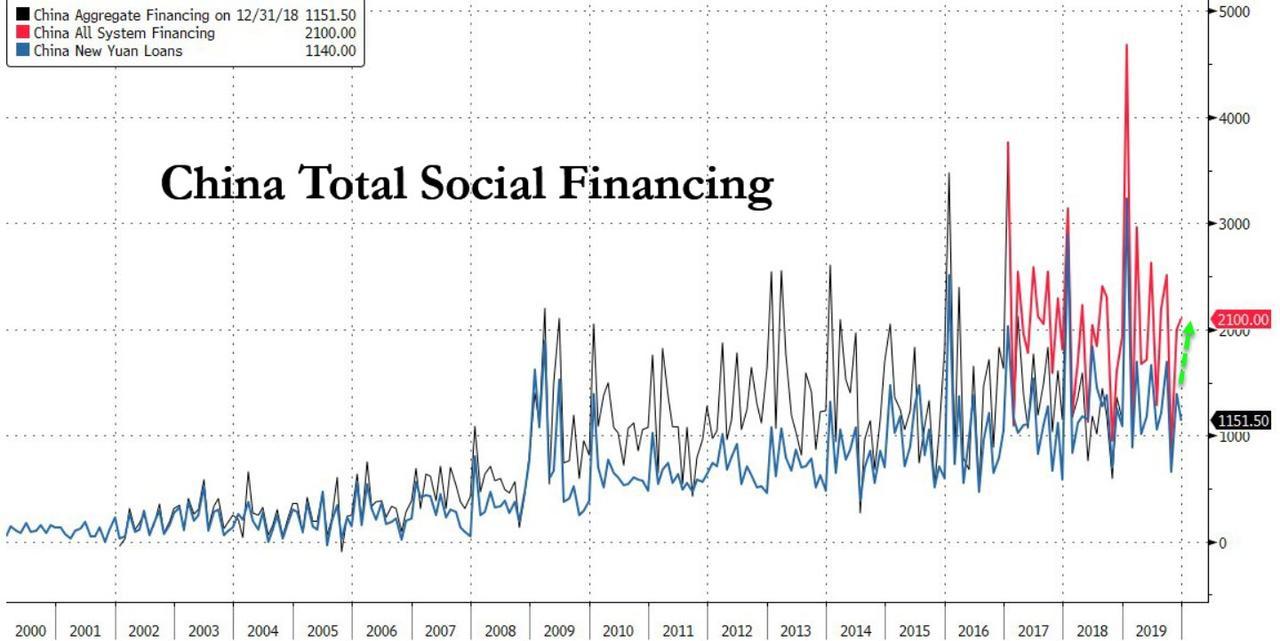

But as the FT reported this week, issues of culture and perception aren’t the only reasons Chinese women are still refusing to have more than one child. As we reported last week, Chinese GDP growth slowed in 2019 to its weakest level in 29 years…

…proving unequivocally that Beijing’s massive credit stimulus hasn’t done much, if any, good.

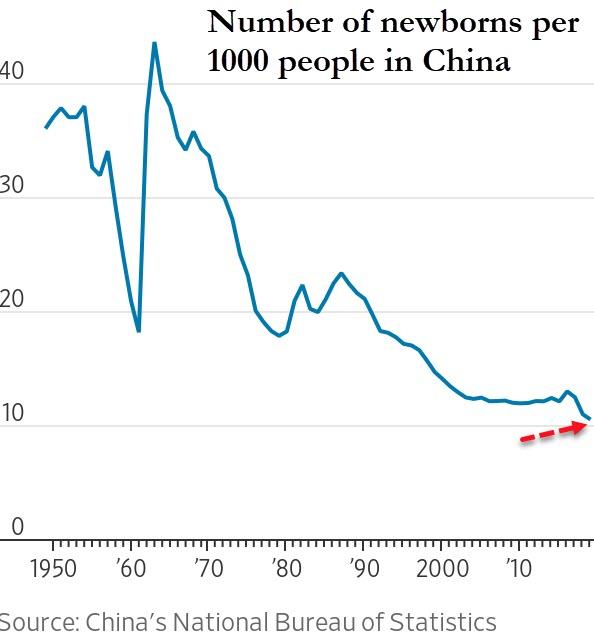

Meanwhile, official statistics agencies reported that China’s birth rate dropped to 1.05%, a record low. That’s equivalent to 10.5 births per thousand Chinese.

The UN expects China’s population, the largest of any country in the world, to start declining by the end of this decade.

It’s the latest sign that the ‘two child policy’ is now considered an abysmal failure – so much so that party functionaries are apparently unafraid of discussing this fact with the Western press.

Weng Wenlei, vice-president of the Shanghai Women’s Federation, a government body, said birth rates in Shanghai had plunged despite efforts to relax China’s population control. She said births in the city had fallen “swiftly” following a brief recovery in 2016, when China began allowing couples to have two children.

“This suggests [the two-child policy] has failed to serve its intended purpose,” said Ms Weng. “Consistently low birth rate will have a negative impact on Shanghai’s social and economic development.”

Leftists in the US love to complain about the costs associated with having a baby, even for couples who have insurance. But even in a society where most of the people’s health-care needs are met by the state, Chinese citizens are still put off by the cost of care.

Josephine Pan, a Shanghai-based data analyst, abandoned plans to have a second child after spending half of her family’s monthly salary of Rmb20,000 ($2,900) on her seven-year-old son. “It costs a fortune to raise a child,” said Ms Pan, 41, who after giving birth gave up her decade-long hobby of buying designer bags. “I couldn’t afford a second one.”

Women in China are still reluctant to have children, even with the state promising cash handouts to couples who have two children, because they fear more children will hurt their careers.

As in the west, a growing number of Chinese women are reluctant to have babies because they fear children would hurt their career. Chinese employers have a tradition of discriminating against pregnant workers as many female staff face demotion, if not unemployment, after returning from maternity leave.

“I don’t want to risk my career to have a second child,” said Lucy Zhang, a Beijing-based newspaper editor with a five-year-old daughter. “I have worked so hard to get to where I am now.”

All signs suggest that public sentiment is firmly entrenched against breeding. Surveys carried out in Shanghai and Shanxi province last year suggested that the number of women willing to have a second child is languishing between 10% and 25%. Furthermore, only 6.7% of women in Shanghai who are of child-bearing age and also possessed a local residence permit, or hukou, gave birth to a second child in 2018.

“Raising a child takes so much time and energy,” said Mary Xu, a Shanghai-based magazine editor who has a three-year-old daughter. “I have had enough.”

Though they are largely ignored or censored in the mainland press, China’s debt burden is already becoming unwieldy. Last month, a state-owned giant defaulted on a dollar bond, the largest default in two decades. But the issues of being over-leveraged aren’t strictly limited to the corporate sector. Local government financing vehicles are also in trouble.

China bulls in the west argue that the Communist Party exercises such an unshakeable hold on the economy that they simply won’t allow for a systemic debt cross-default. But as the party struggles to contain capital outflows, the country’s reliance on monetary stimulus is finally pushing up against the boundaries of what’s possible.

To be sure, China isn’t the only country struggling with population shrinkage: 27 countries have fewer people now than in 2010. The UN expects 55 nations, including China, to experience declines between now and 2050. Most of these are countries have developed economies, a status that China has only recently achieved.

A declining population places inevitable constraints on economic growth. And as China’s momentous rate of growth slows, its economy will come to resemble a frog sitting in a pot of water on a hot stove.

For investors hoping to increase their exposure to China at a time of slowing growth, when the Chinese economy faces myriad difficulties, slowing population growth might create an opportunity in China’s domestic government bond market, according to one of WSJ’s Heard on the Street columnists.

Numerous studies suggest that a shrinking population should cause real rates to fall. And of course we have a real-world example of this phenomenon in Japan, where government bond prices have never been higher. Of course, this doesn’t necessarily guarantee that the Chinese bond market will follow suit. But it’s certainly some worthwhile food for thought.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 01/22/2020 – 23:45

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2NT7DrX Tyler Durden