Goldman Finds The Pandemic Recession Was Actually Not That Bad

Tyler Durden

Wed, 10/07/2020 – 20:35

In a note which we are confident will go swimmingly with millions of Americans who lost their jobs in the past six months, Goldman’s economics team writes that “scarring effect” from the pandemic recession has been “surprisingly limited” and the “damage has so far been much less than initially feared” in what is likely the most upbeat take on the current economy and one wonders if it involved any research outside of Tribeca.

After saying tthat the early weeks of the virus shock the Goldman economists “began to closely track measures of long-term damage to businesses and the labor force” with many businesses facing near-total collapses in revenue and 25 million jobs lost in little over a month, “the threat of deep scarring effects loomed over the US economy.” Instead, things have been far better than expected.

Looking at the business sector first, Jan Hatzius and team write that the “scarring effects on the business sector remain surprisingly limited” as commercial bankruptcy filings have run below the pre-pandemic trend, most business closures during the worst months of the pandemic have proved temporary, and new business formation has surged recently.

A similar cheerful conclusion emerges when Goldman looks at the labor force, with the Goldman economists writing that “scarring effects on the labor force have also been less severe than feared” , as unemployment has fallen sharply, “and most of the remaining job losers are either still on temporary layoff or are in industries that should largely recover with a vaccine.” In addition, Goldman observes, “labor demand has rebounded much more quickly than last cycle, reducing the risk of widespread long-term unemployment.”

Ludicrous? Insane? Hilarious? Perhaps all three, yet here are some of the data Goldman used to reach its arguably offensive to tens of millions of Americans conclusion:

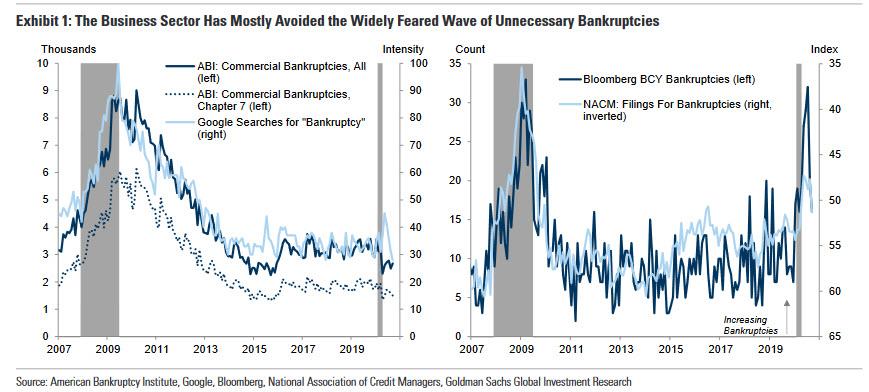

The left side of Exhibit 1 shows that total commercial bankruptcy filings reported by the American Bankruptcy Institute have actually run below the pre-pandemic trend. While a recent San Francisco Fed report noted with alarm that Chapter 11 bankruptcies are running at the fastest pace since 2013, this largely reflects recent changes to the bankruptcy code and it has been more than offset by declines in other commercial bankruptcy filings.

The right side of Exhibit 1 shows that Bloomberg’s count of bankruptcies at large companies did briefly spike to a level that approached the financial crisis peak. But as our credit strategists have shown, the majority of these were firms already on a path to default before the pandemic, not otherwise healthy businesses needlessly sunk by an unprecedented shock.

In other words, Goldman contends that while there was a spike in defaults, it was largely among those companies that were already levered to the hilt and would have filed anyway. The covid crisis merely accelerated their demise, which come to thing of it, is what the covid virus is also doing with most of the elderly people it affects and who die not so much from the virus as due to other underlying, chronic or acute conditions, whose impact is merely accentuated to the point of lethality by covid.

What about Goldman’s optimistic take on the labor market?

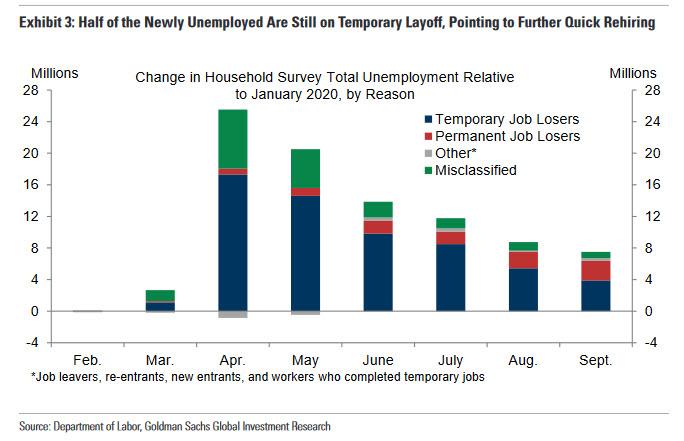

Here the economists argue that the silver lining of the employment collapse was the very high share of temporary layoffs shown in Exhibit 3, historically something which they say is “a reliable signal of rapid recovery” even as those permanently laid off is an dangerously high number, the highest since 2013, Goldman’s spin notwithstanding.

To elucidate their point, Goldman next claims that just five months later, the number of newly unemployed workers since the virus shock has indeed declined dramatically, and about half still report that they are on temporary layoff. While not all of these workers will return to their old positions, this nevertheless points to further outsized job gains in coming months.

Here Bank of America disagrees, and lays out three cyclical forces today that spell out far greater pain for the labor force than GOldman is willing to admit, to wit:

- History repeats: skill mismatch yet again. Given the lack of demand for services-travel, entertainment, etc.-there will likely end up being discouraged workers in this sector. The skills are not easily transferrable to other sectors-particularly on the goods side of the economy where demand has been resilient.

- Disengagement from the labor force due to health or childcare: the threat of the virus has left many people with extremely difficult decisions to make. Some may decide that the risk of falling sick with COVID in their workplace is too significant and thus will voluntarily leave the workforce, particularly for those who are close to retirement. Parents also struggle with child-care issues-it may be hard for parents to fully return to work until they are able to feel confident that their children can return to prior educational arrangements or daycare. This could make it difficult to have two working parents-the burden tends to be disproportionally on women. As long as the virus remains a threat, there will be a portion of the workforce on the sidelines.

- Reengagment in the labor force because of the “telepresence revolution”: over the medium-term, the shift toward greater virtual / remote working could be a positive for the LFPR. According to the BLS’s Time-Use Survey, about 8% of the workforce worked from home at least one day a week prior to COVID. According to research from the Atlanta Fed in which the authors compared the Time-Use Survey results to current survey analysis, they find that the share of working days from home is set to triple after the pandemic. Similarly, the BofA Global Research data analytics team surveyed the companies across the research coverage for their latest expectations on the timing for return to the office – the results show that only 80% of employees will be expected to be fully back in the office by the end of 2021.

While Goldman acknowledges this, saying that “not all workers who lost jobs in virus-sensitive industries will return to them when a vaccine becomes available, and many layoffs are likely to prove permanent” but then adds that “workers who have to switch jobs or even occupations already face much better prospects for re-employment than after previous recessions.”

So it’s all good, see? Well, maybe not: even Goldman had to concede that long-term unemployment rose in September and is likely to rise somewhat further in the October jobs report as more workers who lost their jobs in the first month of the pandemic cross the half-year mark. But even here Goldman finds a silver lining, and writes that “the rapid recovery of labor demand and faster pace of labor reallocation is a striking contrast with past recessions that should help most workers avoid the very long unemployment spells seen last cycle.”

In short, there is virtually nothing about the devastation endured by businesses and workers that Goldman’s well-trained economists can’t spin into a positive outcome, and as they summarize “scarring effects on businesses and the labor force have so far proven much less severe than initially feared.”

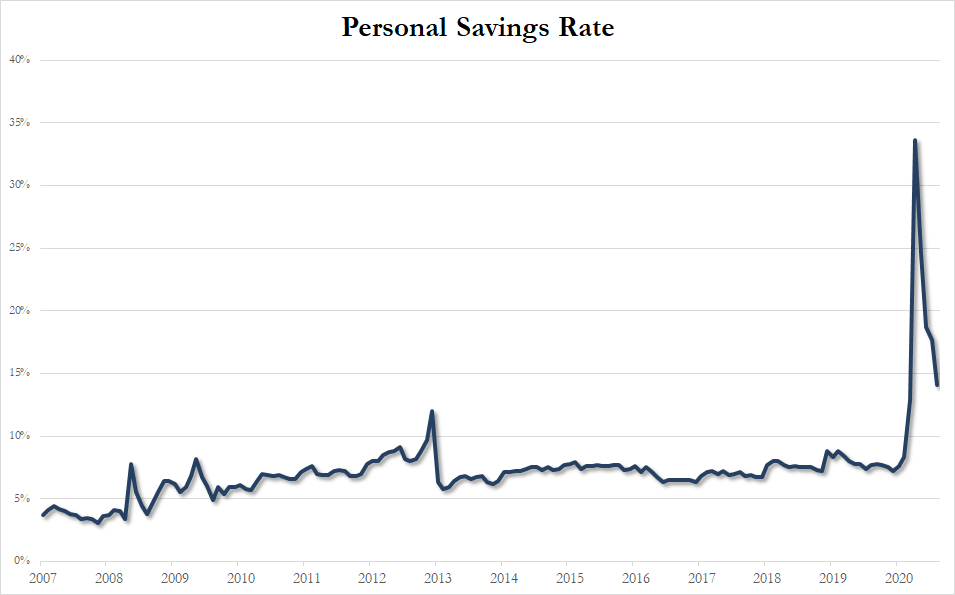

This, they conclude, “bodes well for the economy’s medium-term recovery prospects and is one more reason for Goldman’s above-consensus 2021 growth forecast.” What about the withdrawal of fiscal support which has forced Americans to draw down drastically on their savings which were boosted by the massive fiscal stimulus…

… and to resume paying down credit card debt for the first time in months?

Surely at least that has to be positive? Well, as Hatzius agrees, it does raise some risks over the next few months, but then the chief economist counters that “we expect a vaccine and further fiscal support next year—including another round of small business funding, even in a divided government scenario—to limit the long-term damage and keep the economy on track for a much more rapid than usual recovery.”

To this all one can say is wow: and while we certainly would urge the Goldman economists to read something like “A devastating experience:’ Temporary layoffs just became permanent for millions of American workers, and “Ex-Bankruptcy Judge Says Worse Is Yet To Come“, we have two questions: just why did Goldman publish such a puff piece – what does it stand to gain by gutting its reputation for at least pretend-objective analysis – and question number two: has anyone on the Goldman economics team actually stepped one foot outside their academic tri-state ivory tower in the past year?

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/36O80hP Tyler Durden