Here Are The Answers To The Two Questions Most Frequently Asked By Bond Investors

With bond yields trapped in an painfully narrow – almost Yield Curve Control-ish – range in the past month, rates investors have been torn between two extremes: does the ongoing economic recession assure disinflation for the next decade, something which 10Y breakevens stuck just above 1% strongly suggests, or is the upcoming deluge of trillions in new bonds about to send yields exponentially higher as helicopter money and currency debasement prompts nagging questions about the future of the US Dollar as the world’s reserve currency. Meanwhile, a similar dynamic has emerged in the corporate bond market, with the added complexity that the Fed is now also openly buying not just govvies but also corps providing a buyer of last resort, even as the flood of new issuance is unlike any seen in history.

This confusing backdrop serves as the framework for the top 2 questions asked by BMO Capital Markets fixed income clients, which the bank’s rates strategist Ian Lyngen summarizes as follows:

- Will the ultimate impact of the pandemic be inflationary or deflationary?

- How will heavy credit issuance impact spreads?

The BMO rates team offers a brief hot take on both of these questions, starting with the first…

- While there is certainly room for near term downward pressure on inflation, this by no means suggests a deflationary spiral is in the offing.

- The economic recovery will intuitively translate to higher long-end yields as inflation expectations begin to return to the Treasury market. With 5- and 10-year breakevens still extremely low by historical standards at 75 bp and 128 bp, there is more room to the upside barring a complete decoupling of inflation expectations from the Fed’s 2% target

… and the second…

- Supply in the IG corporate market has set successive records, with issuance over $600 bn since March. The USD SSA market is likely to grow by $125-$140 bn over the next three years, led by the largest current borrowers, with the majority of growth coming in 2021 and 2022.

- While corporate leverage is increasing, Fed QE and fundamental credit risk will continue to drive markets in the coming months. Therefore, the increase in issuance is unlikely to materially impact spreads in the near-term.

… before offering a “deep dive” answer to both. So without further ado, here are the answer so the two most frequently asked questions

1. Will the ultimate impact of the pandemic be inflationary or deflationary?

As the domestic economy begins to emerge from lockdown, there is certainly room for near term downward pressure on inflation, though this by no means suggests a deflationary spiral is in the offing. The unprecedented amount of stimulus offered by both Congress and the Fed will continue to flow through to the economy, and by design offset the downshift in consumption which has resulted from shelter-in-place orders and the hit to the labor market. That said, over the near term, it is difficult to envision that the uncertainty caused by the pandemic will translate into a strong propensity to consume, driving a transitory period of low, or even negative headline inflation. To say nothing of what will be a prolonged period of suppressed energy prices, and the direct as well as indirect feed through low oil prices will have on headline and core inflation metrics.

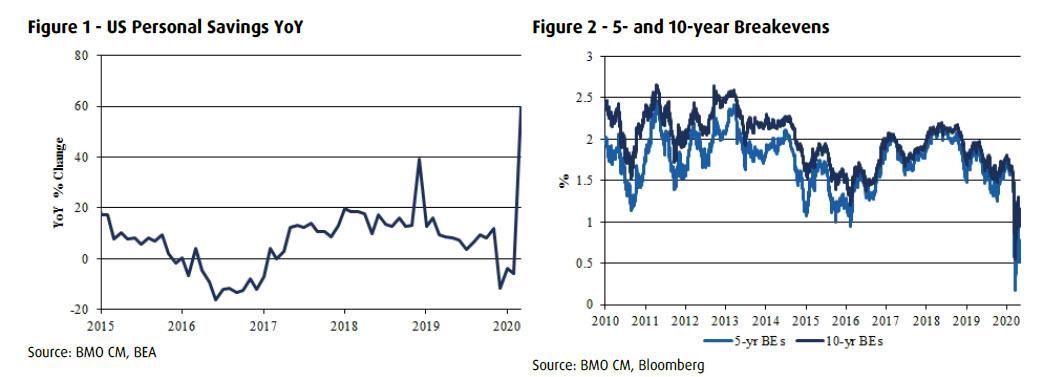

Conversely, the stimulus efforts via the CARES Act, policy rates at the effective lower bound, and the myriad of new Fed programs will assist in accelerating the recovery from the initial wave of contagion and mitigate the depths of any new downside which results from a second or third wave of COVID-19. In practical terms, this will ideally prevent the domestic economy from falling into a deflationary trap. Anecdotally, there is already evidence of a notable subset of the labor force whose bolstered unemployment benefits exceed their pre-pandemic pay. This increased compensation is leading to higher savings by virtue of diminished spending (Figure 1), introducing latent consumption potential that could run up against disrupted supply chains; thus catalyzing an inflationary spike in some consumer goods. We do not anticipate this will play out as confidence will be in question long after the lockdowns are formally lifted.

In terms of the direction of US rates, the economic recovery will intuitively translate to higher long-end yields as inflation expectations begin to return to the Treasury market. With 5- and 10-year breakevens still extremely low by historical standards at 75 bp and 128 bp, there is more room to the upside barring a complete decoupling of inflation expectations from the Fed’s 2% target. This reinforces our anticipation to see 10-year yields finish 2020 back in the land of the 1-handle, while 2-year rates and the front-end of the curve remain anchored to the realities of a lower for longer monetary policy paradigm.

* * *

2. How will heavy COVID-19 related credit issuance impact spreads?

Since March, investment grade corporates have issued $599 bn, making March and April the two heaviest issuance months on record. Expectations for May are around $250-300 bn, indicating heavy supply should continue into summer. If realized, gross issuance through the first five months of the year would be around $1.1 tn, in line with the totals for each of 2018 and 2019. The drivers of this dynamic are straightforward: facing an economic shutdown and a deep recession once the economy reopens, cash needs are elevated. Corporations are burning through cash while businesses are closed and earnings will face a prolonged hit. Further, all-in borrowing costs are fairly low by historical standards (Figure 3). Corporate yields have been aided by various forms of monetary accommodation including rate cuts and QE.

In addition, SSA/agency market issuance is increasing as part of the governmental response to the pandemic. We expect the USD SSA market to grow by $125-$140 bn over the next three years, led by the largest current borrowers, with the majority of growth coming in 2021 and 2022. In the early phases of crisis response, SSAs tend to use liquidity buffers and/or redirect planned expenditures to meet capital needs, with debt ultimately termed out in the ensuing years. On the other hand, US agency debt outstanding grows alongside the crisis response, primarily to fund CARES Act mortgage forbearance. Agency debt outstanding grew $282 bn in March alone, though only $52 bn of that increase was in term debt with FHLB increasing DNs outstanding $200 bn. While net agency issuance in April was negative, we expect it to resume increasing in the months ahead as further forbearance is funded, FHLB advances increase, and March discount note supply is termed out. The peak in forbearance is expected to hit in May as payments were potentially able to be made in March and April.

The impact of this heavy supply on credit spreads is two-fold. First, increased borrowing in the open market and through the various Fed facilities will increase leverage, which is of particular concern in the corporate market. Elevated corporate leverage has been an ongoing theme in the aftermath of the financial crisis, and will be exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Increased debt incurred during this pandemic must be paid out of future earnings, which are likely to be weak even after the economy opens. This could lead to additional downgrades as balance sheets erode.

Second, the technical impact of increased corporate supply will eventually weigh on the market, even if investors do not price to the supply in the near-term. The Fed’s aggressive QE program should counteract the technical headwind to a large degree, even as supply will outpace central bank buying. Quantitative easing in the Treasury market narrows spreads via the portfolio rebalancing effect, in that it pushes investors out the credit curve. The Fed has purchased about $1.46 tn worth of Treasuries since its program began on March 16. And while net Treasury issuance has totaled $1.56 tn over this period, the vast majority of this has been in bills, and it will take time before Treasury fully terms out these borrowing needs. On the other hand, with respect to Fed buying of corporate debt, the current size of the SMCCF is just up to $250 bn. As mentioned, gross issuance in March and April has totaled $550 bn, with May likely to bring another $250-300 bn. While this does not render QE ineffective, it certainly represents a competing technical headwind. In conclusion, this heavy supply is likely to persist, and while it does not represent a near-term headwind in the current environment, it is likely to weigh on the market in the medium-term.

Tyler Durden

Thu, 05/07/2020 – 16:47

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3bfeIMi Tyler Durden