As China PMI Disappoints, Another Major Problem Emerges

Tyler Durden

Sun, 05/31/2020 – 21:30

Overnight, China’s NBS reported that in May, manufacturing PMI signaled a continued recovery in factory activity, albeit at a slower pace than in April and below expectations (50.6, exp.51.0, down from 50.8). Sub-indexes in the manufacturing surveys suggest export order sub-index remained weak and employment deteriorated further.

Of note, the manufacturing employment sub-index weakened to 49.4 from 50.2, implying continued deterioration in the labor market. On the other hand, inventory indicators suggested a destocking trend, with raw material inventories declining to 47.3 from 48.2, and the finished goods inventory sub-index declined to 47.3 from 49.3 in April.

Yet even as China’s factories are starting to hum again, a new problem is emerging as executives are now worried that the rebound could falter on weak demand both at home but especially abroad, something we warned about some time ago when we warned that China’s push to produce at all costs will eventually backfire.

Justin Yu, a sales manager at Zhejiang-based Pinghu Mijia Child Product that makes toy scooters sold for American retailers, is among those seeing their order book improve from the depths of the coronavirus lockdown, but remain well below normal.

Quoted by Bloomberg, Yu said that “we are seeing more orders coming in this month as we get closer to our normal peak season,” Yu said. “But our orders are still 40-50% lower than last year.” The factory’s production capacity is running at about 70% to 80%, and Yu is making to order to avoid any build up in stock.

The disconnect between China’s recovering production and still dormant demand had shown up in data revealing a rise in inventories and once again contradicting the official PMI numbers which as noted above, show that to be easing. China’s fake data aside, the worry remains that sustained overproduction will lead China’s factories to keep cutting prices, compounding global deflationary headwinds and worsening trade tensions, before they eventually cut back on production and therefore even more jobs.

“The supply normalization has already outpaced demand recovery,” said Yao Wei, China economist at Societe Generale SA. “In other words, the recovery so far is a deflationary recovery.”

Which is another way of saying it is not a recovery at all, and the US, whose economy remains largely shut is not helping.

So given the weak export outlook, manufacturers such as Fujian Strait Textile Technology are switching their business models to target the home market, according to Bloomberg. It used to sell 60% of its products to Europe and the U.S. before the coronavirus crisis wiped out those sales. Now, Dong Liu, the company’s vice president, is looking for opportunities at home.

“Our company executives have started to visit the local market to make more potential clients know about us,” he said. “Since May 26, we have been producing 24 hours everyday at full capacity. All the inventory has already been sold and we’re rushing to make goods.”

Alas, the domestic-focused strategy also has numerous drawbacks: while China’s consumers are largely free to resume their regular lives as fresh virus cases slow to a trickle, they too aren’t spending like they used to (almost as if they also don’t believe Beijing’s solemn vows that everything is back to normal): retail sales slid 7.5% in April, more than the projected 6% drop. Restaurant and catering receipts slumped by 31.1% from a year earlier, after a 46.8% collapse in March.

“Although demand conditions are improving on the margin, they will still take a long time to recover to where they were before the virus crisis. Investment is picking up, domestic consumption improving and external demand is less bad than it was” said Chang Shu, analyst at Bloomberg Economics. The question, of course, is how much time.

In Zhenjiang, Jiangsu province, Melissa Shu, an export manager for an LED car lighting factory, said although orders are steadily improving, there’s no sense of urgency from her clients and the outlook remains uncertain. “We’re just making goods slowly,” Shu said. “We are worried about the coming months.”

* * *

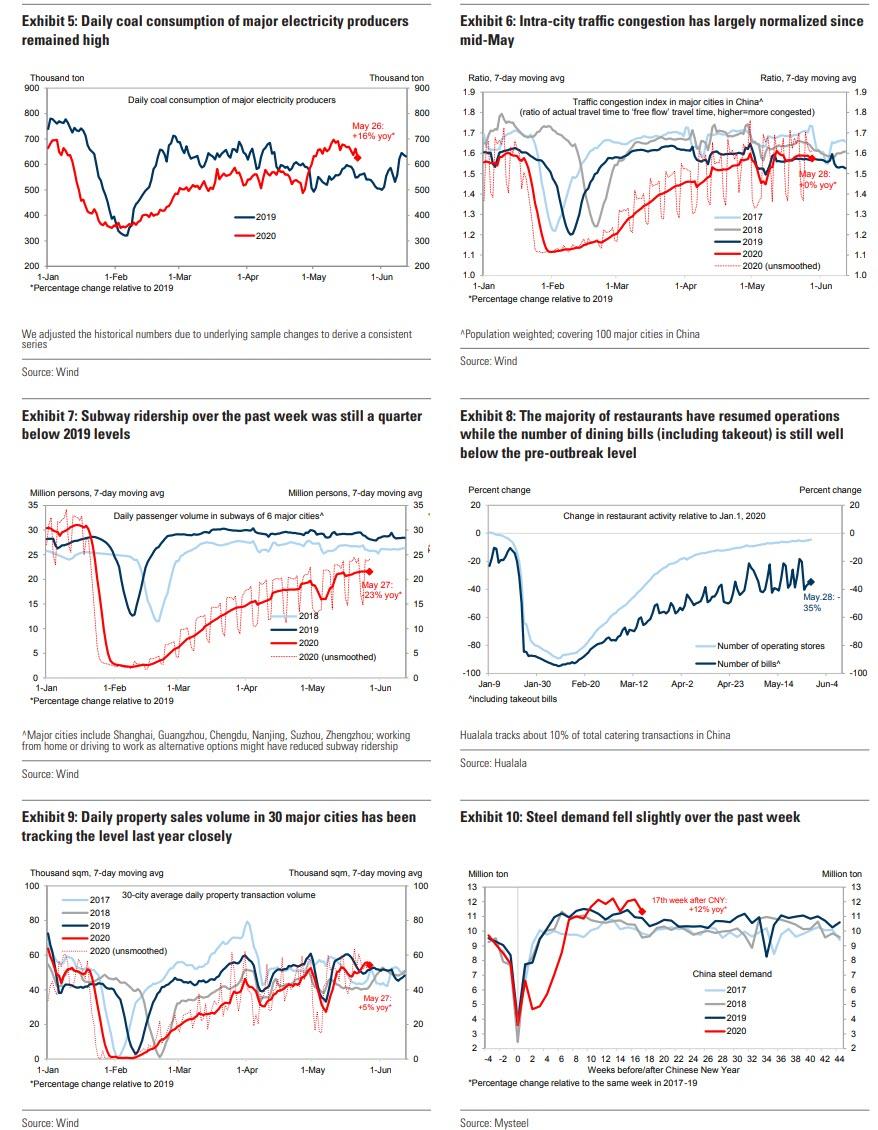

As Bloomberg speculates, some producers may be hoping for a real-life enactment of Say’s law, a part of economic theory which suggests that ultimately supply will create its own demand, as long as prices and wages are flexible, although in China where every datapoint is manipulated and fake, nobody really knows what the current state of the economy is. Various real-time indicators continue to pain a mixed picture.

Another scenario proposed by UBS is that industry self-corrects adversely. The bank’s chief China Economist Wang Tao points to strong steel production during the depths of the coronavirus lockdown, even when demand was weak. Higher inventories means that even as demand recovers, steel production won’t show much of a pick up. And once producers know that orders are falling, they will adjust output.

“I do not think supply will outstrip demand for long – once inventories build up, or producers know orders are falling, production will come down as well,” she said.

Should unemployment continue rising, that could trigger a very messy feedback loop. Premier Li Keqiang in a press conference on Thursday highlighted job creation as a critical priority for the government. The urgency to create jobs may mean there’s even less likelihood of a shake up of state owned companies in the heavy industrial sectors that have historically fueled excess production. It also means that even more ghost cities may be coming.

The disconnect is already clear in data points that show, for example, stronger coal consumption by power plants and rising blast furnace operating rates by steel mills, while at the same time gauges for property and car sales are improving more slowly. That combination, according to Bloomberg, will drag on China’s growth over the coming months, according to economists at Citigroup.

The problem for China’s industrial sector is that it really needs both local and global demand to be strong. If both are weak, and only the government is “injecting” support, it’s a dire outlook. But if local demand recovers and global demand doesn’t, there are still problems.

The best summary of China’s “big problem” came from Viktor Shvets, head of Asian strategy at Macquarie Commodities and Global Markets: “At the end of the day, China’s economy is driven by demand and right now there is no demand,”

A scenario where manufacturers capacity originally dedicated to the export market is retooled to produce for the home market instead would still lead to overproduction. Then the supply-demand mismatch would end up adding to deflationary pressures and a pose fresh headwinds to economic growth, according to Bo Zhuang, chief China economist at research firm TS Lombard.

For now, China’s factory owners are hoping that won’t happen but their optimism is waning fast.

Grace Gao, an export manager at Shandong Pangu Industrial that makes tools like hammers and axes – around 60% of their goods go to Europe – is seeing orders come in as her clients get up and running again. But even as things pick up, Gao remains hesitant to call a full recovery. “Our clients are facing unprecedented problems,” she said. “It’s still hard to estimate when we’ll get back on our feet.”

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/36YUJ45 Tyler Durden