Here Is Everything We Know About A COVID-19 Vaccine

Tyler Durden

Fri, 09/04/2020 – 05:30

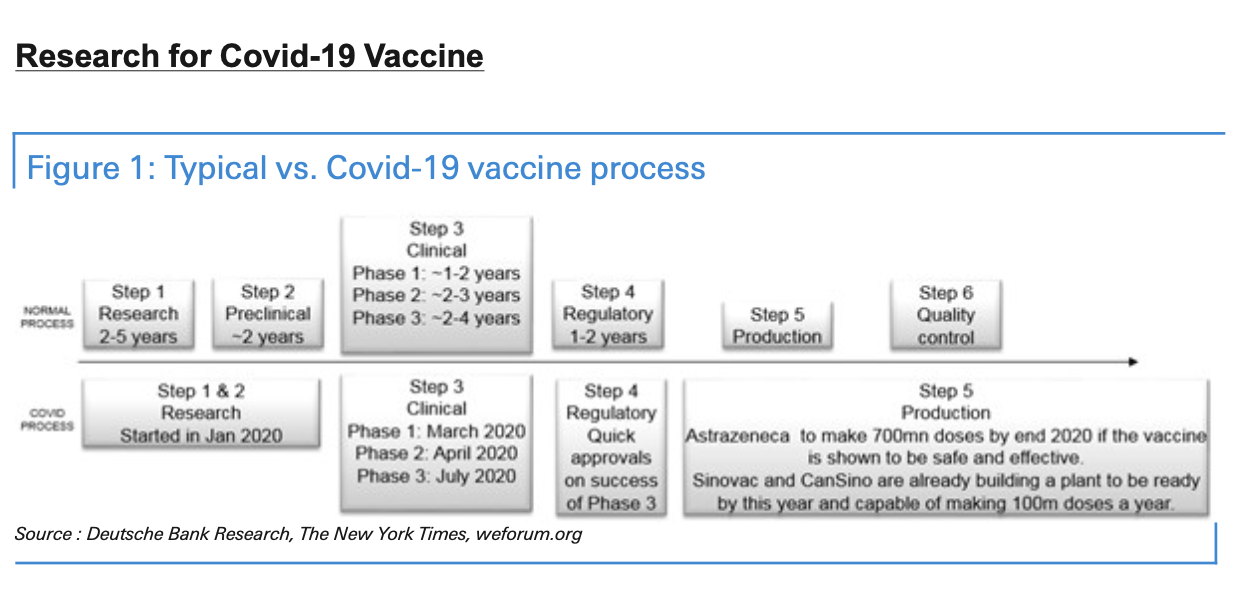

Under normal conditions, vaccines require as long as ten years of testing before they’re approved by regulators, then it takes some more time for drug companies to produce and distribute the product to millions of patients around the world.

Until very recently, the notion that the world could quickly develop and mass produce a vaccine for some new infectious disease within a matter of months seemed impossible.

Of course, these aren’t normal times. After unveiling the adenovirus-vector vaccine developed by the Gameleya Institute, Russian President Putin claimed that the vaccine was tested first on a small group of willing participants, including one of his own adult daughters. The implication was that traditional standards of medical ethics don’t always apply during extreme situations.

With vaccine news being the dominant story on Thursday, as investors around the world watched as the administration pushed the states to prepare to start distributing vaccine doses on an emergency basis come Nov. 1. Dr. Fauci later poured cold water on the administration’s enthusiasm, telling CNN that it’s unlikely a vaccine would be widely available before the end of the year. This, even after the CEO of Pfizer, which is partnering with German company BioNTech to produce what has become one of the leading vaccine candidates, claimed that the world will know whether their vaccine works in the coming weeks, as enrollment for its Phase 3 trials has nearly finished.

As Wall Street parses all of these competing claims, a team of analysts at Deutsche Bank has put together a lengthy “non-technical” overview of the quest for a vaccine to innoculate the world against SARS-CoV-2, before it simply burns through the global population.

Ultimately, the team concluded that while small quantities of various vaccines might become available on an emergency basis in November, it’s extremely unlikely that a vaccine will be approved and available for widespread use before Q12021.

The fact that more than a half dozen vaccine candidates have already made it to Phase 3 trials bodes well for the chances of a widely available workable vaccine in the coming months: After studying the processes for approval for vaccines developed to grant immunity to other infectious diseases, the researchers determined that while roughly one-third of vaccines make it past the first stage, once they make it to Phase 3, a whopping 85% of vaccine candidates will eventually be approved.

The report is replete with helpful charts that offer plenty of context for anyone who hasn’t been closely following along. More than 170 different vaccine projects are underway around the world, but a small handful of “elite” projects garner most of the attention from Wall Street and the press.

Aside from limitations related to supply chain, and the cooperation of regulators, DB pointed out that the perception that the FDA and government regulators are rushing the vaccine approval process has made a surprisingly large chunk of the population wary of vaccines, and forced vaccination programs.

Read the rest of the note below:

Vaccines normally require about 10 years of testing and additional time to produce at scale. Yet, many hope one will be available later this year. In this non-technical article, we provide a summary of Covid-19 vaccine developments. We present the status of research, possible timelines, and some potential obstacles ahead.

The good news is that, on average, once a vaccine for an infectious disease makes it to phase-three trials, it has an 85 per cent chance of being approved. As there are currently seven in phase-three trials, this implies six could be approved. However, we should caution that these are only the averages and no coronavirus vaccine has ever been tested or used at scale.

Yet, while a vaccine appears statistically likely, it is important to note that vaccines are not 100 per cent effective. In fact, most routine childhood vaccines are only effective for 85-95 per cent of recipients, according to the WHO. In addition, the US Centre for Disease Control says the ‘flu vaccine is regularly under 50 per cent effective. We delve into this in more detail.

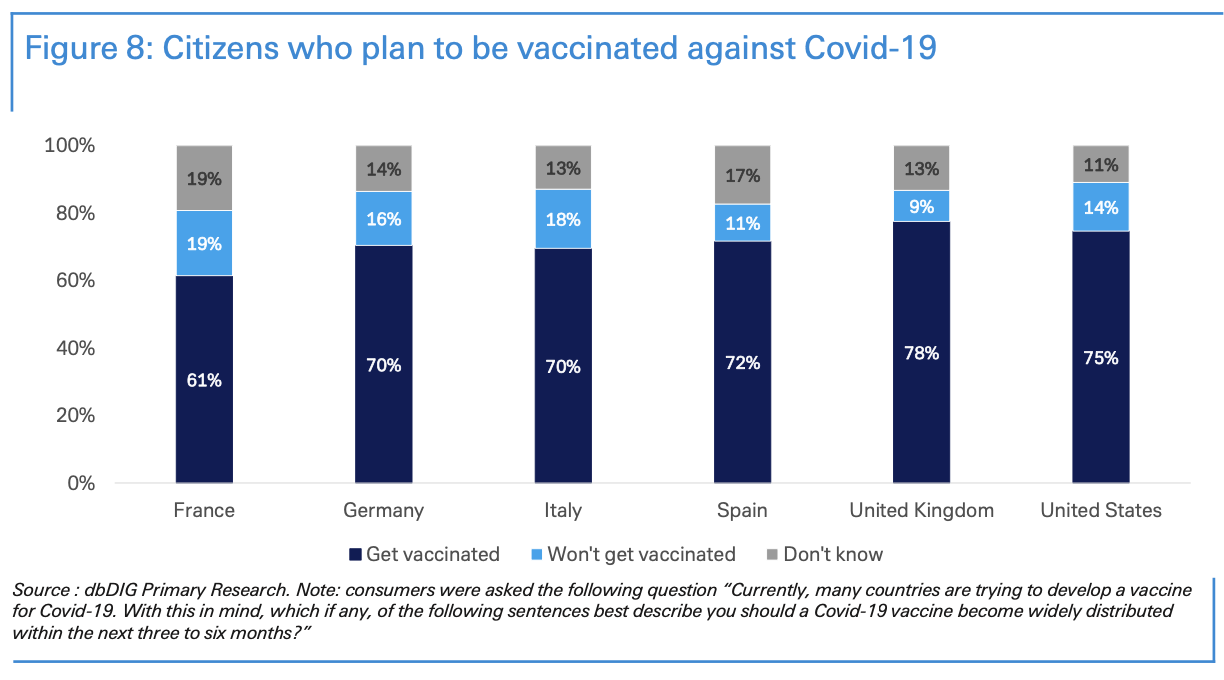

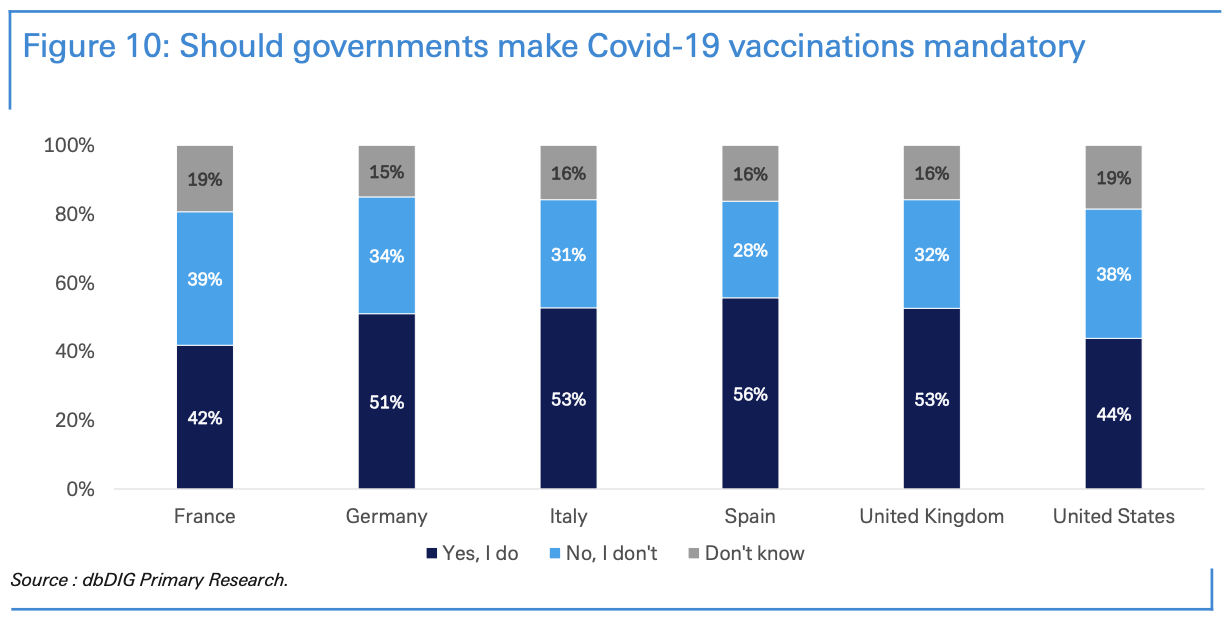

Finally, there is much debate about how many people will actually take the vaccine. Some argue that a quickly-developed vaccine cannot have been evaluated for long- term side effects. Furthermore, one survey notes that over three-quarters of Americans worry the vaccine approval process is being driven by politics. To counter this, some governments have discussed making a vaccine mandatory via various incentives and punishments. Of course, this presents a legal and ethical quagmire. Our proprietary survey shows that between 61 per cent and 78 per cent of people in various countries will choose to be vaccinated, however, there is strong disagreement on whether it should be mandated.

Looking forward, we should expect to hear significant developments soon. Most vaccines plan to be (if not already) available for emergency use this autumn so we will likely hear feedback on effectiveness within weeks. This could create a very interesting political dynamic ahead of the US election. A roll-out announcement may boost Mr Trump but any move is likely to be highly politicised which may impact its early success.

In total, more than 170 vaccine candidates were in development in August, and these efforts are being tracked by the World Health Organization. We provide an overview of the vaccine development process below.

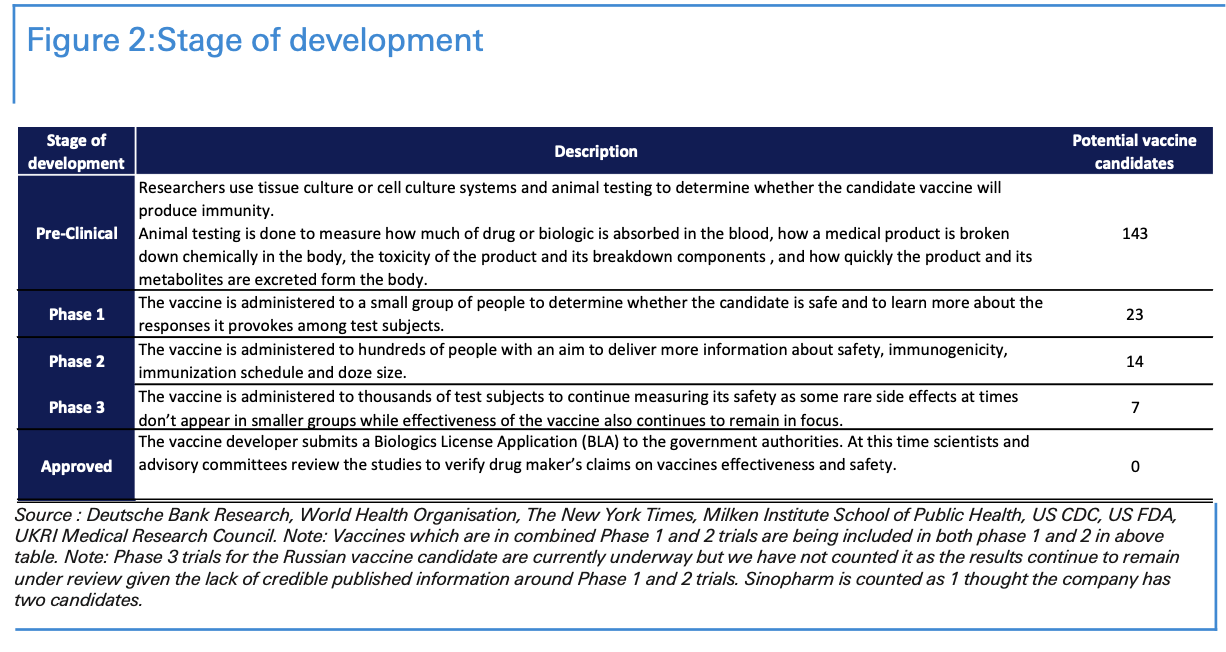

First, there is the pre-clinical phase, also called “phase 0.” In this phase, vaccines are not yet in human trials; rather, researchers give the vaccine to animals to see if it triggers an immune response. At the moment, there are 143 potential vaccines at this phase.

In phase 1, the vaccine is given to a small group of people to determine whether it is safe and to learn more about the immune response it provokes. At the moment, there are a further 23 potential vaccines at this stage or beyond.

In phase 2, the vaccine is moved into expanded safety trials and is given to hundreds of people. This further enables scientists to learn more about its safety and correct dosage. At the moment, there are 14 potential vaccines at this stage.

In phase 3, the vaccine is in large-scale efficacy trials and is given to thousands of people to confirm its safety, identify rare side effects, and measure effectiveness. These trials involve a control group, which receives a placebo. At the moment, there are 7 potential vaccines in this phase.

The last clinical stage is “approved,” which is granted to a vaccine after the sponsor applies to the relevant medical authority for use in the general population. At the moment, there are no vaccines in this phase. However, China’s vaccine candidate from CanSino Biologics has received limited approval for use by the Chinese military for a year from June 25 as a “specially needed drug”. Further, on August 11, Russia announced that its COVID-19 vaccine will be registered, in a step which is a precursor to mass vaccination. This makes it the first candidate to do so but there are concerns since the results of its Phase 1 and 2 trials were never published while phase 3 trials began only last week and as per media reports only 100 people were inoculated with the vaccine by early August.

Around 33% of vaccine candidates generally pass the clinical three phases to become a successful vaccine.

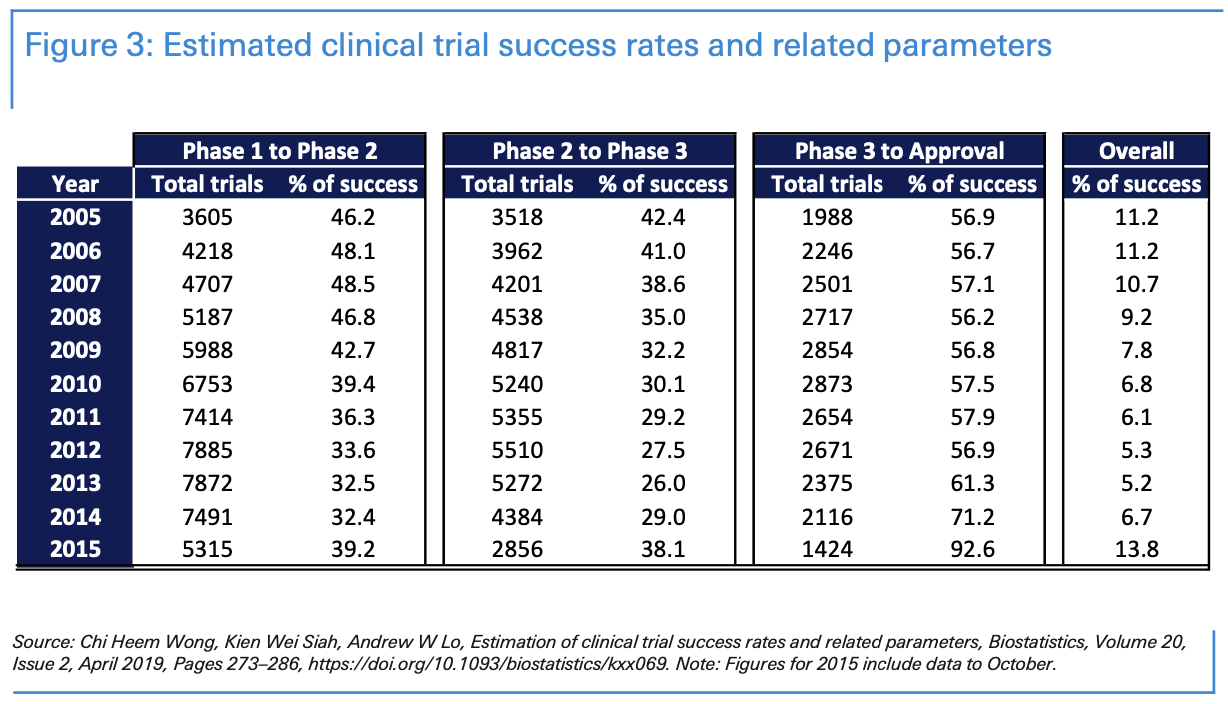

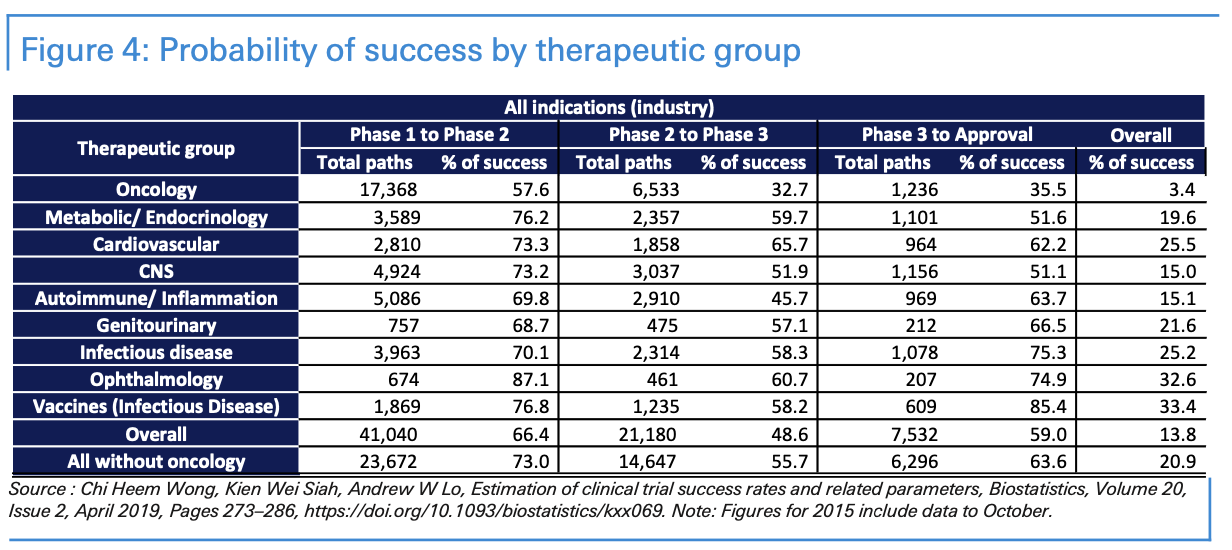

When considering the development process, it’s helpful to consider how long it takes for medications to be developed for other diseases. The percentage of drugs that successfully pass each stage of clinical trials remains low. Statistics vary significantly, depending on the sample, the illness, and the years. Approval rates range are usually higher in vaccines for infectious diseases and lower for investigational cancer treatments.

According to a study published in Biostatistics 1 published in 2019 using a sample of 406,038 entries of clinical trial data for over 21,143 compounds from 2000 to 2015, the probability of a medication’s success—to advance from phase 1 to approval—was 9 per cent on average from 2005 to 2015. Interestingly, 41 per cent of clinical trials navigate from phase 1 to phase 2 and 34 per cent from phase 2 to phase 3; more than 60% successfully reach approval after phase 3.

Approval rates in vaccines for infectious diseases were 33.4% overall over the 2000 to 2015 period. 77% of vaccines navigate from phase 1 to phase 2; 42% from phase 2 to phase 3; and 85% successfully reach approval after phase 3.

How effective are vaccines?

No vaccine is 100 per cent effective. According to the WHO, most routine childhood vaccines are effective to 85-95 per cent of recipients.

In addition, the US Centre for DiseaseControlsaysthe‘fluvaccineisregularlyunder50percenteffective.’2 Abig part of the problem is the extent to which a disease mutates. The seasonal flu is a good example of this as a new strain every year requires a new vaccine.

So far, there is various evidence that covid-19 has mutated; however, more research needs to be done here. It should be pointed out that mutation is not necessarily a bad thing. That is because over time, some diseases mutate into less aggressive strains. This allows that new strain to ‘live’ longer in its host. After all, if a virus kills its host too quickly, it will itself die out.

Vaccine production under supply-demand imbalance

Now that there are several vaccine candidates undergoing phase 3 trials, it seems more likely than it did six months ago that a vaccine will be developed at some point. However, with demand likely to far outweigh potential production capacity, the mass distribution of a vaccine will raise significant challenges.

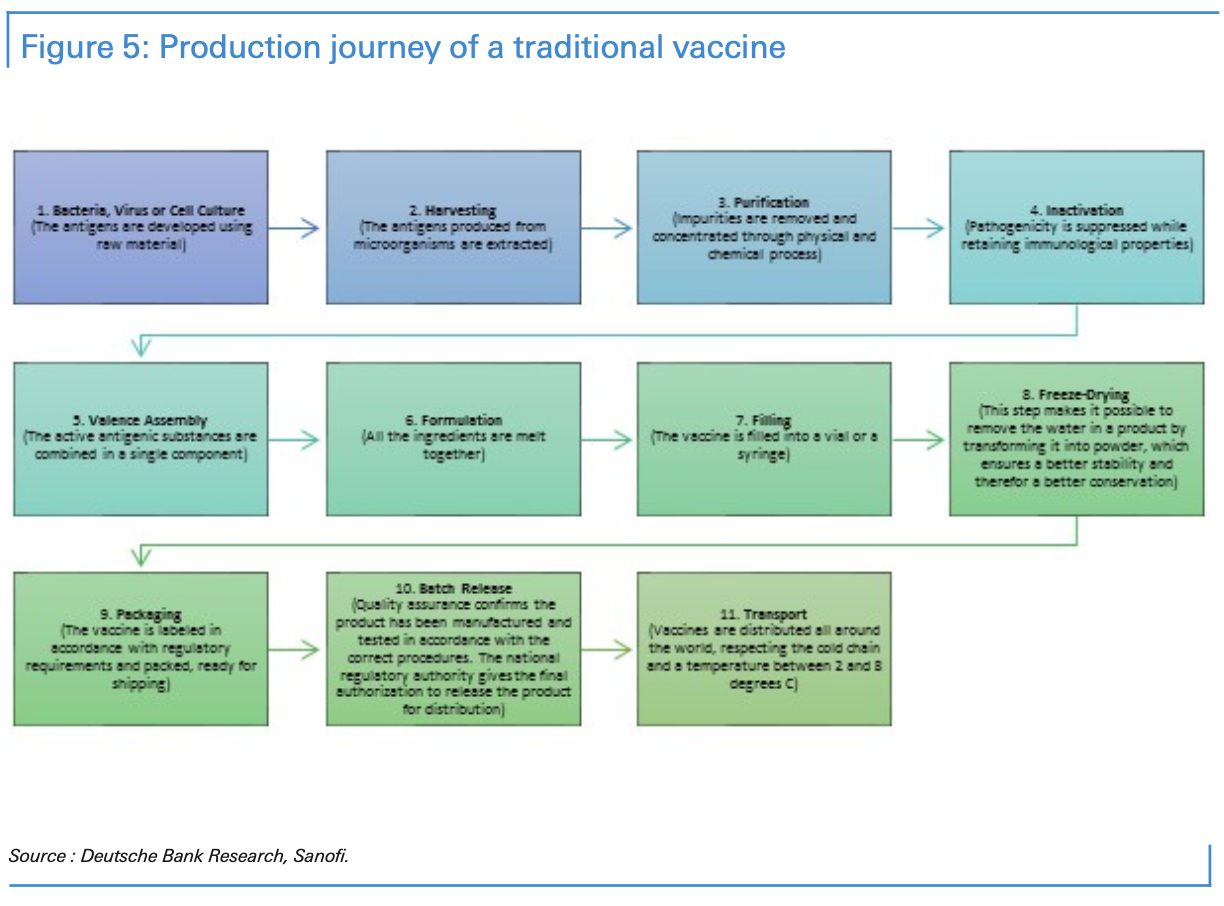

First, any rapid scale-up of global production will require technology transfer. That will involve the challenge of protecting intellectual property rights. Second is the difficulty of manufacturing and delivering vaccines, particularly given the need for vaccines to be kept within a certain temperature so they don’t lose their potency or efficiency. Vaccines must be transported internationally and locally through a series of temperature-controlled steps called the “cold chain.”

Some vaccines are easier than others to produce and scale-up. New types of vaccines, such as the “messenger RNA (mRNA),” if successful, are far easier to produce at a large scale. While a single five-litre bioreactor could produce as many as 50 million doses a year, traditional vaccines typically require 1,000-litre bioreactors to produce between 100 and 300 million doses.

Although no vaccines have been approved yet, countries and organizations are already investing millions in vaccine manufacturing. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has started building factories for seven of the most promising vaccine candidates. The US government has disbursed funds to manufacture potential vaccines from AstraZeneca, Moderna, Emergent BioSolutions, and Johnson & Johnson. China’s CanSino and Sinovac are building manufacturing plants to produce 100 to 200 million doses. Meanwhile, Serum Institute of India is under agreement with AstraZeneca to produce one billion vaccine doses if phase 3 trials are a success, with 400 million of those doses due by the end of 2020.

Today’s Frontrunners

China’s CanSino vaccine was the first candidate to reach phase 1 and phase 2. However, vaccine candidates Sinovac, Sinopharm, Astrazeneca, Moderna, CanSino, BioNTech/Pfizer and Murdoch Children’s Research Institute all reached phase 3 in July/early August. As we previously stated, reaching phase 3 does not necessarily lead to a successful vaccine, but it does indicate a high probability of success – on average 85% of new vaccines for infectious diseases successfully reach approval after reaching phase 3 trials.

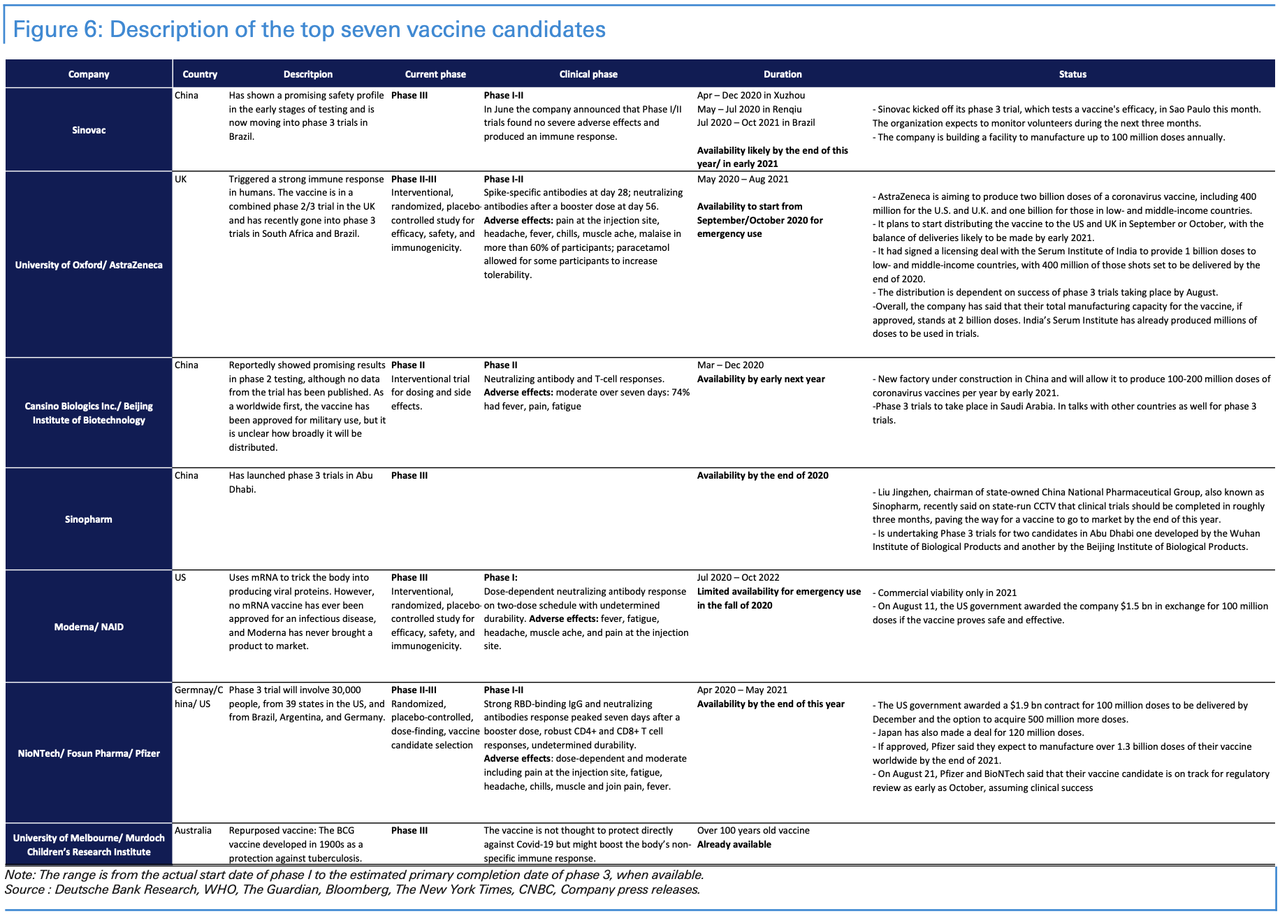

According to the World Health Organization, the top seven vaccine candidates, which are all in phase 3, are more likely to reach approval quickly. They are being submitted by the following organizations: Sinovac; University of Oxford/ AstraZeneca; CanSino Biologics Inc./Beijing Institute of Biotechnology; Sinopharm (Wuhan Institute of Biological Products/ Beijing Institute of Biological Products); Moderna/NIAID; BioNTech/Fosun Pharma/Pfizer and University of Melbourne/ Murdoch Children’s Research Institute.

We have summarized in the table below the description of each, their current clinical phase, the estimated primary completion date of phase 3 (when available), and what the organizations have communicated.

Vaccine development, expected timeline, and possible roadblocks

Research efforts began in January 2020 with the deciphering of the SARS-CoV-2 genome, and the first vaccine safety trials on humans then started in March. With organisation and rigorous work, we could see the development of an effective vaccine by early 2021. There’s also the prospect of progress even earlier than that, since researchers leading the Oxford University vaccine effort have said their vaccine could be ready for emergency use as soon as September 2020 if phase 3 trials are successful. This accelerated timeline has been possible due to a combination of important factors.

First, the emergency nature of the situation has led to a shortened testing timeline. All candidates have received regulatory approvals to move quickly to human trials, skipping years of animal trials that are normally required when developing vaccines. Related to this, some organisations have combined research phases to accelerate vaccine development. Some coronavirus vaccines are now in combined phase I/II trials.

Second, improvements in sequencing and advancements in bioengineering technologies have helped significantly. This has helped in developing a new type of vaccine called Messenger RNA (or mRNA for short), which give the body instructions to create disease specific antigens itself. Because of this, mRNA vaccines don’t need to be cultured in large quantities and then purified, and are much faster to produce as a result. Both Moderna and BioNTech have vaccine candidates that are based on mRNA.

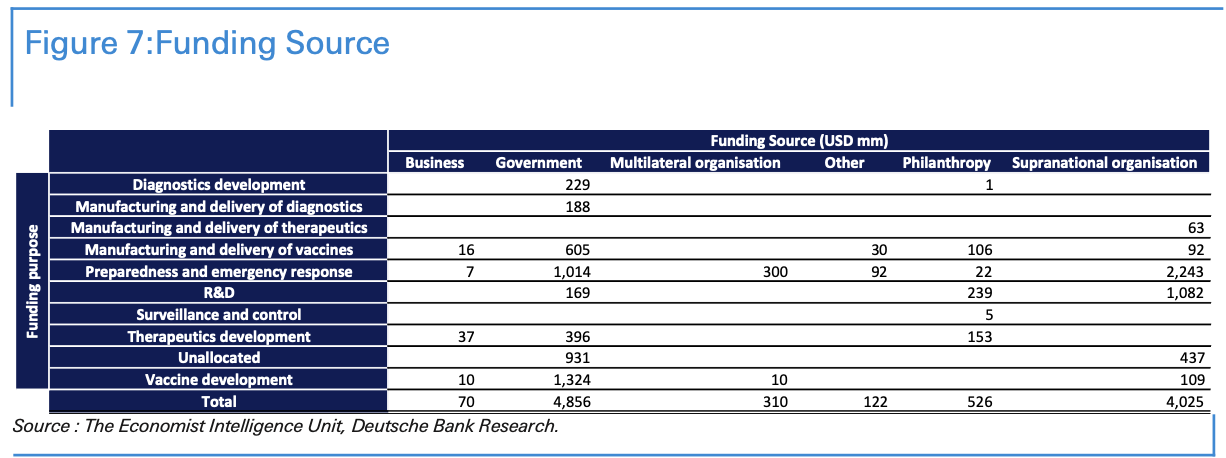

Third, national and international support and funding has fuelled research efforts. Various governments have announced different programs to financially aid the development of vaccines. We have summarized in the table below the funding source with their different purpose.

Finally, we have prior knowledge of coronaviruses. SARS and SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes Covid-19, are roughly 80 percent identical. Both use so-called spike proteins to grab onto a specific receptor found on cells in human lungs. So, using the existing research about SARS, scientists have been able to push ahead quickly.

Looking forward, we should expect to hear significant developments by November. Most vaccines plan to be (if not already) available for emergency use this fall so we will likely hear feedbacks on effectiveness. As an example, the UK’s Oxford vaccine aims to conclude phase-three trials by November. Ahead of national elections, particularly those in the US, a Covid-19 vaccine could play positively for the incumbants.

Why don’t we have a vaccine for SARS and MERS?

On the face of it, it is worrying that no one has ever tested or used a coronavirus vaccine at scale. Indeed, no general vaccine was developed after the SARS and MERS outbreaks experienced over the last 20 years. Despite this, there are some differences between covid-19 and these prior diseases that do not necessarily mean a vaccine for covid-19 will be materially more difficult to produce than other vaccines that are currently in wide circulation.

Ironically, the fact that the 2003 SARS outbreak was very acute hindered the chance

of a vaccine being developed. In other words, because SARS had severe symptoms that were unlikely to be missed during tracing, and because it did not transmit itself asymptomatically, authorities found it easier to control it.4 As such, the funding for several initial vaccine candidates was diverted elsewhere. Similarly, vaccine candidates to combat the 2012 MERS outbreak were hampered by the relatively lack of the disease after governments managed to control it. It is hard to test the efficacy and side effects of a vaccine on the general population if the disease is not widespread enough.

So, the lack of an approved vaccine for SARS and MERS should not necessarily be seen as a bad thing. Rather, it is largely reflective of the relatively-low incidence of the two diseases and the fact that vaccines can only be approved after widespread testing.

The big unknown is how many people will be willing to take a successful vaccine.

In some ways, the situation echoes the prisoner’s dilemma. Although most people believe that others should get vaccinated, many are not willing to be vaccinated themselves, something that would enable the virus to continue spreading.

Due to the speed at which vaccine are being developed, and the economic damage in the meantime, concern has been amplified. In particular, the political incentives for a vaccine have led many to worry that normal robust processes are being following. For instance, one survey notes that over three-quarters of Americans worry the vaccine approval process is being driven by politics. Given the presidential election is scheduled for November, if a vaccine is approved before then, it could help President Trump’s reelection pitch but risks becoming highly politicised.

We surveyed more than 5,500 citizens in France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the UK, and the US to test their intention of being vaccinated for Covid-19. Our dbDIG proprietary survey indicated that the majority of people surveyed were willing to be vaccinated.

In relation to Covid-19, most people surveyed plan to be vaccinated within the first six months after a vaccine is released. These numbers peaked in Anglo-Saxon countries, where 61% of British and 59% of Americans said they would be ready to be vaccinated within the first three months of the vaccine coming out.

An extreme scenario to ensure full vaccination coverage would be to mandate vaccinations. In our dbDIG proprietary survey, we asked people if they believed that governments should mandate Covid-19 vaccination. Among the Spanish, 56% believed that the national government should mandate vaccination, whereas only 42% French believed in mandated vaccinations.

Moving on to the final section of the note, DB features a breakdown of ‘Operation Warp Speed’, the Trump Administration plan to pick up the tab for drugmakers working on vaccines in the hopes of bringing them to market much more quickly.

The OWS has under taken below actions to support vaccine development efforts:

March 30: announced $456 mn in funds for Johnson & Johnson’s candidate vaccine.

April 16: made exit disclaimer icon up to $483 mn in support available for Moderna’s candidate vaccine, which received a fast-track designation from FDA.

May 21: announced up to $1.2 bn in support for AstraZeneca’s candidate vaccine, developed in conjunction with the University of Oxford. The agreement is to make available at least 300 mn doses of the vaccine for the US, with the first doses delivered as early as October 2020.

July 7: announced a $ 1.6bn funding for vaccine maker Novavax to expedite the development of its coronavirus vaccine. The deal would pay for Novavax to produce 100 million doses of its new vaccine by the beginning of next year — if the vaccine is shown to be effective in clinical trials.

July 22: announced a $1.9 bn contract for 100 million doses to be delivered by December 2020 with an option the option to acquire 500 million more doses.

July 31: announced c. $2 bn in support to Sanofi and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) to support advanced development including clinical trials and large- scale manufacturing of 100 million doses of a COVID-19 investigational adjuvanted vaccine. Also has an otpion to acquire up to 500 million additional doses.

August 5: announced $1 bn in funds to Johnson & Johnson in exchange for 100 million doses of vaccine with an option the option to acquire additional doses up to a quantity sufficient to vaccinate 300 million people.

August 11: announced an additional $1.5 bn in funds for Moderna’s vaccine candidate in exchange for 100 million doses if the vaccine proves safe and effective.

The OWS has under taken below actions to support vaccine manufacturing efforts:

On May 21, April 16, and March 30: HHS entered agreements with AstraZeneca, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson respectively include investments in manufacturing capabilities.

June 1: HHS announced a task order with Emergent BioSolutions to

advance domestic manufacturing capabilities and capacity for a potential COVID-19 vaccine as well as therapeutics, worth approximately $628 mn.

July 27: HHS announced a task order with Texas A&M University and FUJIFILM to advance domestic manufacturing capabilities and capacity for a potential COVID-19 vaccine, worth approximately $265 mn.

August 4: Grand River Aseptic Manufacturing Inc., (GRAM) Grand Rapids, Michigan, was awarded a $160 million firm-fixed-price contract for domestic aseptic fill and finish manufacturing capacity for critical vaccines and therapeutics in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

The OWS has under taken below actions to support vaccine distribution efforts:

May 12: announced a $138 mn contract with ApiJect for more than 100 million prefilled syringes for distribution across the US by the end of this year, as well as the development of manufacturing capacity for the ultimate production goal of over 500 million prefilled syringes in 2021.

June 9: announced an effort to increase domestic manufacturing capacity for vials that may be needed for vaccines and treatments:

$204 mn to Corning to expand the domestic manufacturing capacity to produce an additional 164 million Valor Glass vials each year if needed.

$143 mn to SiO2 Materials Science to ramp up capacity to produce the company’s glass-coated plastic container, which can be used for drugs and vaccines.

August 14: HHS and DoD announced that McKesson Corporation will be a central distributor of future COVID-19 vaccines and related supplies needed to administer the pandemic vaccinations.

* * *

Source: Deutsche Bank

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3boAbnJ Tyler Durden