As China Fumes Over Trump’s “Gross Interference” In Hong Kong, Here Are 6 Things It Can Do In Retaliation

Tyler Durden

Sun, 05/31/2020 – 22:30

Following Trump’s Friday announcement of watered-down measures against China and Hong Kong, which included stripping Hong Kong of some of its privileged trade status as a result of Beijing’s crackdown on the island and threatening to kick out select Chinese students but falling well short of a “nuclear option” including sanctions on individuals and institutions and the expulsion of Chinese banks from SWIFT, Hong Kong’s government said actions threatened by President Donald Trump are “unjustified” and repeated that China is within its “legitimate rights” to pursue new national security laws that Beijing says will help quell months of unrest.

The People’s Daily, the official mouthpiece of China’s Communist Party, wrote that the plans outlined by Trump at the White House on Friday were “gross interference” in Beijing’s affairs and were “doomed to fail.” In a second commentary published Sunday on its front page, the newspaper accused the U.S. and Western politicians of “double standards” and “shameless hegemony” for their criticism of the legislation. Meanwhile, China’s ambassador to the U.S. wrote in a Bloomberg Opinion editorial that the central government has the ultimate responsibility for upholding national security in Hong Kong, and that the proposed legislation “will protect law-abiding citizens.”

And while Trump was widely seen as conserving ammo for future potential escalations, the market stormed higher on Friday amid optimism that the US president does not intend to pursue a more aggressive response over China’s de facto take over of Hong Kong. In fact, officials from Hong Kong wrote in a 949-word statement that they’re “not unduly worried” about the sanctions and trade restrictions proposed by Trump.

Hong Kong will continue to rely on rule of law, judicial independence, and a free and open trade policy, according to a statement issued Saturday evening local time.

The proposed legislation “does not give rise to fears of the loss of liberties by its people that will warrant international debate or interference by another country” and such fears are “simply fallacious,” the Hong Kong government said in its statement.

“We note with deep regret that President Trump and his administration continue to smear and demonize the legitimate rights and duty of our sovereign to safeguard national security in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region which in turn is aimed at restoring stability to Hong Kong society,” the statement said.

Cui Tiankai, China’s U.S. ambassador, wrote on Saturday that Hong Kong was “a romantic fusion of the East and the West.”

“To our regret, such romance is evaporating,” the envoy wrote. The violent actions of protesters against police, citizens and property there there had crossed “a red line” for Beijing, he said. “Hong Kong is in disarray. China’s national security is at risk. That is why the central government has chosen to act.”

China’s rubber-stamp legislature on Thursday approved a proposal for sweeping new national security laws for Hong Kong, but it could take Chinese officials months to sort out details of laws banning subversion, secession, terrorism and foreign interference.

Meanwhile, the People’s Daily again underscored that China would be firm in responding to any U.S. moves, without specifying what actions Beijing might take. In Sunday’s commentary it said the proposed legislation is a rightful move to defend China’s sovereignty and compatible with international practice.

* * *

So what actions might Chinese policymakers take to deter these shifts in US policy, or in response to them?

According to Goldman’s economist Alec Philips, Chinese policymakers will take a somewhat reactive stance to US criticisms and demands on trade and other issues, at least publicly, in an effort not to escalate tensions. However, the forcefulness of the response could vary depending on how closely US actions strike at China’s strategic interests, and whether practical retaliation options exist that appear proportional and do not escalate frictions. For trade issues, the 2018-19 playbook of imposing retaliation only after the US has actually changed policy, and even then responding proportionately or slightly less than proportionately, will likely remain in force. Some possible retaliatory actions from Chinese policymakers in trade and other areas could include:

- Trade sanctions or tariffs on US exports. This particular Chinese response seems most likely in the event of a phase 1 deal breakdown. This was China’s response of choice during the trade war, although the scale of the response was typically less-than-proportional, reflecting both a desire to limit escalation and the smaller amount of US exports to China. If the trade deal were to break down and the Trump administration increased tariffs on China, expect to see a Chinese response of this type. (In theory, China also could conceivably impose formal or informal constraints on Chinese buying of US goods or “service exports” e.g. limit tourism or the flow of students studying in the US, as we have seen occur with some other regional trading partners in the context of political frictions–e.g. Chinese group tourism fell off sharply in Korea in 2017. However, such a response would have little impact at present given that tourism and international education have collapsed amid COVID-19.) It is doubtful that tariffs would be used as a response to other US actions beyond trade.

- Actions against US companies operating in China. US sanctions on Huawei recently expanded to include foreign companies selling a “direct product” of US technology, e.g. semiconductor chips made using US equipment. In response, Chinese policymakers might take actions unfavorable to US firms in China. These could include regulatory measures that complicate or prevent operation of a business. Chinese policymakers originally mooted the concept of an “unreliable entities list” about a year ago in the context of sanctions on Huawei and other Chinese companies; though it is unclear precisely what the consequences of being labeled “unreliable” would imply, presumably it would be very detrimental for sales within China. Retaliating in this way is not without cost: it could undermine policymakers’ efforts to present China as an attractive investment destination. It would also be outside WTO norms and could undermine China’s case for relief in that body.

- Export restrictions. Another possible response to US sanctions on particular companies, or other US actions constraining supplies to China, could be restrictions of Chinese exports to the United States. Rare earth minerals have been frequently cited in this context. China is a dominant supplier and substitution using other materials is difficult, so if China were to decide to restrict exports of rare earths to the US the effect could be significant. Indeed, Chinese state media threatened supply restrictions on rare earths following the initial round of sanctions on Huawei last year. That threat has prompted the US government to take measures to develop rare earth production and refining capacity in the United States. Another very sensitive area could be medical equipment and supplies, which are in great demand around the world given the coronavirus crisis, and where the US sources significant amounts from China. But the perception issues around curtailing supplies in this area would be significant, and third countries could potentially re-route such goods to the United States.

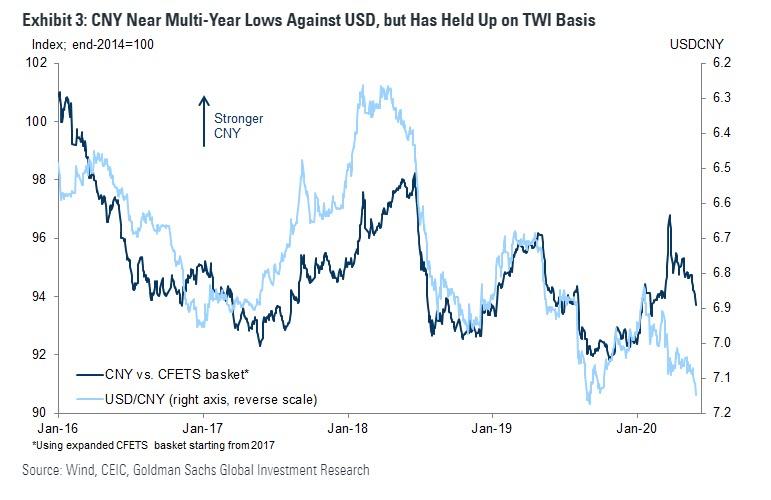

- Exchange rate depreciation. Chinese policymakers could choose to more readily accept currency depreciation, or even take active steps (such as weaker USDCNY fixings) to encourage it. Currently, the CNY is trading near multi-year lows against the USD but at more moderate levels against the CFETS currency basket…

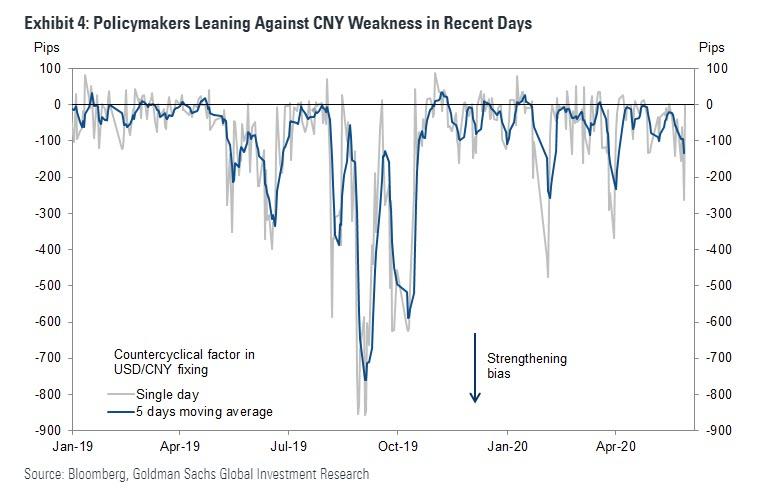

… reflecting broad USD strength. In recent days, policymakers have signaled moderate resistance to further depreciation by setting the daily USDCNY fixing stronger than other factors would imply.

Currency weakness might help exports on the margin, but could also intensify capital outflow pressures; although policymakers appear to have quite good control of the capital account following the chastening experience of volatility in 2015-16, their appetite for experimentation in this area is likely limited. We think the chance of an engineered depreciation is very small, though policymakers would likely accept some modest depreciation if tensions continue to intensify, especially if there were a breakdown in the trade deal or a major increase in capital outflow pressures. - Large-scale sales of US asset holdings. At times of friction, the notion that China might sell its large holdings in US government securities as retaliation for trade actions surfaces in media commentary. (The latest Treasury International Capital data show Chinese holdings of $1.08 trn in US Treasuries as of the end of March, which are almost entirely from the official sector as China holds roughly $3 trn in FX reserves; in addition, agency holdings are on the order of $200bn and there could be additional assets held via custodians in other countries). For their part, US policymakers seem to have briefly entertained, but quickly discarded, the idea of trying to extract payment for damages related to the coronavirus from China’s holdings of Treasury debt. Here Goldman views disruptive actions by either the US or China in this area as unlikely. Abrupt large sales of Treasury securities or other US assets could tighten financial conditions well beyond the United States, so would appear an unattractive approach for Chinese policymakers for both political and economic reasons. However, a gradual reduction of US securities in the portfolios of SAFE and CIC is certainly a possibility-as overall reserve assets have been essentially flat, and the portfolio appears overweight US assets relative to trade weights. In fact, Chinese holdings of US debt have been unchanged for years, and while China is not dumping its TSY holdings, it certainly isn’t adding to them. Chinese policymakers might also choose to reduce the duration of their government securities holdings, which at least on the margin would push up long-term interest rates. Having said that, even a meaningful re-weighting of Chinese official assets out of US securities (say 5% of China’s total reserve assets per year or $150bn) would be small in comparison to the recent ramp-up in asset purchases by the Federal Reserve.

- Change in stance on geopolitical issues of concern to the United States. President Trump has in the past linked trade policy to foreign policy in his comments, for example in the case of China’s cooperation in managing North Korea’s nuclear ambitions. For example, in December 2018 he explained “I have been soft on China because the only thing more important to me than trade is war…If they’re helping me with North Korea, I can look at trade a little bit differently, at least for a period of time. And that’s what I’ve been doing. ” More generally, Chinese policymakers could choose to be more, or less, helpful in regard to geopolitical issues of interest to the United States as US policies towards China change. This sort of cooperation would presumably be evident to the intelligence community and senior US policymakers, but not necessarily to markets or the general public.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3eOAIjp Tyler Durden