Another Market Top Indicator: “Blank Check” IPO Issuance Explodes

Tyler Durden

Sun, 08/02/2020 – 19:55

The similarities with the housing bubble boom-bust are growing by the day. Not only are stocks at all time highs, to which we can now add record low yields and an all time high gold price as the 10Y real yield just dropped to an unprecedented minus 1% all time low…

… and risk-on euphoria is rampant among the retail investing community, but over the past year there has also been a veritable explosion of “blank check” companies which are shell companies that have no operations but plan to go public with the intention of acquiring or merging with a company with the proceeds of the SPAC’s initial public offering. Investment in SPACs usually surges near market peaks, when there is broad consensus among the professional investing community that equities are overvalued as there is now – as a reminder the June Fund Manager Survey from BofA found that a record 78% of Wall Street professionals believe that stocks are overvalued.

The last time we saw such a surge in SPACs? 2007.

And while the SPAC bubble burst in 2008 along with the rest of the housing/credit bubble, it has slowly recovered, and as Goldman’s David Kostin writes in his latest Weekly Kickstart, SPAC capital raising has soared YTD.

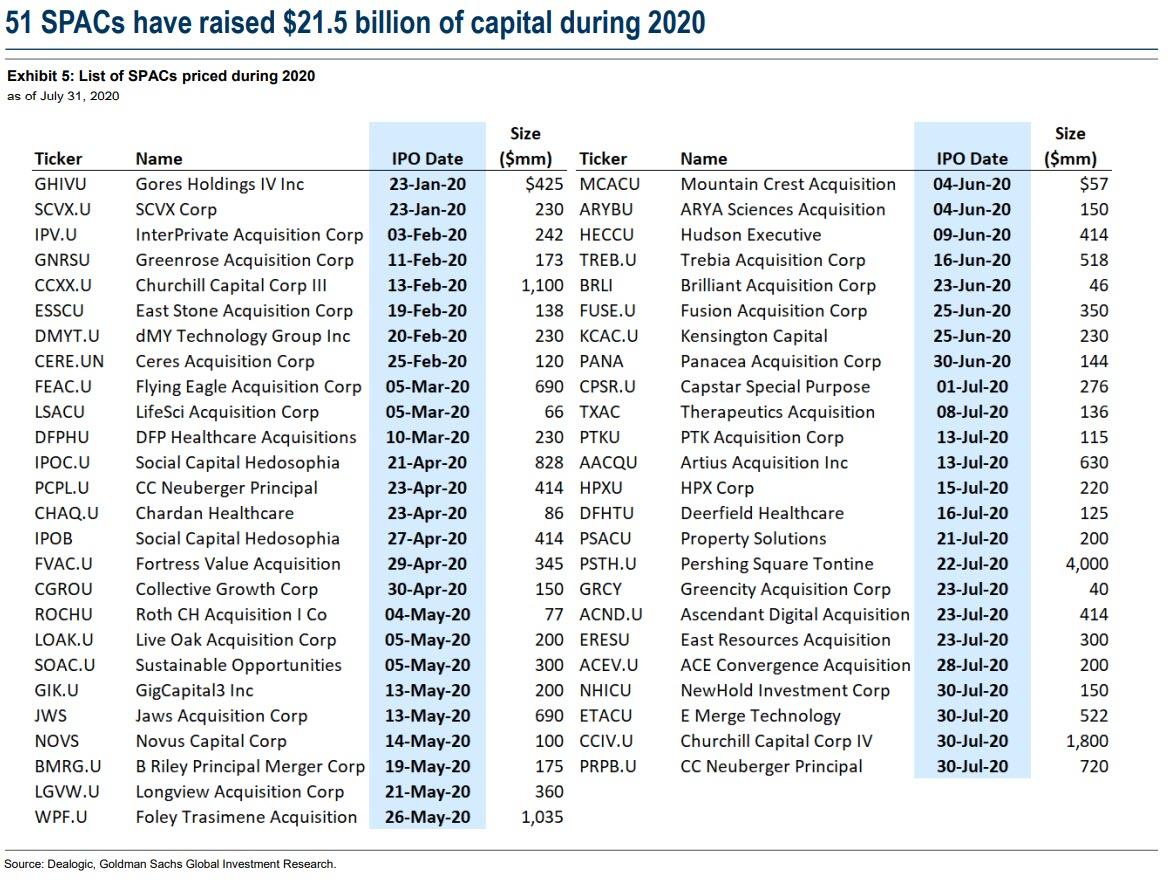

Some statistics: since the start of 2020, 51 SPAC offerings have been completed raising $21.5 billion, up 145% from the comparable year-ago period. In 2019, 51 SPAC IPOs were completed totaling $13.2 billion and 2018 witnessed 35 offerings for $9.3 billion. SPACs have accounted for one-third of all US IPO activity since the start of 2019.

As noted above, a SPAC is a “blank-check” company formed with the intention of acquiring or merging with another company. The SPAC needs to complete an acquisition within two years or the capital raised must be returned to investors, as such it mostly represents a vote of confidence in the sponsor or investor behind the SPAC and in their ability to find future deals that would generate a high ROI.

According to Goldman, completed SPAC offerings currently searching for acquisitions exceeds $38 billion. In a typical SPAC structure, the sponsor raises initial capital by issuing units consisting of 1 share and ½ or ⅓ of a warrant. The shares are generally priced at $10 and the warrants are typically struck 15% out of the money ($11.50) with a 5-year term and an $18 forced exercise.

And while by definition a SPAC is a blank-check, it comes with an embedded put option as Kostin explains:

Because the acquisition target is unknown at the time of the IPO, potential value creation is completely dependent on the ability of the sponsor to identify a target (typical private) company and negotiate the purchase. The SPAC purchase represents the de facto IPO for the acquired firm. However, in exchange for not knowing ahead of time the specific company that will be acquired, SPAC investors receive two benefits.

- First, the right to evaluate the pending purchase and elect to hold or redeem the initial investment at cost (plus accrued interest) two days before the vote.

- Second, warrants.

The decisions are separate. A SPAC investor may choose to retain both the shares and warrants, or redeem the shares and hold the warrants, or sell both.

The SPAC sponsor is typically compensated with a promote equal to 20% of pro forma equity and warrants. In a US SPAC, the sponsor’s promote is not contingent upon meeting any financial targets. However, the sponsors of some recent SPACs have put their equity promote into an earn-out that is only received if the company achieves certain performance objectives, further aligning the financial incentives of the SPAC sponsor and shareholders.

European SPACs are structured slightly differently. First, since they lack a redemption feature, they are truly “blank check” firms. The European SPAC investor owns the shares regardless of whether the investor likes the acquisition or not. Second, the sponsor does not receive a 20% promote up front. Instead, the sponsor only earns a promote if the company achieves certain return targets.

Once the IPO is complete, and the SPAC sponsor – now with millions in fresh funds in the bank – finds a suitable target, he or she negotiates a non-binding term sheet. Depending on the size of the transaction, the sponsor may wall cross potential new outside investors to raise a PIPE (private investment in public equity). The transaction is then announced to the public and an 8-K is filed.

Curiously, the SPAC investor base is highly fluid and as Goldman writes, many SPACs experience nearly a full rotation in their shareholder base during the time between the announcement of the deal and closing of the acquisition (transition from merger arbitrage traders and hedge funds to longer-term fundamental investors).

The sponsor will then file a proxy with the SEC, conduct a pre-merger roadshow, receive redemption notices (if any), and hold a shareholder vote. Redemption notices are due 2 days prior to the shareholder vote, and shareholders will typically determine whether or not to redeem based on where shares are trading at the time redemption notices are due. If the vote passes, the SPAC merges with the target company and will often undergo a ticker change to reflect the name of the target business.

On the other hand, if the vote fails, the sponsor will resume searching for a suitable target. After 24 months from the capital raise the SPAC will be closed and the capital returned to investors if a merger has not been completed.

So why the interest in SPACs?

As Goldman explains, from a capital raiser’s perspective SPACs offer companies a path to the public markets as an alternative to a traditional IPO. Two features of the SPAC process are notable: Forecasts and proceeds.

- First, in the traditional IPO process, issuers are prohibited from including any forward-looking guidance in their Form S-1 registration. As a result, prospective investors are required to evaluate the merits of an issue based on backward-looking results and their own expectations. In contrast, the SPAC due diligence process allows a target company to present forecasts and enhances the ability of a SPAC to acquire early-stage companies or those with complicated business models. This can be useful in businesses like sports betting, cannabis, electric vehicles, or other nascent industries that lack meaningful comparisons in the traditional IPO market. Of course, it is a given that the target company will present the most optimistic projections to potential investors, which is why removing the investor diligence aspect of the process is usually a sign of complacent groupthink whereby the investor base is willing to believe anything the target company presents similar to how i) rating agencies assessed all pre-crisis debt as stellar even if it was generally garbage and ii) investors are willing to engage in groupthink when someone else does their “diligence” job for them.

- Second, in a traditional IPO, the amount of new capital raised is limited, typically to 20%-25% of the value of a company. But in a SPAC transaction, no limit exists on potential proceeds. A SPAC may acquire a majority or minority interest in the target firm and the concurrent PIPE capital raise may be any size.

According to Goldman, whose taks is to spin SPACs as an attractive investment opportunity instead of yet another market top signal, investing in SPACs – from a portfolio manager’s perspective – “offers upside potential with downside protection.” And yes, ultimately, the upside potential is a function of the sponsor’s ability to identify the target, negotiate terms, inject needed external capital, and create long-term value. Which of course is also an admission by the provider of capital that they can’t find any other attractive investment opportunities and the money is bestowed upon someone who supposedly is good at finding the kinds of deals that have become especially scarce in the public markets. Meanwhile, the redemption option limits downside.

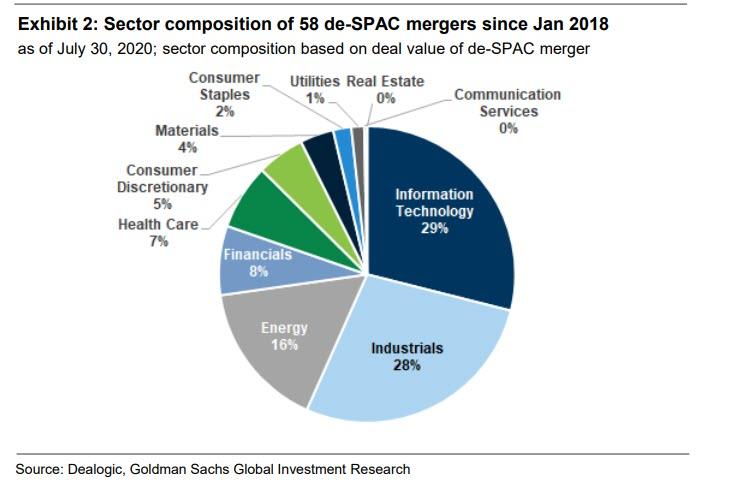

Some more statistics: Goldman analyzed 56 SPACs that completed mergers/de-SPAC transactions since January 2018. Tech and Industrials dominated the targets, followed by Energy and Financials.

The typical deal value was $920 million. During the 1-month and 3-month periods following the acquisition announcement, the average SPAC outperformed the S&P 500 by 1 percentage point and 11 %, respectively, and beat the Russell 2000 by 6% and 15%, respectively. That’s the good news.

Now the bad news: the average SPAC underperformed both indexes during the 3, 6, and 12-months after the merger completion.

As shown in the chart above, the performance distribution is extremely wide, with the 75th percentile SPAC outperforming the S&P 500 by 22% while the 25th percentile transaction lagged by 69%. The comparable returns vs. Russell 2000 were from +37% to -63 %.

In other words, just like with regular IPOs, SPAC returns are a coin-toss and since they tend to underperform the broader market several months after the merger and after the initial euphoria fades one may as well just buy the SPY, which unlike a SPAC, is now actively managed by the Fed whose mandate is to never allow another market drop again. It’s also another indicator that a market top has been reached, although while in the past this would be a signal to take profits at this time – when the Fed is actively managing equity risk and making any material declines virtually impossible – this time is not only different, but the recent explosion in SPACs issuance may simply be an indicator to add on even more risk, with the Fed’s blessing of course.

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3k5688n Tyler Durden