The COVID Baby Bump That Wasn’t

Authored by Michael Gartz via The American Institute for Economic Research,

The year 2020 generated several visible changes to the structure of our society. In the US, citizens migrated to different parts of the country, workers changed or lost jobs, and education became virtual.

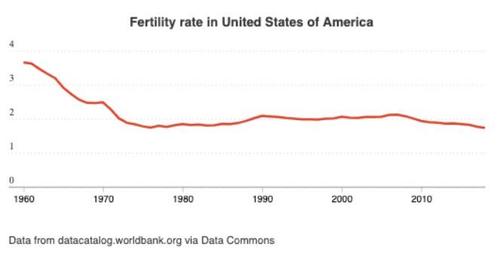

One thing, however, has not changed: despite expectations of a baby boom from idle couples locked down together, birth rates continue to fall. Birth rates were already trending downwards in Western countries as more women focused on their education and careers, thus delaying plans for marriage or starting a family. The shrinking wage gap between men and women also incentivized many women to postpone childbearing to remain in the workforce longer.

This pattern is reflected in the US, where birth rates hit a 35-year low in 2019: The CDC notes birth rates declined for nearly all age groups of women under 35, remained stagnant for those 35-39 and rose for women in their early 40s.

But when state governments initiated lockdowns in March of 2020, commentators optimistically predicted an approaching Covid baby boom set to arrive around the start of 2021 as couples sheltered-in-place together. So far though, the boom hasn’t arrived.

CBS News reports that provisional data from 29 state health departments shows that births declined by approximately 7.3% in December 2020 — the biggest decrease since the baby boom ended in 1964. In fact, 2020 saw 50,000 fewer births across Arizona, California, Florida, Hawaii and Ohio than the previous year. Hawaii experienced the most significant decline, with birth rates decreasing 30.4% leading Bloomberg to conclude that the “Pandemic Baby Boom Turned Out to Be Bust Despite Lockdown.”

So Why the Baby Bust?

1. First Comes Love

You know the old children’s rhyme about sitting in a tree, K-I-S-S-I-N-G? First comes love. Then comes marriage. Then comes a baby in a golden carriage.

Well, 2020 probably didn’t have much kissing as lips hid behind masks and dating morphed from movie dates, candlelit dinners and romantic walks along the beach to lonely nights on the sofa watching apocalyptic films (or chick flicks), screen-lit virtual dinners, and socially-distanced outdoor picnics.

Adding to restrictions on available date-night activities, 7 in 10 people believe dating is expensive: in 2019 RealSimple said “a single person spends about $168 per month on dating.” USA Today reported a study which found that 21% of millennials believe they need to reach a certain income level before pursuing a relationship, and 22% of singles said they were deterred from pursuing a relationship based on the potential partner’s financial situation.

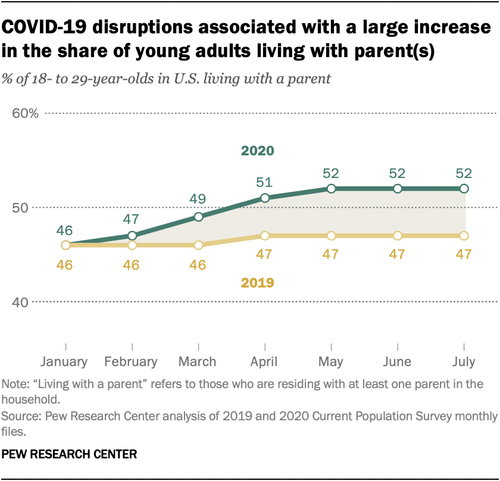

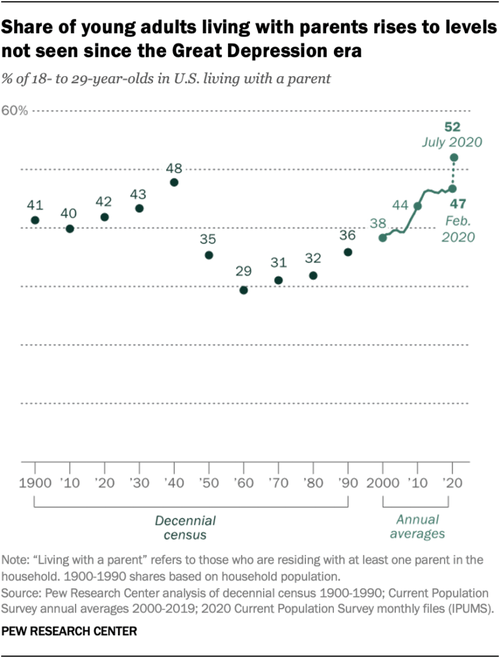

In 2020, increased financial pressures forced many millennials — adults between the ages of 24 and 39 — to move back home with their parents. Pew Research notes that financial pressures or job loss accounted for 18% of pandemic-induced moves, while 23% of young adults moved due to college campus closures. Overall, there was a 6-percentage point increase in 18-29 year olds living with parents between January and July 2020, a 5-percentage point increase from July of the previous year. Last year, the percentage of young adults living at home had surpassed Great Depression-era levels with 52% living at home by July.

Source: Pew Research

Financial pressures and alternative living situations could serve as one explanation for why there was a drop in birth rates for women in this age group.

2. Then Marriage?

If love comes before marriage, then we should expect a domino effect resulting in fewer upcoming nuptials. Weddings can take an average of 13-18 months to plan.

Under Covid, event venue cancellations, restrictions on large gatherings and inability for friends and family to travel across state and national boundaries left couples all over the world scrambling as their weddings were cancelled once, twice, three times as restrictions were implemented and later reintroduced.

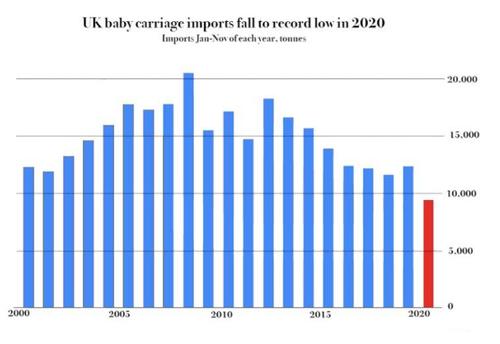

As unromantic as it is to talk about, the fact remains that marriage provides added legal and financial stability to having children. Reuters notes that in Italy, marriages fell over 50% in the first 10 months of 2020. By December, 9 months after initiating lockdowns, there was a bambino bust: births had dropped 21.6%. A decrease in the number of weddings is correlated with lower demand for baby carriages. British imports of baby carriages plunged “to the lowest level since records began in 2000.”

3. And Babies!

The 2020 restrictions on “non-urgent” and “elective” procedures served a devastating blow to the one in seven couples that have difficulty conceiving. In 2018, over 74,000 American babies were conceived through IVF, or in-vitro fertilization — a treatment which requires carefully scheduled medications and regular appointments, treats a range of infertility issues caused by problems with sperm, ovulation, endometriosis or egg quality.

The BBC reported that, last April, the UK banned all new fertility treatments. This means some couples have or will miss their last chance to conceive. “If you’re 25,” says Dr Barry Witt, a fertility centre medical director in Connecticut, “you can wait a year. If you’re 40 that’s a different story.”

The “time crunch” has led to bouts of depression, anxiety, anger and desperation amidst patients waiting to resume treatments, “because they can’t wait for a year or two because chances of success could diminish dramatically.” Dr Marco Gaudoin says that, “Statistically from the age of 34 onwards, for every month that passes your chances drop by around 0.3%. So after six months it’s [dropped] about 2%.”

4. A Lonely Road to Labor

Few people would willingly take on additional stressors during lockdowns, uncertainty and financial stress during Covid. Depriving expectant mothers of significant milestones, such as baby showers and gender reveal parties isolates them from supportive networks of friends and family essential to reducing stress and improving mood.

Stress undoubtedly increased following hospital guidance which would allow the mother to have only one visitor by her side during labor, delivery, and postpartum — in some instances visitors were banned altogether.

During a 4-day ban, one expectant mother was told that her husband would not even be allowed to enter the hospital to fill out paperwork or carry her heavy hospital bag. She reported that “[the hospital] wanted labours to move along as efficiently as possible. Instead of 48 hours, we’d only get to stay in the hospital for 24.”

Fear and stress can negatively impact the well-being of infants and development of the fetus. A 2004 study found that mothers living within 2 miles of the World Trade Center and whose infants were in utero during 9/11 had reduced birth weights, gestation periods and head circumferences (indicative of brain development) — an effect that was even more pronounced for mothers in their first trimester.

5. A Healthy Baby?

Adding to pregnancy concerns were questions about how Covid could affect embryos and developing fetuses. One New York Times article asking “Why Women May Face a Greater Risk of Catching Coronavirus” noted a CDC statement “that it has observed miscarriage and stillbirth in pregnant women infected with other coronaviruses like SARS and MERS.”

Some professionals were so cautious they told their patients to “just stay home” as IVF provider Dr. Aimee Eyvazzadeh did. She advised expectant mothers to:

avoid anything that looks like a human… sounds like a human… walk[s] like a human… or breathes like a human. Wrap yourself in bubble wrap.

During Covid, expectant mothers’ fears have only been exacerbated by headlines warning, “Pregnant Women are at Higher Risk For Severe Covid-19 And Death.” According to the article,

After adjusting for age, race, ethnicity, and underlying conditions such as diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and chronic lung disease, pregnant women were three times more likely to be admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU), and 2.9 times more likely to receive mechanical ventilation compared to nonpregnant women in the same age group.

But Forbes noted that this could also be due to the physiological changes associated with pregnancy — including increased heart rate and oxygen consumption, decreased lung capacity, and decreased function of the immune system.

6. Unemployment and Loss of Health Care

Because of increased unemployment after the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, the number of women with employer-sponsored health coverage fell for the first time. A Brookings analysis found that this “led to a large decline in birth rates, after a period of relative stability”:

In 2007, the birth rate was 69.1 births per 1,000 women ages 15 to 44; in 2012, the rate was 63.0 births per 1,000 women. That nine percent drop meant roughly 400,000 fewer births.

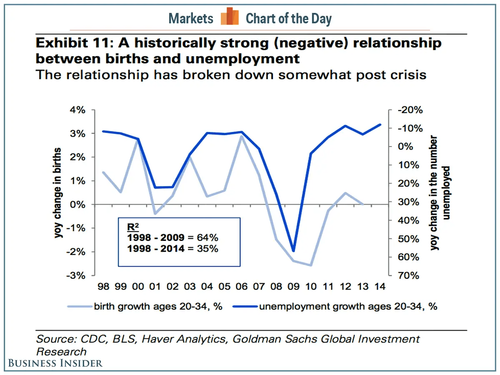

A study analyzing 40 million US birth records from 1975 to 2010 noted a similar pattern: “a one percentage point increase in the unemployment rate experienced at 20 to 24 is associated with an overall loss of 14.2 conceptions [per 1,000 women].”

And this pattern has continued during Covid. Under growing economic and social insecurity 40% of women reported in a Guttmacher Reproductive Health Survey that they have “changed their plans about when to have children or how many children to have.”

According to KFF, 61% of American women aged 19 to 64 (i.e. 59 million females) had employer-sponsored health insurance coverage in 2019. But, as my colleague Amelia Janaskie wrote, women have been disproportionately affected by the 2020 lockdowns because they make up a greater portion of in-person service industries for which teleworking is less feasible.

Uninsured women often have inadequate access to care, get a lower standard of care when they are in the health system, and have poorer health outcomes. Healthcare coverage is essential to help cover medical costs of pregnancy, such as ultrasounds, prenatal tests and care — costs that can quickly add up.

7. The Baby’s Drinking Alcohol

Babies remain expensive until adulthood. In 2019 the average cost in most US states for a vaginal birth was $5,000–$11,000 and $7,500–$14,500 for a cesarean (assuming there are no complications during birth).

Depending on location and household income, new parents can expect to spend $20,000 to $50,000 during the first year of their newborn’s life. And New York Life wrote in 2015 that middle-income households could expect to spend between $12,350 and $13,900 on their children annually up to age 17. With job insecurity being high in 2020, the added cost of childbirth could be infeasible to many women.

* * *

Covid has only exacerbated a downward trend in birthrates; Brookings expects to see between 300,000 and 500,000 fewer births in 2021. The social impacts of such a significant demographic shift will be enormous.

Tyler Durden

Wed, 05/12/2021 – 19:40

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3uMpwMg Tyler Durden