Absentee Ownership: How Amazon, Facebook, & Google Ruin Commerce Without Noticing

Tyler Durden

Tue, 07/28/2020 – 19:15

Authored by Matt Stoller via BIG,

Welcome to BIG, a newsletter about the politics of monopoly and finance. If you’d like to sign up, you can do so here. Or just read on…

Three housekeeping items. First, a colleague and I wrote up for Politico a piece on the American tradition of taking on monopoly power, going all the way back to the 1600s. Second, I co-authored a report explaining how Amazon acquired its market power and the list of laws that need reform to make the corporation safe for democracy. Third, there is another antitrust suit against the cheer monopolist Varsity Brands. If you’re in that world, there’s more info at: https://www.takebackcheer.com

Tomorrow, the CEOs of Apple, Google, Facebook, and Amazon will testify before the House Antitrust Subcommittee. If done right, this hearing could be the most important hearing on monopoly power in decades. So today, in preparation, I’m going to write about how big tech regulates American commerce, using some stories I worked on over the past few weeks.

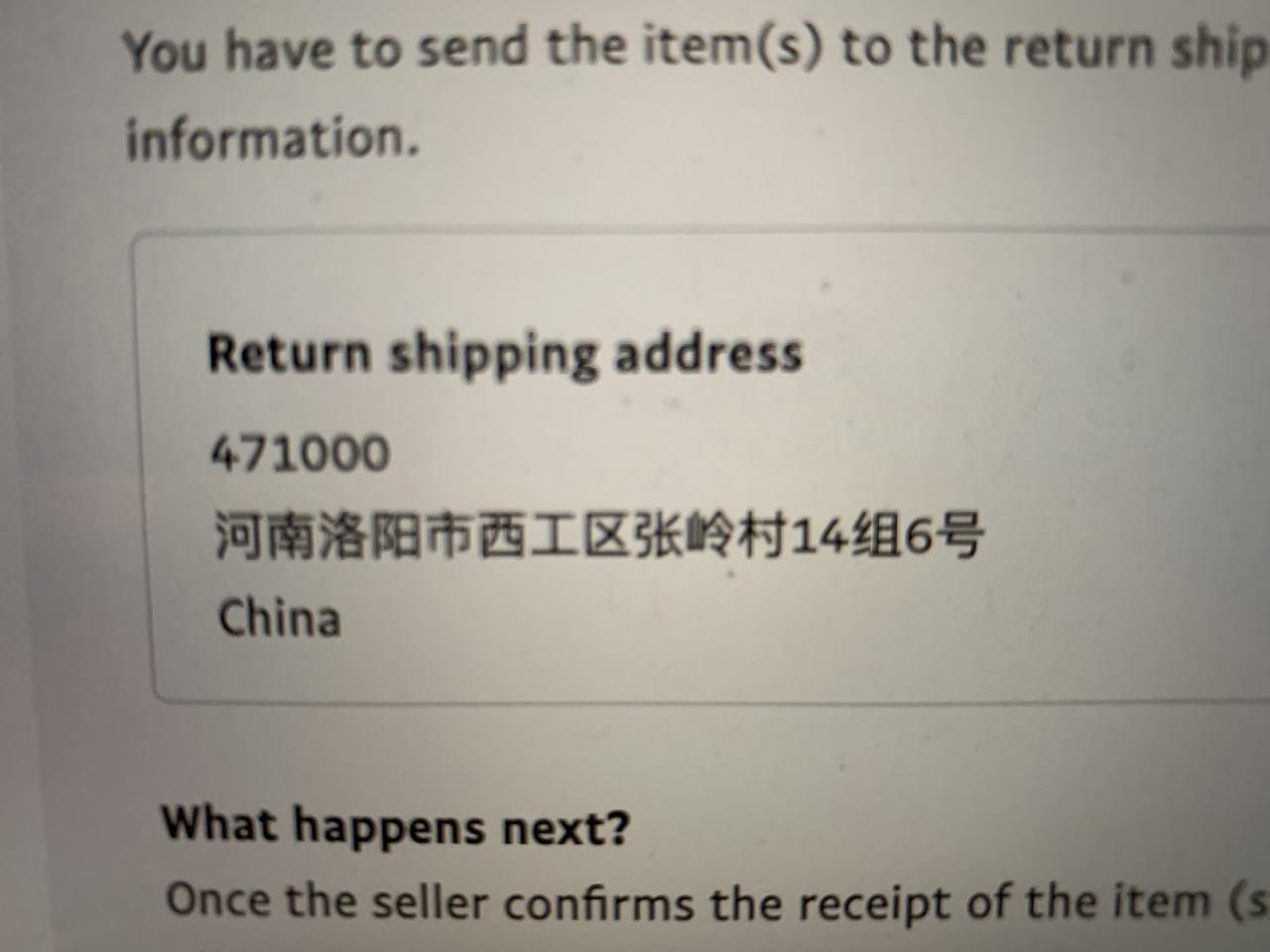

And now… let’s start with a weird picture of a Chinese return address…

Facebook, Google, and Counterfeiting

Last week, I got an email from a frustrated customer of the luxury shoe brand Rothy. “On Memorial Day weekend,” she wrote. “I was on Facebook and there was a sale on my favorite shoe brand, Rothy. The sponsored advertisement said Rothy so I clicked on it and ordered 2 pairs of shoes. When they arrived a few days later, I immediately knew they were counterfeit shoes. I went onto Paypal and requested a refund. A few days later, I received a response that I have to return them to China in order to provide a refund. The return address was in complete Chinese characters. How do Americans write 12 chinese characters?”

Rothy’s is a high quality branded women’s apparel company focusing on sustainability. Rothy shoes and bags are well-made, and the company charges a reasonably high price for them, a price chosen to convey that the Rothy brand means quality. It does not, as a rule, ever put its shoes on sale. I went back and forth with this customer, and she told me that she had called Rothy to complain, and “they shared that they are getting hammered by fraud on Facebook and Instagram but can’t get these goliaths to stop it.”

Such a high quality brand offers an enticing target for Chinese counterfeiters, who have found the perfect criminal accomplice: Facebook. Chinese counterfeiters are buying ads offering Rothy’s shoes for a low price, and directing people to fake websites. People then buy the shoes, which are counterfeit, and customers then complain to Rothy’s. Facebook does take fake ads down, but it is reactive, not proactive about doing so. Rothy’s is in a constant whack-a-mole trying to find the fake ads so they can get Facebook to act.

It gets even more interesting when you throw the Facebook ad boycott into the mix. A few weeks ago, Rothy’s, like a lot of companies, pulled its ads from Facebook in solidarity with Black Lives Matter over Mark Zuckerberg’s policies around hate speech. Many companies did so, which had an interesting effect on ad prices. Facebook ad prices are done on an auction model, which means that high ad demand pushes prices up, and low ad demand pushes them down. With a boycott going on from advertisers, ad prices on that particular day were likely lower than usual. With no Rothy ads on Facebook and Instagram, and low ad prices, Chinese counterfeiters took advantage, and Facebook and Instagram were full of ads for fake Rothy’s. In other words, intentionally or not, Facebook damaged Rothy’s business by allowing counterfeiters to steal the company’s brand equity when the company sought to make a political point with its ad spending.

Why does Facebook enable such scams? It’s simple. The law lets Facebook make a lot of money enabling counterfeiting. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act immunizes Facebook from any consequences for the content of ads bought on their platform; they can’t be sued for facilitating fraud and counterfeiting, so they don’t have any incentive to do anything about it. With no one at Facebook actually paying attention to the scam artists who are buying these ads, scams proliferate.

Contrast ad buying on Facebook with that of television ad purchases. Facebook’s ad sales are automated; anyone can just open a Facebook ad account and start buying advertising, with no third party audits on who is seeing the ad or where that ad is directing people. When you buy a television ad, by contrast, the process involves people at the TV networks interacting with ad agencies, as well as third party auditing through tracking companies. The automating of the ad buying process enables Facebook to have a higher profit margin, because they don’t have to hire anyone to vet advertising sales, especially when ad buyers are using small amounts of money. It also enables straightforward fraud.

Lest you think such negligence or bad behavior by Facebook is a one-off, automated ad systems run by both Facebook and Google routinely enable such brand destruction. Costco, for instance, has had to deal with fake coupons passed around on Facebook. Here’s what that fake coupon looked like:

So has Krogers, which had to deal with a counterfeit ad promoting a fake contest for free groceries.

Thank you for reporting this. This giveaway is fraudulent. Please do not click on it or provide any personal information. Our digital team is aware of this issue and is investigating. Thank you for bringing this to our attention.

— Kroger (@kroger) December 26, 2019

Scammers regularly rip off Kickstarter products, as Matt Binder on Mashable reported last year. “Scammers find an interesting or popular product from crowdfunding sites such as Kickstarter or Indiegogo, rip the item’s details, photos, and videos, and push them via Facebook ads as their own products,” Binder wrote. “Victims of the fraud are either never sent the product or receive a knockoff version.:

This dynamic involved something an early 20th century economist named Thorstein Veblen called “Absentee Ownership,” which is when the locus of control and the locus of responsibility are different. Facebook isn’t legally responsible for the consequences of what goes up on its network, but it still has control over what goes up on its network. Meanwhile, Rothy’s has responsibility for its brand, but no control over how Facebook sells advertising by counterfeiters exploiting its brand.

The same incentives apply to Google, which has earned millions of dollars from companies selling fake health care plans, and has allowed advertisers to put up ads for fake customer service for Netflix as well as fake Microsoft Windows support. (Amazon has its own counterfeiting problem, which the Department of Homeland Security noted awhile back.)

Ultimately, fraud and counterfeiting destroy commerce, and make it impossible for people to create branded goods. There are two legal drivers of absentee ownership that enable this kind of bad behavior. The first is Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which immunizes these platforms from legal liability for enabling fraud and counterfeiting. (Incidentally, Senator Josh Hawley just introduced a bill today to strip this liability protection from companies that sell targeted ads, aka Google and Facebook, and that would solve this problem). The second is the refusal to enforce antitrust law; Facebook’s purchase of Instagram means that a potential competitor to Facebook was taken out of commission. It is possible Instagram might have tried to compete for ad dollars by promising a safer space for advertising, but since Zuckerberg bought this nascent competitor, Instagram never ended up being able to create a differentiated offering.

Monopolies are bad, but monopolies who don’t have to take responsibility for what they destroy are even worse.

So that’s story one, here’s story two.

“I’m from Amazon and I’m here to help.”

A few weeks ago, I got an email from a shoe retailer who told me about something odd happening with Amazon. He told me that his Amazon sales, which had been generally a high turnover reasonable business, were suddenly down 40%. He uses Amazon’s warehousing and logistics business, which is called Fulfillment by Amazon, which meant Amazon took care of making sure that his inventory got to customers.

Only, now that there were fewer sales, inventory began piling up, and he started getting warnings from Amazon that his metrics were below their standards and he was in jeopardy of losing storage capacity for the upcoming holiday season. This kind of million dollar penalty happens often among merchants who sell on Amazon, often randomly and for no discernible reason.

Increases or decreases in sales are a regular topic on the Amazon Seller Forums for merchants who have to sell through its Marketplace. Sometimes Amazon changes its algorithms or features for business reasons. But often stuff just breaks, and no one bothers to fix it. It’s hard to conceptualize this if you’ve never sold through Amazon, because as a consumer, the experience is generally good. But if Amazon has market power over you, the experience is one of hostile neglect. As one merchant put it:

Never expect Amazon to fix broken features unless it will add to their bottom line or the media get involved. Sometimes Amazon acts like that passive boyfriend who never really breaks up with you, they just ghost you until you give up. That is why some features/functions “break” and how much of Amazon’s seller support works.

Over the course of a week and a half, I tried to figure out what was going on with this Amazon algorithm change. It was a fascinating experience. At first, I thought it was an intentional conspiracy by Amazon, where Amazon was trying to further monopolize control over customers. The corporation, under this theory, would be directing consumers who normally bought from independent merchants to Zappos, which is an Amazon subsidiary.

That regulation of who sells what happens through what is called the Buy Box, which is the piece of web real estate shown to consumers that lets them buy an item. The screenshot of the Buy Box is below. Consumers can pick which merchant they buy from, but as you can tell from the small text in the red box, they are very unlikely to do so. So winning the Buy Box determines whether you can sell through Amazon. Suddenly, the theory went, Amazon was automatically awarding the Buy Box to its own branded subsidiary for unknown business purposes.

I confirmed that Amazon had done this for Zappos with a number of different brands. I even saw a letter from a major product company telling its retailers that yes, indeed, Zappos now had the advantage on them through Amazon. Over the next week, product makers complained to Zappos about the situation. Their other third party channels were being destroyed, which meant the brands would become entirely dependent on Amazon/Zappos. The situation returned to normal, Zappos stopped immediately winning the Buy Box. But then a few days later, it flipped back; Zappos started getting its immense advantage again. Finally, in the middle of last week, it returned to the status quo of Zappos being one of many merchants that could win the Buy Box.

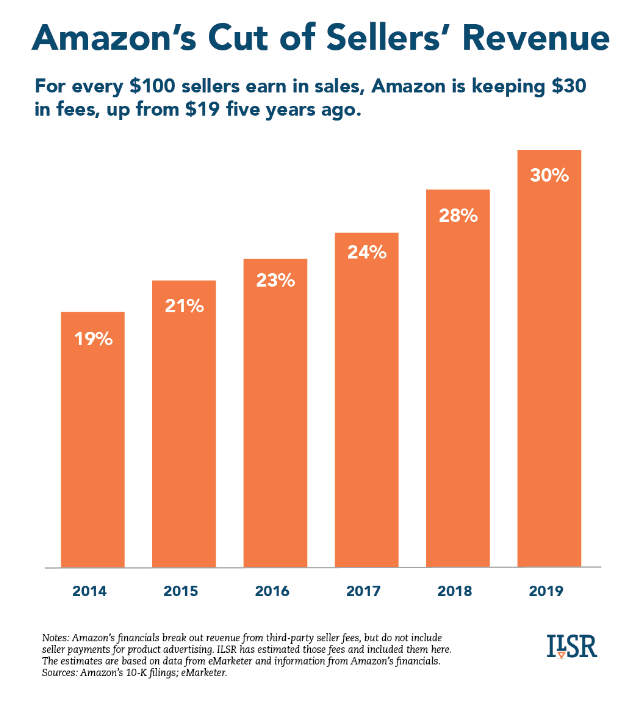

But something about the story didn’t quite make sense. There was no obvious reason for the changes, as Amazon benefits whether Zappos makes the sale or not. As the Institute for Local Self-Reliance just put out, Amazon makes a lot of money from third party merchants.

It also turns out there was a much larger set of algorithm changes beyond the specific line of business I was tracking. Thousands of merchants were suffering, and sellers were also trying to figure out whether the change in the Buy Box was a technical glitch or something more sinister. The truth was, no one knew, and Amazon was denying anything was wrong (which is their usual tactic, whether something was broken or not). Here are some of the cries from help from merchants whose businesses, and thus livelihoods, had suddenly fallen apart:

“I’m having the same issue. Called support and they just gave me the rundown of how my account is fine and that lots of factors control the buybox. Very scary.”

“I am also a victim of this Glitch since July 1st…Lost a lot of sale and buy box even though my rates are the lowest…Please help… I even tried to add my items to the cart to purchase but was not able to add them to my cart… I am desperate for the help.”

“Just because Amazon CAN help doesn’t mean they WILL.”

“Like many things on Amazon, stuff just breaks and no one ever tends to fix it. You can report these but you are just wasting your time as they will just heal randomly but no one from Amazon support will ever be able to actually resolve these issues and instead will just cut and paste random junk about buy boxes.”

There is now an entire media ecosystem and consulting world surrounding how to succeed on Amazon, replete with specialized software tools designed to win the Buy Box. One common piece of advice to deal with the recent Buy Box glitch was, “When Amazon sales plummet because of a glitch, one short-term solution is to lower your price by 1-2 percentage points to win the Buy Box. Then, as soon as you win it, raise the price. You won’t be able to do this manually, though. You need a real-time repricer like Sellery to stay ahead.” In other words, the way to deal with Amazon’s neglect is to buy consulting and software services.

In the end, I couldn’t figure out what was actually happening. Amazon’s secret algorithm toys with hundreds of thousands of businesses, with no recourse or transparency, and no active regulation even by Amazon itself.

This situation reflects the same absentee ownership dynamic on display in the counterfeiting ads enabled by Facebook and Google above. Amazon has control of the Marketplace structure, how consumers buy, and even the inventory of third parties, but it doesn’t have responsibility for any of it. Amazon gets paid whether it makes Zappos a dominant seller or whether it extracts fees from merchants for its warehousing and marketplace services, or whether its algorithm has glitches or not. It can’t be sued, because all merchants have to sign arbitration clauses in their contracts that prohibit lawsuits. Amazon is the government of online commerce, and who goes bankrupt based on Amazon’s arbitrary decisions is literally irrelevant to Bezos.

In 1986, Ronald Reagan made a famous joke about the coercive power of an incompetent and haphazard government over independent farmers, saying “The nine most terrifying words in the English language are, ‘I’m from the government and I’m here to help.’” Today, for merchants in America, Amazon is that government.

Congress versus $5 Trillion

These stories brings us to the big hearing tomorrow. After a year of investigating, the Antitrust Subcommittee now has the four CEOs up to testify at noon, men who in aggregate represent $5 trillion of market capitalization and the raw power over the channels of commerce that amount of money represents.

Congress has dealt with the power of monopolies. In 1950, Congressman Emanuel Celler, chair of that same Antitrust Subcommittee, wrote in Reader’s Digest on a threat made by General Electric in the refrigerator industry. A GE salesman had told a customer of a rival that GE would sell compressor’s “at any cost,” with the goal of killing off a competitor, the Tecumseh Company. GE CEO Charles Wilson, in testifying before Congress, was asked about this situation, to which Wilson admitted that, yes, a salesman had made such an offer, but not under orders. Wilson had talked to the President of Tecumsah to let him know that GE had no intention of destroying its rival. “I told him it was bunk,” said Wilson, “and that the salesman had been talked to.”

Celler wrote that, while it was good that GE had decided not to ruin its competition, the problem was the power it had to do so in the first place. “I don’t like to see men first terrorized,” Celler noted, “and then relieved to find that Charles Wilson is feeling kindly and won’t let his men shoot.” And that is the feeling that merchants have with Amazon, Facebook, Google, and Apple. They just hope that Jeff Bezos, Mark Zuckerberg, Sundar Pichai, Tim Cook or one of their underlings, are feeling kindly.

There are reasons to be wary of this hearing. As Dave Dayen noted, the format is such that each member of Congress gets only five minutes to grill all four CEOs, though members can stay for multiple rounds. These CEOs are going to be testifying remotely instead of in-person, which means they can be surrounded by lawyers who give them answers off screen. And while I had hoped for subpoenas for documents, it seems less likely that the Judiciary committee wants to fight to get such information. One of Facebook’s original investors, Roger McNamee, told CNBC that “This is at best the first step in a long process…Each one deserves a multi-day hearing.” He’s right, and I suspect there will be more hearings in future Congress’s.

Even so, just having these CEOs being forced to answer is a meaningful step forward. And some of the members genuinely understand the stakes. Here’s Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal, who pointed out that the problem of big tech is fundamentally political. “We need to move very quickly, as a Congress,” she said, “to reassert our authority into regulation of these tech companies and [their] anticompetitive practices.”

In America, the law is meant to protect us from arbitrary threats and the abuse of power in our commercial sector, in particular from monopolies and financial predators. It’s been a long time, over forty years, since policymakers even understood that their job was, in part, to regulate commerce so as to promote fair competition and the liberty that comes with it. As a result, others regulate our commerce, the most significant being Facebook, Google, Amazon, and Apple. But the tide is turning. These men will in the end have to answer for how they regulate, and the public, through Congress, will finally start getting a say.

Thanks for reading. Send me tips, stories I’ve missed, or comment by clicking on the title of this newsletter. And if you liked this issue of BIG, you can sign up here for more issues of BIG, a newsletter on how to restore fair commerce, innovation and democracy. If you really liked it, read my book, Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy.

* * *

P.S. A contact sent this note to me that I found interesting on Amazon/Whole Foods and cattle ranching.

I came across an Amazon scam yesterday that I’ll pass along for your files. I was talking to a farmer/rancher who lives up the road from me…she and her husband do mostly dairy, but they do some beef cattle too. She said slaughter houses are backed up by several months right now (COVID), so they haven’t been able to get their beef slaughtered. But, there’s a guy who buys 12-18 steer a month from them…she asked him what he does with them…he puts them in a pasture for a month and then sells them as “grass fed” (which rich suburbanites pay a premium for) to Whole Foods (who has front-of-the-line status at slaughter houses)…mind you, they feed these animals primarily grain (which is fine, but not what people think they’re buying) – only in the last month of their lives are they “grass fed”…and right now it works particularly well because Amazon can butt in line at the slaughter house. Fucking ridiculous…people pay primo $ for what is really just standard beef, and it gets to market easily while others wait.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/2EtkCyG Tyler Durden