The Next Normal: Is Central-Bankism Transitioning To Fascism

Tyler Durden

Sat, 09/05/2020 – 18:50

By Michael Every of Rabobank

The Next Normal: What it “-ism” and what it “-ism’t”

“Normality is the Great Neurosis of civilization.” – Tom Robbins, author

Summary:

- We are now moving from the “New Normal” into the realm of “The Next Normal”: can we define what our new architecture will look like?

- To do so, we look beyond economics to the historical “-isms” of political-economy

- We believe we live under capitalism: do we, as fiscal and monetary Rubicons are crossed?

- Or are we already heading for central-bankism, a post-capitalism with echoes of feudalism?

- Marxism claims it is still alive: but it looks much more central-bank capitalism

- There are unhappy parallels between aspects of our emergent political-economy and fascism

- US-China tensions are about mercantilism, but still matter for that

- We need a new political-economy in the “Next Normal”, but none provide a solution for our global trilemma, which suggests some forms of schism are inevitable

- Indeed, expect more populism, underlining why we need a political-economy ‘guide rail’

- Volatility looms as populist political-economy will naturally demand internal and external “reallocation”

The “Next Normal”

In late 2019 we published a report titled “A Decade of… What Exactly?” which underlined how disappointing the economic erformance in the post-global financial crisis “New Normal’ era had been on almost all fronts.

It showed how the experience had been one of: lower GDP growth, lower inflation, lower wage growth, and lower productivity alongside higher inequality, higher debt, higher asset prices, high and rising political populism, and high and rising geopolitical tensions, particularly between the US and China. All of these were issues we had been flagging for years.

We concluded that the outlook for the decade of the 2020s was deeply worrying.

We had likewise already recognised earlier in the year that the socio-economic impact of Covid-19 is likely to be severe and broad-ranging enough. Indeed, so much so that the concept of “The New Normal” is already behind us; we are now moving into the realm of “The Next Normal”.

This report will look at what this is likely to mean structurally – can we define what our new architecture will look like?

In order to look at overarching structures one needs overarching definitions: and in order to deal with such definitions one needs to deal with political-economy.

This is understandably not something the market wants to pay attention to – for reasons we will explain. Markets and economists would much rather be talking about monthly ISM surveys than the world of “-isms”.

Of course, such key US data are important – but they are cyclical at a time when it is crucial to understand the structural trend.

Not doing so means we don’t understand the foundations we are building on, or how solid –or not– they are. It is, at best, to ignore the long-run for the short-run and, at worst, to mistake signal for noise.

Indeed, we will try to show that “-isms” have major implications for markets; especially given most current markets have been driven to record highs by very ‘wet’ central-bank liquidity. We may like to think that development itself isn’t an “-ism”, but it very much is!

“Markets weed out inefficient practices, but only when no one has sufficient power to manipulate them.” – Ha-Joon Chang, economist

Whatabout “-ism”

So what is political-economy? As a discipline, it originated from moral philosophy, which contemplates what is right and wrong and how people should live their lives. In the 18th century this branched off to ideas related to the administration of states’ wealth. ‘Political-economy’ grew to study production and trade and their relations with laws, customs and government, and with the distribution of national income and wealth (the moral component). It argues politics and economics are fundamentally inseparable and the relationships between states and markets is required to understand how our world works.

The history of economic thought is, without question, that of political-economy. The classical economists –Smith, Malthus, Ricardo, and of course Marx– all saw themselves as writing about political-economy, and Smith moral philosophy, not about “economics”. So did later thinkers like Schumpeter.1 Economics as a standalone ‘science’ only emerged after the 1930s.

Political-economy is rarely taught as part of economics. The majority of economists’ professional schooling and careers never touch on it: economics is here, politics is there prevails, which is why discussing political-economy is avoided – even though that view is itself political-economy!

However, ready or not (and it is mostly not), willingly or unwillingly (and it is mostly unwilling), and openly or tacitly (and it is increasingly openly), political-economy is set to make a come-back. As one example, consider this recent research paper by two Fed economists, “Market Power, Inequality, and Financial Instability”. Its abstract argues:

“Over the last four decades, the US economy has experienced a few secular trends, each of which may be considered undesirable in some aspects: declining labor share; rising profit share; rising income and wealth inequalities; and rising household sector leverage, and associated financial instability. We develop a real business cycle model and show that the rise of market power of the firms in both product and labor markets over the last four decades can generate all of these secular trends. We derive macroprudential policy implications for financial stability.”

Consider that firm power relative to that of labour is pure political-economy – and also represents structural economic arguments we have been making for years that explains why we were stuck in a “New Normal”.

Indeed, some in the economics establishment understand that they need to broaden their approach – they just generally only say so after leaving office rather than in it. For example, former Bank of England (BOE) governor Mervyn King gave a speech in 2019 bewailing global “secular stagnation” and the lack of intellectual progress towards solving this problem. King argued:

“…to escape permanently from a low growth trap involves a reallocation of resources from one component of demand to another, from one sector to another, and from one firm to another… The answer goes well beyond monetary and fiscal policies to include exchange rates, supply-side reforms, and measures to correct unsustainable national saving rates.”

Crucially, moving beyond an ‘economic’ modulation of fiscal and monetary policy towards a reallocation of resources is political-economy. Who gains? Who loses? How much? With what moral justification and political support or opposition?

This therefore moves economics back into the uncomfortable world of “-isms”, which needs lots of new thinking. Indeed, King noted:

“Following the Great Depression, there was a period of intellectual and political upheaval. No-one can doubt that we are once more living through a period of political turmoil. But there has been no comparable questioning of the basic ideas underpinning economic policy. That needs to change.”

King is correct. The 1930s saw ‘economics’ branch off from politics. Free-market policies had helped to create the catastrophic conditions of the 1930s and so held little popular appeal; the logical ‘political’ step for those favoring free-markets was to present economics as a ‘neutral’ ‘science’, like physics, with equally complex maths.

Meanwhile, the parallel developments were very much into the realms of political-economy: Keynesianism (and the real thing, not the erroneous, milquetoast version that was “synthesized” back into the mainstream ‘science” of neoclassical economics after WW2); communism on the far left; and fascism on the far right. It might be hard to believe today, but both of the latter were regarded as valid intellectual –and popular– rivals to capitalism at the time.

It is hard to avoid noticing that “socialism”, “Marxism”, “nationalism”, and “fascism” are all appearing with greater frequency in our political discourse again: but are we seeing any real revolutions in our political-economic thinking?

“I’m just opposed to a pure inflation-only mandate in which the only thing a central bank cares about is inflation and not employment.” – Janet Yellen, former Fed Chair

Solipsism

Arguably, no…and yes, and let’s start with the ‘No’. Development economist Branko Milanovic’s recent book “Capitalism, Alone” argues it is now the dominant global ideology having decisively won the battle of ideas. Ebullient stock markets are at record highs, credit spreads and volatility at lows, and capitalism does not look to be under any cyclical, let alone structural threat.

However, we also need to consider the ‘Yes’ side. The Covid crisis has seen a plunge in economic activity. Unemployment, bankruptcy, homelessness, and the collapse of entire economic sectors are still very real threats – and yet have coincided with stocks setting record highs. This was only because the crisis has already triggered some revolutionary responses:

- Interest rates have been slashed to record lows globally and negative rates are being discussed in several markets;

- Quantitative Easing has been massively expanded, in regards to the range of assets that can be bought, and in terms of how many countries have embraced it;

- Yield Curve Control is being openly used in some markets, and contemplated in others;

- Outright debt monetisation is happening;

- Fiscal deficits are approaching those in the peak years of WW2 due to support schemes for most sectors; and

- There seems no likelihood of this being reversed, with the risk they will actually be expanded.

The cumulative impact of these policies is so large as to bring into question the extent to which this is still a capitalist system. This is not hyperbole.

To explain that, let’s define capitalism – something that we rarely have to do because it is taken as so ubiquitous:

An economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include private property and the recognition of property rights, capital accumulation, wage labour, voluntary exchange, a price system, and competitive markets.

Of course, there are different schools of capitalism, e.g., the laissez-faire Anglo-Saxon, more interventionist Europe and Japan, and the Chinese model. While all retain private ownership of the means of production and profits, they also allow for variation in public ownership and regulation.

Moreover, capitalism can change substantially. From 1933 until the collapse of Bretton Woods in 1971, capitalism was highly regulated to solve the political-economy issue of “reallocation”: in the labour markets (regulation), the goods markets (tariffs), and in the capital markets (capital controls, limits on interest rates, and fixed exchange rates). From the 1970’s onwards, however, there was a global switch to financialised neoliberal capitalism.

First the global financial crisis, then Covid-19 have come crashing down on that paradigm. Is it still capitalism when the government is paying up to 80% of the salaries of the private-sector workforce not to work? When governments are running fiscal deficits of 15-20% of GDP, financed by the central bank? When central banks are buying junk-rated assets and the market is suggesting a shift to buying equities is possible? When central banks have de facto asset price targets? When governments are backstopping bank loans, and using tax incentives and tariffs to try to onshore supply chains? And when there is no indication how these policies can be reversed? (Indeed, how can they be without a disastrous socio-economic crash?)

All of these are valid questions. However, they are not being asked in the appropriate places. Instead, these staggering fiscal, monetary, and fiscal-monetary policy responses are sold as ad hoc, technocratic, and counter-cyclical, to be wound back once we ‘return to normal’. As such, the thorny issue of the political-economy remains ostensibly untouched. We say ostensibly because without doubt everything has actually changed.

The one exception, of course, is that of Modern Monetary Theory (which we covered in detail recently here). For now this political-economy framework remains on the fringes of policy discussions… yet central-bank actions such as debt monetisation are already de facto adopting it. This speaks to the broader issue here: radical steps are being taken by establishment economists, but with no recognition of the need to justify them under the umbrella of political-economy.

This is problematic for many reasons. Among them is that to open the doors to such radicalism without the ‘guide rail’ of an “-ism” also leaves the door open to worrying future scenarios, as with the introduction of a new technology without a legal, regulatory, or moral framework within which it can operate. (Though, conversely, starting with a rigid orthodoxy such as neoliberalism or communism, and shoehorning reality into it has not worked well in the past either.) On which note, we need to look at “-isms” again.

“The difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from the old ones.” John Maynard Keynes, Economist

Post-Capitalism

Speaking of “-isms”, before capitalism the world had feudalism, defined here as:

“Legal, economic, military and cultural customs structuring society around holding land in exchange for labour. The nobility held lands from the Crown in exchange for military service, vassals were tenants of nobles, and peasants were obliged to live on vassal’s land and give labour and a share of their produce.”

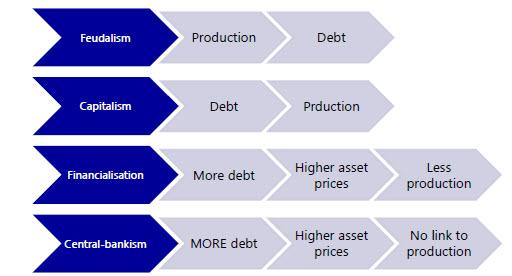

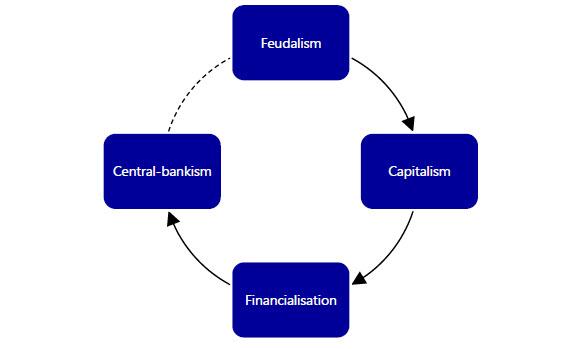

The feudal political-economy was simple. Peasants grew food and handed much of this over to their lord, who did the same to his lord, and so on up to the Crown. On the basis of this crop, monarchs were able to borrow from money-lenders. The chain was production > debt.

Under capitalism, this was reversed. Banks make loans to capitalists, who invest the funds in capital stock, produce goods, and repay the loans with the profits. The chain is debt > production.

This advance, alongside the industrial revolution, explains why growth boomed under capitalism while it had stagnated under feudalism.

However, with financialisation we get more debt (and higher asset prices) and yet less physical production as investment flows into financial assets and not productive capital stock (and so onwards in wages). Political-economy has been pointing this out for over a century: economics still does not understand it.

Under capitalism with a massively active central bank –“central-bankism”– the process is taken to its extreme. We get soaring debt and soaring asset prices that are almost divorced from actual production or investment: look at the divergent trends in stocks and GDP in Q2, for example. That said, markets and the real economy are very different animals2, which is part of the broader point that is being made: all the focus is on one when ‘life is elsewhere’.

This has even been referred to as “post-capitalism” – perhaps a fitting title in an era when some of the most valued stocks are no longer ones that offer their own product or content, just other people’s.

What central-bankism arguably shares with its distant ancestor of feudalism is an extractive, asset-based focus, and that those at the very top get very rich while those at the bottom of the pyramid get the opposite outcome. In both absolute terms the political-economy of this system is indeed one of reallocation – upwards.

Yet we are continuously told that central banks are pushing trillions of USD into the financial system, sending asset prices skyrocketing, to help those at the bottom of the socio-economic pyramid!

How is this state of affairs going to be sold to the public going forwards, especially in the absence of any over-arching political economy as justification? It surely can’t be dressed up behind the fig leaf of economic ‘science’ forever.

How can the logic of “We have to push up house and stock prices to keep workers in jobs” compete with “Why not use that money to employ workers and let asset prices do what they will?” After all, if we are to abandon parts of the definition of capitalism in “voluntary exchange, a price system, and competitive markets” in some assets, why in some and not in others?

In short, we can expect vigorous political-economy discussions about “reallocation” to erupt going forwards; and the weaker the “Next Normal” growth proves to be, the more and the faster this will happen.

In the near term, therefore, we have concerns over general deflation alongside asset-price inflation where central-bankism flows. In the medium term, however, a broader inflation would threaten – and with no institutional framework capable of reeling it in.

“Catch a man a fish, and you can sell it to him. Teach a man to fish, and you ruin a wonderful business opportunity.” – Karl Marx, philosopher

Marxism?

If capitalism has severe looming challenges from within –again– does it also really not have any from without? Milanovic obviously says no, but is that true?

Consider US Secretary of State Pompeo’s constant attacks on “Chinese communism”, for example, and his claims that China is a “threat” to Western economies and their “liberty”. That sounds ideological. Moreover, in August Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party Xi Jinping explicitly stated:

The foundation of China’s political economy can only be a Marxist political-economy, and not be based on other economic theories… The dominant position of public ownership cannot be shaken, and the leading role of the state-owned economy cannot be shaken.

That also sounds ideological: but here we need to dive into “-isms” again to define Marxism:

The political, economic, and social principles and policies advocated by Marx, especially: a theory and practice of socialism including the labour theory of value, dialectical materialism, the class struggle, and dictatorship of the proletariat until the establishment of a classless society.

The classless society end-goal above was defined by Marx as communism, the definition of which is:

A theory or system of social organization in which all property is owned by the community and each person contributes and receives according to their ability and needs.

Does that sound like the contemporary Chinese political economy with its middle class hundreds of millions strong, and its rising stock and housing markets? Indeed, doesn’t the Chinese state allow property rights, capital accumulation, wage labor, voluntary exchange, a price system, and competitive markets? (Or at least as much as the “capitalist” West does?)

As such, isn’t Milanovic right that China, for all its differences, still sits closer to capitalism than communism in this binary choice of political-economy? If so, surely Western capitalism is not under any kind of threat from China?

Certainly, China’s economy does not look like communism at all in one key regard: there are no chronic shortages, which plagued the former Soviet bloc. It looks very consumerist and Western – which is why Western firms have been happy doing business there.

However, there is instead massive over-supply in many areas, which a true market system would resolve via bankruptcy and write-offs/write-downs. Again, however, this is no longer an area where the West can preach given the marked shift towards ever-greater “zombification” of the economy under central-bankism, as functionally bankrupt firms continue to survive thanks to low interest rates, bailouts, and profits from financial speculation, not their core business.3

Of course, China also has massive over-investment in gargantuan state megaprojects, which have an increasingly Soviet feel. Indeed, its state sector also plays a large role in the “commanding heights” of the economy, which is linked to the general over-production problem. It seems hard to imagine that this will not emerge as an issue in the West if central-bankism continues: can all the capital really be ploughed into houses or shares, and not into national champions or infrastructure or new technologies that need vast scale?

Again, if it is a purely binary choice then China is still “capitalist” – and central-bankism looks increasingly like Chinese capitalism

However, but that does not mean that there is no underlying cause for US and Western grievances with China’s economic model. In short, tensions stem from yet another “-ism”: mercantilism. A clear definition of this is:

The economic theory that trade generates wealth and is stimulated by the accumulation of profitable balances, which a government should encourage by means of protectionism.

China is mercantilist in that for it trade is political and always aimed at a surplus as high up the value chain as possible. As we covered extensively in “The Great Game of Global Trade”, a mercantilist approach will always generate a backlash from a free-trade partner eventually, and that’s true even if both countries are nominally capitalist.

Obviously, mercantilism is in opposition to free trade, which, oddly, has sat largely untouched as part of our new central-bankism so far. However, as the discussion turns to political-economy the attractions of mercantilism –as national security, or to “bring jobs home”– will grow. Here lies the potential for real problems.

“Fascism is capitalism plus murder.” – Upton Sinclair, writer

XXXX-ism

Time for another “-ism” then. Consider this political-economy definition:

XXXX-ism was seen as the happy medium between boom-and-bust-prone liberal capitalism, with its alleged class conflict, wasteful competition, and profit-oriented egoism, and revolutionary Marxism, with its violent and socially divisive persecution of the bourgeoisie….

Where socialism sought totalitarian control of a society’s economic processes through direct state operation of the means of production, XXXX-ism sought that control indirectly, through domination of nominally private owners. Where socialism nationalized property explicitly, XXXX-ism did so implicitly, by requiring owners to use their property in the “national interest”—that is, as the autocratic authority conceived it.

Where socialism abolished all market relations outright, XXXX-ism left the appearance of market relations while planning all economic activities. Where socialism abolished money and prices, XXXX-ism controlled the monetary system and set all prices and wages politically. In doing all this, XXXX-ism denatured the marketplace.

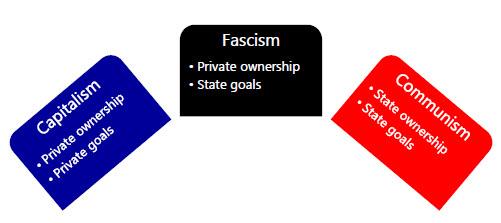

Can you define the missing term? The answer is fascism. (NB The above description from Seth Richman: there is no precise definition of ‘fascist economy’.) It was developed by Mussolini in the 1920s as a corporatist system to resolve class conflict through collaboration between the classes: a political-economy “reallocation” resolving top vs. bottom by turning it into us vs. them (and Mussolini on top).

Let us be abundantly clear: we are NOT saying China or countries who will embrace a more active central-bankism are fascist. However, it is a matter of historical record that fascist economies used the power of their private sector to achieve state-defined “national goals”.

Very broadly, capitalism is private ownership of the means of production for private goals; communism is state ownership of the means of production for state goals; and fascism is the private ownership of the means of production for “state goals”.

Market mechanisms play a key role in China, but operate with over-arching “state goals”. Under central-bankism, won’t we see the same happen elsewhere?

Can all that liquidity be on a free-market basis? Won’t the government want it to make the country great again, or level it up, or to build infrastructure or national champions, or a green, fusion-powered future, etc.? These are not necessarily bad state goals, just as they aren’t in China.4

Of course, fascist economies had other elements to flag:

1) Fascism discouraged entrepreneurship; today all encourage it. However, globally SMEs find life hard, and this seems unlikely to change in the “Next Normal”.

2) Fascist economies were autarchic; today the West and China are trading nations. Yet protectionism is clearly growing again in many places to help achieve state goals, as is talk of reciprocity on trade. Self-reliance was also China’s philosophy from 1949-1979 before opening its doors. Since the start of the trade war Xi Jinping has repeatedly called for self-reliance, and a new catchphrase known as ‘dual circulation theory’ is now being flagged. As the press noted in a recent article:

Xi has frequently mentioned that China needs to prepare for a new global situation where “unprecedented changes are taking place which have not been seen in the past 100 years”…Chinese leaders have called on the public to have a mentality of “fighting a protracted war”…It is in this context that the Chinese leadership has decided to push for an economic pivot by reducing its reliance on global trade and focusing on rebuilding supply chains and boosting the domestic economy for sustainable growth.

3) Fascism’s state goals were expansionism and imperialism; and there are accusations of such activities across several contemporary geopolitical flashpoints. Rapid rearmament in tandem is also hard to ignore – always a state goal par excellence, of course.

In conclusion, there are no contemporary fascist economies, but central-bankism could begin to inadvertently echo some of its features – with the best of intentions. This underlines the importance of having a political-economy ‘guide rail’: we need to set institutional, political, and moral boundaries for how it will operate.

“Schisms do not originate in a love of truth, which is a source of courtesy and gentleness, but rather in an inordinate desire for supremacy.” – Baruch Spinoza, philosopher

Schism

Yet here comes the biggest problem. We need a political-economy to guide us out of the “Next Normal” – but which one? Consider that the troika of problems that need to be addressed simultaneously are:

- To resolve (“reallocation”) the gaps between winners and losers within an economy, while retaining incentives and rewards and overall growth – or to justify why wealth and income gaps exist to the majority of the population;

- To resolve (“reallocation”) the gaps between winning and losing countries, that is to say between net exporters and unwilling net importers, or mercantilists and free-traders – or to be able to sell the position to the majority of the population; and

- To resolve both of the above AND maintain global cooperation on issues like climate change and population migration – or to sell the majority of the population on not worrying about them so much.

How can this be done? Indeed, can this be done? Arguably not. Let’s take the key example of the US, but the same logic applies to all countries.

On the first issue, prior to 2016 the political-economy narrative explained people were poor because they made bad choices and were rich because they worked hard. Politically, this is now a harder and harder sell.

On the second issue, the narrative was that free trade was always a good idea and “inevitable”, regardless of the negative economic outcomes in former manufacturing areas, the matching rise in income and wealth inequality, and the shift in relative power between the US and China. Politically, this is also now a much harder sell.

On the third issue, the US always swung between exceptionalism and isolationism (e.g., it did not join the International Criminal Court) and deeply-committed globalism (e.g., NATO, the UN, the IMF, the World Bank, the WHO, etc.). Politically, the latter is again something that is now a harder sell.

In short, the US choices used to be “free markets”, “free trade”, and a mixture of “globalism” and “exceptionalism”. (See Table 1.)

Under President Trump we still see “free markets”, but a shift to “protectionism” and “isolationism” or “exceptionalism”. And what Joe Biden might do? On global issues, “globalism”; there is his Made in America Green New Deal, but also opposition to the trade war – so “environmental protectionism” or “free trade”?; and on society, the talk is of an unlevel playing-field that need to be addressed – so “regulation”.

Crucially, however, none of the above resolves all of the troublesome troika:

1. Pre-Trump, it was hard to square free markets, free trade, and globalism with growing inequality. This created domestic schisms.

2. For Trump, it is hard to square free markets and protectionism with solving global problems. This creates international schisms and domestic schisms between his supporters and those preferring the status quo ante.

3. For Biden, it would be hard to square narrowing income gaps and a global approach with free trade, which means jobs can flow overseas. This implies either a form of green Trumpism on trade, or again domestic schisms.

In short, economics is not enough and we need political-economy; but political-economy cannot come up with a one-size-fits-all solution to our global problems. There ‘ism’t’ an “-ism” we can all turn to.

As a result, some will cling to the “-ism” that always works best: “utopianism”, be it nostalgia, an ostrich-like focus on ‘economics’ over politics, or dreams of one world government, one world currency, one world central bank, and one world policy to reallocate between all winners and losers.

As a mixture of all three, look no further than the central bank retreat at Jackson Hole. 27 August saw open recognition of a crisis and uncertainty…and yet only a marginal movement in the Fed’s framework of operation, this time to average inflation targeting, which will make no real difference to what even the Fed’s own staff show are deep-rooted structural, political problems.

Oprah-ism

Indeed, for now we must assume central-bankism continues unabated with no justification for that huge financial power.

That means endlessly rising markets – and endlessly rising inequality, and an underlying devolution towards post-capitalism and neo-feudalism, even if this is not visible on the surface.

If the economy does not bounce back of its own accord –and why should it?—then, with the best of intentions, central banks will be dragged deeper and deeper into interventionism with each step they take, or each government step they backstop: central banks will come to matter to Main Street as much as they do to Wall Street – if they don’t already.

That is a lot of power, and unelected and largely unaccountable.

For now, politicians –at least the ones not dreaming of utopia– are content to merely criticize central banks. How long until they realise the far greater power lies in controlling them?

Indeed, how can we have fiscal-monetary policy without the ‘political-’ wanting to join itself to the economy? This realisation will only accelerate the already evident movement towards the other zeitgeist “-ism”: populism.

As we defined back in 2019’s “The Age of Rage”, this is a catch-call term used to describe anyone who does not agree with the ‘economic’ status quo.

Does populism hold the answers? No – but nothing does.

Does it hold some of the answers? Perhaps. More importantly, ask yourself if populism is seen by voters as trying to find some of the answers, rather than just saying “It is what it is” to them.

Over time, however, and perhaps more quickly than some might expect, the “Next Normal” will arguably see the emergence of a political-economy using central-bankism –with the best of intentions– to address domestic inequality and international inequality, and to use the private sector to deliver these state goals.

Echoes of the past – and hopefully only echoes.

Or of Oprah Winfrey: “You get a car! And you get a car! And you get a car!

What’s-it-mean-for-me-ism?

In the best tradition of neoliberal capitalism, what does this mean for me? For financial markets, which have benefited hugely from central-bankism, there needs to be a recognition that gains to date have been due to just one form of political-economy – not the form of the actual economy. The threat ahead is of both political and geopolitical instability as a new status quo emerges, with polarisation before any reconciliation.

In the near term, not a lot will change. People won’t talk about political-economy; interest rates won’t go up; and markets will. Over the medium term, however, capitalism will become post-capitalism;… and then liberalism will become populism, and political-economy will come crashing back in with its own reversal of “reallocation”.

This holds out the risk of a swing from lowflation or deflation with asset-price inflation today to inflation with asset price lowflation or deflation tomorrow.

It will be interesting to watch the shape of government yield curves. The short ends are naturally low and flat, and in some cases negative too: but what will the long ends do as politics changes? Of course, this presumes they are allowed to do something. Perhaps they won’t be.

In which case, watch what the FX markets do in response. Indeed, we have seen several key EM crosses plunge versus the USD in 2020 even at a time when the Dollar itself has been under downwards pressure against developed-market crosses. Moreover, if there is no evolution in the Fed’s thinking evident and there is in other central banks, towards more easing, will USD weakness last?

Meanwhile, in terms of the economy, regulation and barriers may arise again: again, with the best of intentions. (Though some countries may adopt a populist domestic neoliberal capitalism that aggressively deregulates.)

On the trade front, however, the dynamic is much more likely to be in one direction. No political-economy with electoral appeal is likely to be able to sell free trade to net importing countries, or to ones with concerns over national security or reliance on China. This will mean far greater regionalisation and far greater geopolitical tensions during this transition, with pain falling on the shoulders of the present largest net exporters. (Ironically, however, the more countries accept a more managed, distributed global trade, the easier it will be to find a new global modus vivendi.)

Does this sound like the 1930’s economy that created the need for new political-economy in the first place, or the solution to it? That is yet to be written. Unless one is a believer in another “-ism”: fatalism.

* * *

1“Capitalism does not merely mean that the housewife may influence production by her choice between peas and beans; or that plant managers have some voice in deciding what and how to produce: it means a scheme of values, an attitude toward life, a civilization—the civilization of inequality and of the family fortune.”

Schumpeter: Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy

2 For example, in 2017, the total gross value added of Dutch companies with more than 250 employees was EUR136bn, or 37% out of EUR364bn in total. Total operating income of Dutch listed companies in that year was about EUR55bn, and stripping out Royal Dutch and Unilever it is more like EUR28bn, or just 8% of total gross value added.

3 “Nothing should be more obvious than that the business organism cannot function according to design when its most important “parameters of action”—wages, prices, interest—are transferred to the political sphere and there dealt with according to the requirements of the political game or, which sometimes is more serious still, according to the ideas of some planners.”

Schumpeter: Capitalism, Socialism, and Democracy

4 “Only if we understand why and how certain kinds of economic controls tend to paralyze the driving forces of a free society, and which kinds of measures are particularly dangerous in this respect, can we hope that social experimentation will not lead us into situations none of us want.”

Hayek: The Road to Serfdom

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3jRiccE Tyler Durden