Morgan Stanley: Rushing To Reopen The Economy Would Backfire

Authored by Andrew Sheet, Morgan Stanley chief global strategist

Short-Term Pain for Long-Term Gain

Late last year, I met with the pension fund for a physicians’ association in the western United States. I’ve been thinking a lot about that meeting recently, especially when some aspect of the market, or working from home, is particularly frustrating. However disrupted things may seem at the moment, they pale in comparison to what those in medicine, services and other fields at the front line of the response to the coronavirus are going through. So, this seems like a good time to emphasize a key part of our view: What’s best for fighting the pandemic, the health of the economy, and the market may be the same thing – making sure the reopening of the economy is done right.

In thinking about the path for the economy, Morgan Stanley’s economists and healthcare analysts have been working together. In last week’s Sunday Start, my colleague Matthew Harrison wrote about how we see virus dynamics beyond the ‘peak’, and how this informs our economists’ expectations for a ‘re-opening’.

As Matthew emphasizes, a sustainable re-opening requires that four key components are in place:

- adequate surge capacity in hospitals,

- public health infrastructure to support testing,

- robust contact tracing to curtail ‘hot spots’ and

- widespread access to serology testing (to determine who is already immune to the virus).

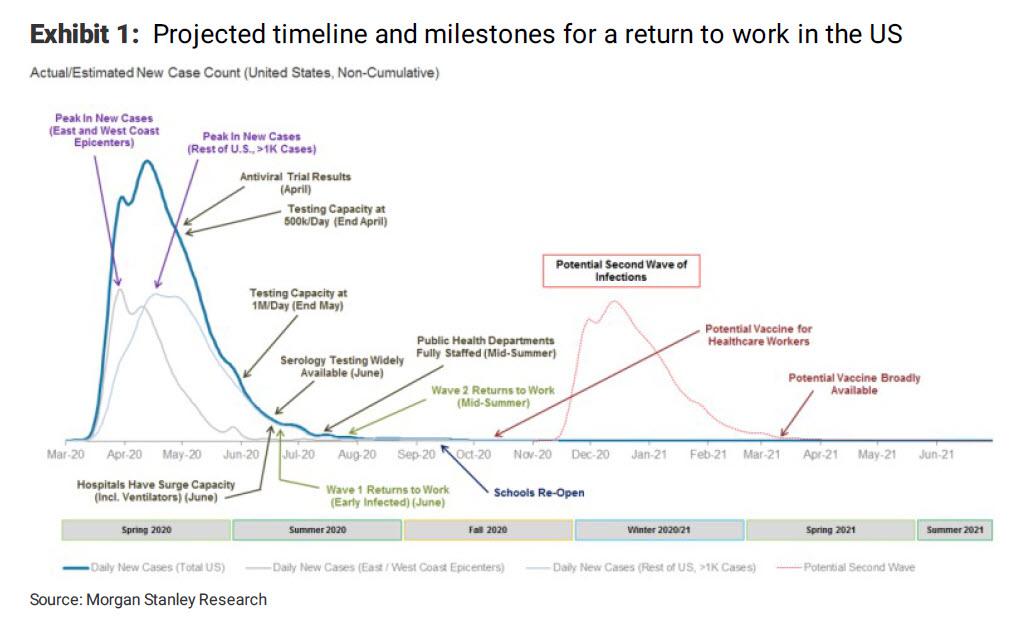

We see the process unfolding in waves, starting in mid-summer. Even then, however, the return to work will be slow, with our economists not expecting to see pre-recession levels of output for US or global growth until 4Q21.

When the discussion turns to markets, however, it is often presented as a trade-off: The faster the re-opening, the less pressure on earnings, defaults and asset prices. We disagree with this framing.

If you give investors confidence that the worst is behind them, history suggests they can put up with quite a bit of bad news. We think this is especially true for credit spreads and levels of volatility, which often hit their worst levels several months before the trough in economic data (and even farther ahead of things returning to ‘normal’). If, as we forecast, April and May represent the low of economic activity in the US, a market low in March would be very consistent with past patterns of market anticipation.

Indeed, the best times to invest are often when a weak economy creates lower prices. We hear investor concerns about a coming rise in default rates and large declines in earnings (we forecast these too). But credit spreads have tended to improve well ahead of the peak in default rates, while equity markets represent the present value of all future cash flows from now until the end of time. The former is a reason why my colleague Srikanth Sankaran is overweight corporate credit, the latter is a reason why my colleague Michael Wilson recently raised his year-end target for the S&P 500 to 3000. And both are reasons why we think equity volatility can fall further from here.

We think this applies even in the face of 2Q20 looking to be the worst quarter for economic activity in any investor’s lifetime. As long as investors are confident that the next quarter is a little better, and the path from there is improving, we think markets will be more forgiving of poor data.

But this thinking is predicated on April and May being the low for US and global activity. Trying to reopen the economy before the four key prerequisites are in place would inject significantly more uncertainty over whether the worst for the economy is behind us by the end of 2Q. Such a scenario would pose a clear risk to our positive bias towards current markets.

In short, we don’t see a trade-off between what’s required to control coronavirus cases and a better long-run impact for markets and the economy. Fascinatingly, over 100 years ago, the same appeared to be true. In an article for Liberty Street Economics, Fight the Pandemic, Save the Economy: Lessons from the 1918 Flu, March 27, 2020, Sergio Correia, Stephan Luck and Emil Verner from the New York Federal Reserve looked at the response of different cities to the 1918 pandemic. The whole article is great and well worth a read, but the conclusion is striking: Cities that implemented stronger social distancing measures ultimately saw higher levels of industrial production. Fighting the pandemic and protecting the economy were one and the same (in 1918, the Dow Jones Industrial Average rose 10%).

One of the cities with the most aggressive measures and strongest ensuing recovery was Seattle, Washington. Witnessing that response was the reason why my grandfather went into medicine, ultimately following the path of so many in the US whose parents had been born elsewhere. Today’s challenges are serious, scary, but also surmountable. What’s best for fighting the pandemic, protecting the economy and supporting the market may actually be one and the same. Draw a line under the worst of the crisis, and investors can sail through the squall.

Tyler Durden

Sun, 04/19/2020 – 18:05

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2VmETvR Tyler Durden