Here’s What Would Happen If The Fed Launched Negative Rates

Tyler Durden

Sat, 05/16/2020 – 17:00

On Thursday, May 7, an unprecedented event took place: after a violent repricing in Eurodollar contracts as near as November 2020, for the first time ever the market was pricing in that negative interest rates are not only coming to the US, but would arrive sometime around the presidential election.

This move prompted a barrage of Fed speakers, including the Fed chair, to remind the public that the Fed really, really, really does not believe in negative rates (but never say never), even though one could say the same thing for the BOJ, the ECB and the SNB… and look at them now. In fact, in a world where growth is only possible with trillions in new debt injections – and with debt already at crushing levels, interest rates have to be as close to zero if not below it – the Fed has emerged as the “rational” outlier that refuses to take rates negative.

And yet, in a world where the economy was already sinking ahead of the catastrophic collapse spawned by the coronavirus, there is only so much the Fed can do before it took is dragged into the NIRP vortex.

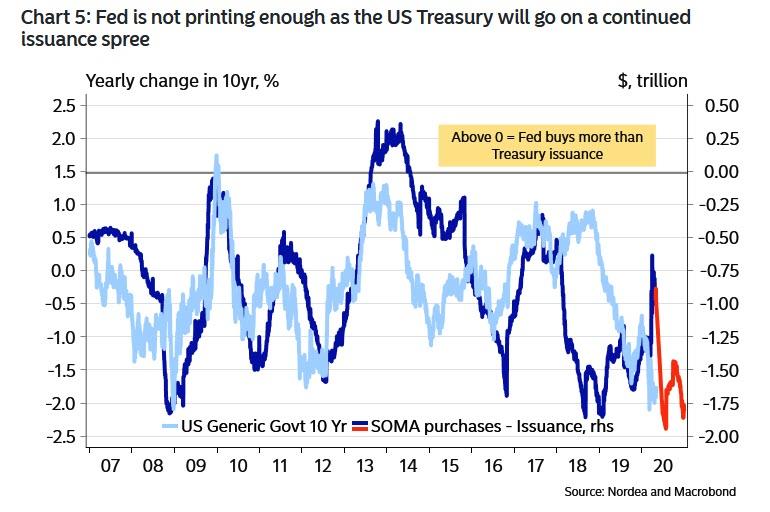

To be sure, in many ways the market’s expectation for negative rates is rational. As we pointed out overnight, even Goldman is concerned that the Fed is simply not doing enough QE to monetize the massive upcoming treasury flood let along stimulate a global reflationary wave, which leaves it with just one other option: negative rates. Nordea’s Andreas Steno Larsen looked at this dynamic and reached a similar conclusion: “the Fed is still not buying enough to fully re-ignite the global credit cycle. We find that the Fed needs to buy a lot of bonds compared to issuance before USD scarcity is finally fully eased in the system, leading to easier financial conditions in EM and ultimately global growth prospects being repriced positively” In other words, “the Fed will have to buy more than currently. This speaks in favour of even LOWER long USD bond yields, not higher.”

The market may also be taking hints from former Minneapolis Fed president, Narayana Kocherlakota who argued in an op-ed that the Fed should take interest rates below zero for the first time ever. To use his words, “unprecedented situations require unprecedented actions”.

On the other hand, there may simply be something in the Minneapolis water that makes local Fed president raving monetary lunatics (here we envision not only Kocherlakota but his successor, former Goldman banker and TARP author, Neel Kashkari), because while it is quite simple to extrapolate the catastrophic experience the Japanese and European financial sectors have had with NIRP to the US, the truth is that the Fed has rarely this unified in any view, and as former Fed staffer and current BofA rates strategist, Mark Cabana writes, “US negative rates are not an attractive monetary policy tool” and Powell was very clear in this view during his videoconference last Wednesday.

As an alternative to negative rates Chair Powell has indicated the Fed can ease through forward guidance, UST & agency MBS asset purchases, or “13-3” extraordinary market programs, although here again we run into the “huge problem” we observed yesterday facing the Fed, that the most likely alternative to NIRP would be a massive expansion in QE (one which Deutsche Bank calculated at over $3 trillion in more QE), yet such a dramatic move would also require – most likely – some sort of market event to give the Fed the cover to take Unlimited QE to a truly unprecedented level. It remains unclear how the Fed will square those two constraints.

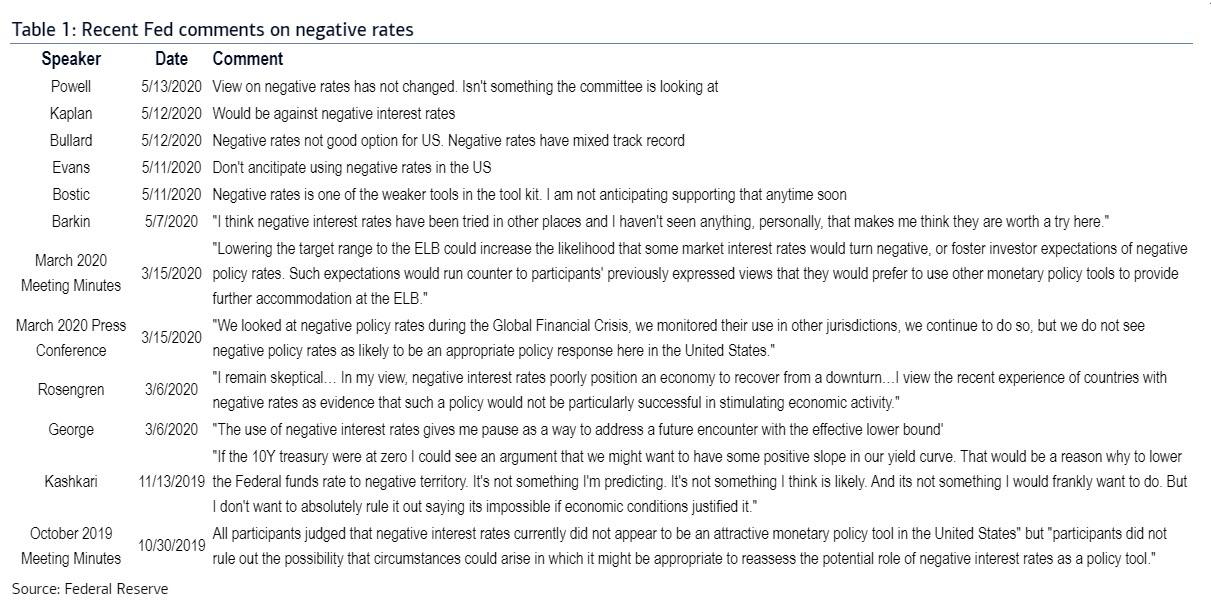

And while Cabana expects Fed official to “overweight” the abovementioned tools in support of expansive fiscal policies “but not shift their thinking on negative interest rates in the near term.” As an aside, for those who have missed the recent “Fed talk”, below is a summary of the uniform and widespread opposition to negative rates from a range of Fed officials.

Of the above, the most striking rebuke of negative rates came from the October 2019 FOMC meeting minutes when “all participants judged that negative interest rates currently did not appear to be an attractive monetary policy tool in the United States”. It is very unusual to see this type of broad based agreement on any potential policy stance, and as BofA concludes, “in order to see a material change in thinking on negative rates it would likely require a leadership change and large scale Fed turnover.” While neither of these is likely in the near term, Trump recent endorsement of negative rates leaves open the door that the president may appoint an even more dovish Fed president in his second term (we are confident that Kashkari would be delighted to be considered for the post of the man who destroys the dollar as the world’s reserve currency).

Operational hurdles: IOER Legality

To be sure, in addition to the Fed’s own preference – which as events in the past two years have shown can change on a dime, especially once a “shock” triggers a violent market meltdown – there are countless operational hurdles, starting with the question of whether negative rates are even legal.

Consider, that in the Federal Reserve Act, it is specifically stated that banks can “receive” interest on reserves. There is no specification for banks paying interest or how negative rates could be implemented in this context.

In her 2016 Semiannual Monetary Policy Report to the House, former Fed Chair Yellen noted that the legality of negative rates “remains a question that we still would need to investigate more thoroughly.” This question has not been definitively answered and it is not clear whether the Fed would actually charge negative interest or implement a fee for holding reserves. Indeed, the fact that the Fed has not ruled out negative rates suggests the Fed likely has adequate legal cover to implement such a regime. Furthermore, while just two months ago one would have argued that it is illegal for the Fed to buy corporate bonds, a quick meeting between Powell and Mnuchin which led to a bizarre joint venture between the Fed and the Treasury changed all that in the blink of an eye. In short, as Cabana writes, “if the Fed wanted to implement negative rates they could find a way to do so but could face pushback. We see this as an important but surmountable hurdle for the Fed to clear before implementing negative rates.”

Treasury auction obstacles

NIRP legality aside, treasury auctions provide another obstacle for bills & nominal coupons.

Treasury nominal coupons and bills: Treasury auction regulations via the “Uniform Offering Circular” state that nominal coupons & bills are permitted only to have a bid rate that is “a positive number or zero”. This is striking since in August 2012 Treasury announced it was in the process of building the operational capabilities to allow for negative rate bidding in Treasury bill auctions. It is thus safe to assume that the Treasury has subsequently built the operational capacity to auction bills and nominal coupons with negative rate bidding but is unwilling to take this capacity live. It is unclear why Treasury might be reluctant to take this step but it could be (1) Treasury is worried about sending a signal about the economic or monetary policy outlook (2) there may be legal or accounting hurdles that need to be cleared up.

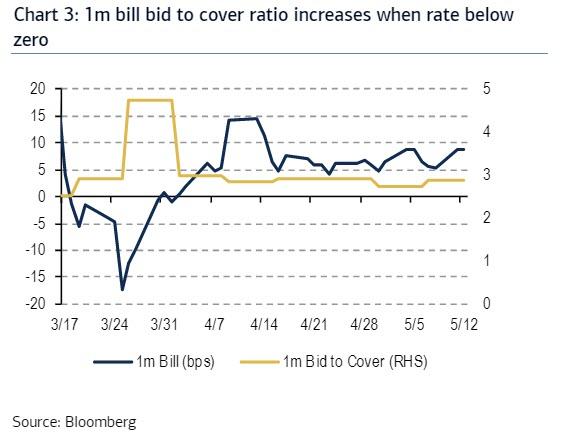

Treasury’s inability to auction bills or nominal coupon securities with negative rates results in an inefficient primary issuance process when secondary market rates are negative. Treasury offers securities at par but bidders can then sell these securities into the secondary market at a premium. This essentially results in a subsidy to the primary dealer or Treasury bidder community that should be captured by the Treasury (we described this in “Here Is The Treasury’s (Not So) Secret Trade Printing Millions In Guaranteed, Risk-Free Profits Every Day“) . Treasury auction rules suggest that when a security is auctioned at par the bidders have their allocations determined on a proportional basis to their auction offers. This is why bid-to-covers spike when secondary market levels are below zero at auction.

TIPS & floating rate notes: Treasury rules state that among fixed rate debt only TIPS can have a negative bid rate. Treasury floating rate debt can be auctioned with a discount margin that may be positive, negative, or zero but there is a 0% minimum on interest accrual. Treasury rules ensure that an investor is never required to pay the US Treasury during a period of CPI deflation or during any future period in which bills might be auctioned at negative rates.

That said, just like the legality issue, BofA does not see Treasury auction limitations as a material constraint to adopting negative rates “since we assume operational hurdles can easily be overcome. However, allowing negative UST bidding for bills and nominal coupons is another important operational hurdle that will need to be addressed before negative rates can be more widely adopted.”

Money Market Funds in a negative rate environment

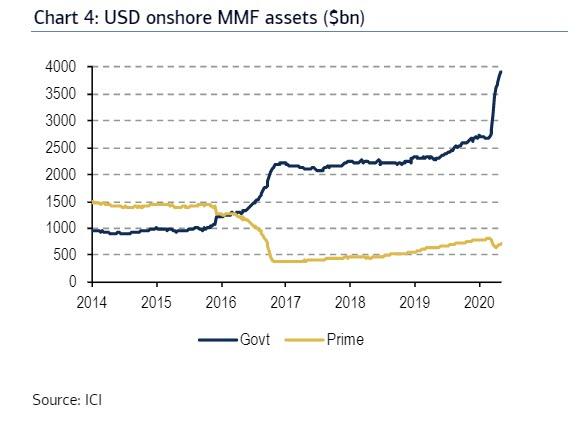

Ass Cabana continues, a key concern around negative rates in the US is the viability of money market funds (MMFs). MMF AUM total $4.8tn with the vast majority in government funds. MMFs also play an important role in funding, making up ~25% of all cash lending in repo markets.

Negative rates are particularly problematic for stable NAV MMF. Recall, 2a-7 MMF reform requires institutional prime & municipal have floating NAV while government and retail prime + muni funds have $1 stable NAVs. Negative rates are an issue for stable NAV funds because the fund value will decline by virtue of investing in negative yielding assets. To address this NAV stability in a negative rate environment MMFs in the US would need to move to a floating NAV regime, potentially increase customer fees, or use a share cancellation regime. The latter two options as more likely given that changes in the stable NAV structure could potentially cause sudden changes in fund allocation as we saw during the 2016 MMF reform

Increased MMF customer fees or a share cancellation regime are more likely in a negative rate environment vs a shift to floating NAV for all funds. In a regime with higher MMF customer fees the stable $1 NAV could still be retained but the principal invested in the fund would gradually be reduced by the fees charges to compensate the fund for the negative yielding securities. In a share cancellation regime a MMF would retain the $1 stable NAV but gradually reduce the number of shares an investor is entitled to at redemption. For example, an investor that deposits $100 and receives 100 MMF shares in a -1% negative rate environment would see their shares gradually cancelled; 1Y later they would receive $99 in cash at redemption.

Depending on the implementation of negative rates in the US, MMFs may also face competition with deposits. If the Fed sets IOER negative this will immediately impact market rates, but may not be passed onto consumers. Banks may charge fees or other service costs in order to offset their negative IOER rate. This could prompt outflows from MMFs into deposits, which are often considered close alternatives. As a result, tetail MMF investors would be the most likely to shift to bank deposits given reluctance in the banking industry to charge negative deposit rates for retail consumers.

BofA’s bottom line is that the US MMF industry would likely be able to adapt to a regime of negative yielding interest rates if given enough time to prepare. That said, MMFs and front end investors would likely need at least 6m to 1Y worth of notification from the Fed that negative rates should be prepared for so that they could properly adjust their systems. Ominously, Cabana says that his “sense is that several MMF are already preparing for the possibility of negative rates.”

Other issues: systems & repo

The take home from the above, is that if the Fed were to take rates negative, Cabana is confident that it would need to provide ample lead time to the market to prepare financial systems for such a change. Market participants would also need to adjust trading, settlement, accounting, tax, and legal systems or procedures to prepare for negative rate trading. While some of these operational hurdles have already been cleared for large global firms given the periodic negative rate trading of US Treasuries and other developed market sovereign bonds, more time would be needed to prepare for domestically oriented firms. Furthermore, the Fed would likely prefer that firms focus their operational resources on preparing for the transition away from LIBOR rather than on negative rates, which may further limit the Fed’s willingness to take rates negative in the near term.

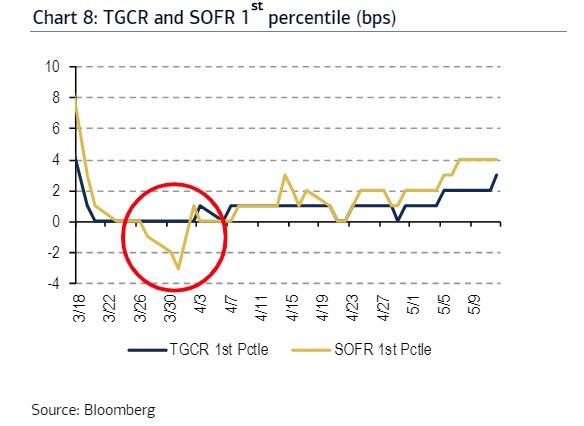

One area where Cabana does have serious questions on the operational readiness for negative rates is in the repo market. This is not an issue for specific issue UST collateral, which has frequently traded at negative rates post UST fails charge in 2009, but rather is a question centered on the tri-party repo market where it is unclear if there is operational capacity for rates to trade at negative levels. Questions emerged given that in late March the 1st percentile of the SOFR rates traded in negative territory while the 1st percentile of tri-party general collateral repo rate (TGCR) remained at zero. This was the first time this segment of low-rate TGCR trades exceeded SOFR

If this is correct, and there are operational issues with taking tri-party GC repo into negative territory, then this is a material operational impediment, and as Cabana writes, “we cannot envision the Fed moving into negative territory until the tri-party repo market can easily follow suit.”

Negative rates can hamper financial intermediation

The biggest problem, however, is that the scope of negative rates is ultimately limited. As a reminder, in a 2010 Federal Reserve memo, it was noted that setting IOER lower than about -35bps would likely cause banks to reduce their reserve holdings and hold currency instead. However, other central banks such as the SNB and ECB have taken rates more deeply negative, suggesting that -35bp is not a firm floor.

Meanwhile, as rates become negative there are also other behavioral shifts that could arise, according to BofA, which notes that if banks begin to charge depositors, it is possible that cash vault holdings would increase or that special banks could be formed to store physical currency. Consumers and businesses might also seek to pre-pay credit card, account payable, or tax bills in order to reduce their cash holdings. Similarly, those who are expecting payments from creditworthy entities might prefer to defer them while those receiving checks might wait longer periods before depositing them. It is unlikely that the Fed would find such behavioral shifts productive and might view them as an additional cost to negative interest rates.

On top of all that, negative rates would serve to impede key financial intermediation functions for banks, pensions, & insurers. As we have observed in Europe and Japan, negative interest rates would hurt bank profitability and potentially make them less willing lenders due to lower capital cushions.

Virtually every strategist has warned of significant downside to bank earnings in a negative rate environment and noted lower margins result in reduced capacity for a bank to absorb losses. Pensions & insurers would also struggle with larger liabilities to manage. Financial intermediation complications likely reduce the attractiveness of negative US rates for the Fed.

Overall, Fed officials have suggested that financial intermediation issues are a meaningful constraint on their willingness to consider negative rates. Financial intermediation + operational challenges likely reinforce the Fed’s poor cost/benefit assessment of negative rates.

* * *

Aside from Bank of America’s near universal panning of negative rates, JPMorgan’s Nick Panigirtzoglou is similarly damning of what the financial system would look like if the Fed shifts to a negative rate.

Starting with the negative impacts first, JPMorgan’s strategist has “little doubt” that US interbank markets and repo markets would suffer if the Fed cuts its policy rate to negative. Given money market funds are important participants in repo markets, overall repo market activity could decline. This is also because narrowing spreads in the repo market are likely to induce some lenders of collateral to pull back from the market, on the grounds that returns from securities lending are no longer adequate. That would impair bond market liquidity, by making it more difficult to cover short positions in repo.

Incentives to cover shorts are also reduced at zero rates, which can result in higher fail volumes than seen before, hampering liquidity and volumes even further. Finally, and echoing Cabana’s concerns above, some US counterparties (mainly US real money investors) may not be able to trade repo at negative levels (operational, legal, economic reasons etc.) which will again likely reduce repo market volume/activity.

Separately, similar to what happened after the ECB depo rate cut in June 2014, mildly negative US rates coupled with a natural aversion to negative rates will likely reduce the incentive of healthier banks to trade with each other and increase their incentive to trade with less healthy banks including US subsidiaries of foreign banks. That is, even if US interbank market volumes decline, a greater portion of the interbank volume is likely to involve less healthy banks. Similarly a greater portion of US repo markets should involve higher yielding non-government collateral. That is, interbank markets, both unsecured and secured, will likely become less fragmented as it happened in the euro area post June 2014.

The search for yield will likely also spread from money markets to bond markets. As the US money market fund industry gets hurt, the main beneficiary would be US bond funds, i.e. investors would replace money funds with bond funds as savings vehicles. And as, following a Fed policy rate cut to negative, the short end of the US government bond market collapses towards zero, this would force bond investors towards higher maturity and lower-quality debt instruments.

Negative rates would also result in an even bigger bond bubble, as corporate and mortgage bonds would be the biggest beneficiaries of this intense search for yield given their relatively low risk weighting and given that banks with large reserve deposits at the Fed would likely face intense pressure to avoid the capital erosion from negative deposit rates.

While negative interest rates on deposits would incentivize banks to “get rid” of their excess deposits rather than suffer an erosion of capital, the amount of reserves in the system can only be reduced if the Fed starts reducing its bond holdings, something unthinkable in the current conjuncture. If a commercial bank makes a loan or buys a bond to avoid negative rates, they simply pass reserves on to another bank, which ultimately end up back at the Fed. As such, excess reserves would become something of a ‘hot potato’, with no bank wanting to hold lots of them at the end of the day. And this “hot potato” effect would be even more intense in the current backdrop of central bank balance sheet expansion and higher liquidity.

The likely damage to the profitability of banks and the risk that banks could actually increase lending rates to protect their interest rate margins. That is, assuming that banks will be reluctant to pass negative rates to retail or corporate depositors, they might increase lending rates to offset the decline in their profitability. Effectively, a decline in the deposit rate to negative could actually cause a tightening in financial conditions in the real economy and a contraction in bank lending rather than easing.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2LAzpYM Tyler Durden