Cults are in style again. Or at least it’s trendy to call things cults—everything from QAnon to SoulCycle has gotten the tag. It’s pretty easy to throw the word around loosely, since we’ve never come to a consensus about what exactly a cult is.

The line between “cult” and “religion” is famously hazy, and the biggest practical distinction between the two is whether a faith has been here long enough that you feel comfortable having it around. If you’re especially apprehensive about rival sects, even longevity might not be enough to get a group off the hook. “The difference between a religion and a cult,” The Globe and Mail cracked in 1979, “is that you belong to a religion and everyone else belongs to a cult.”

Some scholars dismiss the c-word as a slur, preferring the less pejorative term “new religious movement.” Others say a cult is distinguished not by whether a group is new but by whether it has a particular sort of authoritarian internal culture, a scope that excludes many of those new religious movements but includes several organizations that aren’t ordinarily thought of as religious at all: pyramid schemes, psychotherapy groups, would-be vanguard parties. Some sociologists have tried to advance a more neutral approach, suggesting that cults are held together by a living charismatic leader while other religions rely on an established set of rituals and doctrines. (Under that definition, you might note, a circle of harmless high school occultists might qualify as a cult but Scientology arguably ceased to be one years ago.)

And in ordinary conversations, those all get mixed together. At some moments, the word cult can encompass any exotic way of looking at the world; at others, it’s a set of social dynamics involving unhealthy hierarchies and rigid attachments to a party line. Often it entails looking at the former and imagining that you’re seeing the latter. At its most feverish moments, it involves seeing the alleged cultists not merely as people who happen to have a different view of the world, nor even merely as the victims of an abusive leader, but as zombies who have lost the capacity to think or act for themselves.

Fortunately, we don’t need to settle on a definition here. Our subject isn’t cults themselves so much as the monsters people imagine when they hear the word.

America has always been haunted by cults, but the hauntings are more acute at some times than others. “From the 1970s through the 1990s, from Jonestown to Heaven’s Gate, frightening fringe groups and their charismatic leaders seemed like an essential element of the American religious landscape,” Ross Douthat wrote in The New York Times in 2014. “Yet we don’t hear nearly as much about them anymore, and it isn’t just that the media have moved on. Some strange experiments have aged into respectability, some sinister ones still flourish, but over all the cult phenomenon feels increasingly antique, like lava lamps and bell bottoms.”

Seven years later, it is Douthat’s diagnosis that feels antique. Cults themselves may or may not be more common now than in 2014, but we’re awash in a flood of cult stories, cult rumors, and cult rhetoric. It’s still “nothing like where things were in the early ’90s,” says J. Gordon Melton, a professor of American religious history at Baylor. But “dislike of cults has never really gone away…and we’ve seen a heightening of that over the last couple of years.”

Let’s start with the small screen, which has offered plenty of cult-themed materials for binge watchers in lockdown—and not just in purely fictional tales like Riverdale or The Empty Man. Last year Starz and HBO each ran their own documentaries about NXIVM, a purported self-help group charged with being a front for a secret society devoted to sex slavery. Curious viewers could turn from there to Netflix’s Wild Wild Country, a six-part 2018 docuseries about Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh’s ashram in Antelope, Oregon, and the conflict that erupted in the ’80s between his followers and the townsfolk nearby. If you developed a taste for the subject, you had several other documentaries from the last few years to choose from, covering vintage cult stories ranging from the Peoples Temple massacre of 1978 to the Heaven’s Gate suicides of 1997. A&E ran three seasons of a series about Scientology.

The subject keeps cropping up in the news too, with alleged cult crimes committed everywhere from Idaho to Siberia. (One of the first COVID-19 superspreader events in Korea took place at the Shincheonji Church of Jesus, an apocalyptic sect that is often accused of being a cult. That sparked conspiracy theories in which the church was supposedly spreading the virus to deliberately bring on doomsday.) Using the GDELT Project’s Television Explorer tool to search the Internet Archive’s TV News Archive, one can detect a systematic increase in the use of the word cult since November 2019. Sometimes that’s because of those local stories, but the term turns up in broader contexts too.

Take QAnon, a sprawling subculture devoted to a strange, elaborate, and ever-evolving collection of conspiracy theories. Conspiracism in general has attracted a lot of anti-cult rhetoric lately—when one poet was disturbed by her elderly mother’s interest in conspiracies, she wrote in The New York Times last year that it was “as if” her mom was “under the spell of a cult”—and QAnon has gotten the brunt of this. Many of its critics call it a cult, sometimes even a “terrorist cult.” In March, NPR ran a story suggesting that QAnon and similar beliefs are “cultic ideologies” whose followers could use the help of “deprogrammers” to “reconnect with reality.” The Q believers, for their part, are convinced that a cult of cannibal pedophiles controls most of Washington and Hollywood.

The fringy Q crowd weren’t the only ones who suspected a cult had taken over the country. As Donald Trump’s presidency progressed, it became increasingly common to hear his following described as a cult. (During the pandemic, this sometimes progressed to “death cult.”) This wasn’t always meant as mere metaphor: In late 2019, a major American publishing house—Simon & Schuster—put out a book called The Cult of Trump: A Leading Cult Expert Explains How the President Uses Mind Control, written by the anti-cult activist Steven Hassan.

When some of those Trump fans rioted at the U.S. Capitol on January 6, 2021, it wasn’t just the outgoing president’s opponents who embraced that rhetoric. One defense attorney—Clint Broden, retained by the accused rioter Garret Miller—went on TV to announce that he’s working to “deprogram” his client. “Donald Trump was a cult leader,” Broden told CNN’s Chris Cuomo. “You have somebody like Garrett Miller, who is not very politically involved, hadn’t even voted much earlier in life, loses his job, and gets focused on the internet. And you have, as I said, a cult leader telling him to do X, Y, and Z to protect the country.” Ordinarily, people think it an affront to their dignity to be depicted as a mindless sheep. But under certain circumstances, it can be a useful way to deflect responsibility.

Inevitably, the specter of the cult entered other fronts of the culture war. “Wokeness,” Fox News, both major political parties: They’ve all been called cults in the last few years. And then there’s the battle over trans rights, where the rhetoric has been getting especially ugly.

Parents have long been prone to moral panic when adolescents embrace ideas or subcultures that seem alien. One perennial way to express those anxieties is to say their children have “joined a cult,” even when no actual organization is in sight. This reached a new height of hysteria when certain conservatives and feminists started describing transgender teens in terms that evoke Jonestown. Google the phrase trans cult and you’ll find countless complaints that a complex social world with no leader, no clerical hierarchy, and no shortage of substantial internal disagreements is in fact a cult bent on “stealing our children.” Mutual support is seen as “love bombing,” interest in new ideas as “brainwashing.” The same anti-cult writer who produced The Cult of Trump tweeted last year that trans advocates are using “weaponized mind control” to recruit young people.

One anti-trans group, the Kelsey Coalition, chose these words to represent a parent’s experience: “Your beloved child has been kidnapped by a sadistic cult. The cult brainwashes her to believe you are the enemy. The brainwashing erases her entire childhood. Every good memory is replaced with memories of abuse that never happened. The cult convinces her to inject poison in her body and to get her healthy body parts amputated. You panic. You scream. You sob. You beg. You are reduced to nothing. You search for help everywhere. Nobody will help. Nobody will stop the cult.”

It’s an extreme example, but it isn’t an especially unusual one. Here’s an assortment of phrases from Abigail Shrier’s book Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters (Regnery): “Her mother said it seemed as though Lucy had joined a cult.” “What she escaped—she insists—was a cult.” “When you have a daughter that’s really indoctrinated—and it’s almost like a cult really…” “I was so brainwashed.”

‘The Mind…Can Never Afterward Be Free’

America has always been haunted by cults because America has always been a land of cults. If you wanted to find a home for a new religious movement, this spacious continent was a pretty good place to do it. Some of the first European colonists to put down roots here were spiritual dissidents looking for a place to build an ideal community, and that process of exit and renewal didn’t stop once the first colonies were settled. A Pietist village in rural Pennsylvania, a spiritualist enclave in upstate New York, a Mormon territory out west, an Iowa town devoted to transcendental meditation: Lots of flocks have found spots to settle.

If you weren’t a part of the flock, the flock might scare you. The Jacksonian era, a period that stretched from the 1820s to the years before the Civil War, saw both a wave of immigrants from Catholic Ireland and a religious revival at home. The latter was marked by frenzied camp meetings and by a wave of new sects; while nativists were imagining the Irish as puppets manipulated by the Vatican, many Americans adapted those myths to make sense of young faiths and new worship styles.

One 1836 tract by a Presbyterian minister presented the revival preachers of the Second Great Awakening as hypnotists brainwashing Americans en masse, declaring that worshippers’ minds were “compelled, in a moment of the greatest possible excitement, to yield themselves entirely—their intellect, their reason, their imagination, their belief, their feelings, their passions, their whole souls—to a single and new position, that is prescribed to them….The mind, reduced to such a bondage, can never afterward be free.” Over the course of the century, the Mormons were accused of an assortment of cult crimes, including hypnotizing women into joining Mormon harems. And then there were the Shakers.

The United Society of Believers in Christ’s Second Appearing, as the Shakers are formally known, first came to America not long after their faith was founded in 18th century England. Here they lived in communes, refused to fight in wars, refused to have sex, and built rituals around ecstatic trance dancing. Sometimes, rumor had it, they did that dancing in the nude. All this alarmed some of their neighbors, as did broadsides accusing the group of recruiting new members with mesmerism and then enforcing their control with physical violence. Outsiders sometimes mounted “rescue” missions, seizing children who were supposedly being held against their will. (Some of those kids went home as soon as they got a chance.)

The pattern periodically repeated itself. In his 2000 book Mystics and Messiahs, the historian Philip Jenkins points out parallels between two waves of cult interest, one starting around 1910 and the other beginning in the 1960s. Each opened, he writes, with “surging interest in fringe religions and the occult” and the “creation of many new marginal groups and sects.” After about a decade and a half of this, there was a “wave of scandals” involving those groups’ leaders, which was framed as a “cult problem” in popular culture. That in turn produced “sensational media-led speculations.” In the 1930s, this meant tales of “voodoo, witchcraft, human sacrifice”; in the 1980s, it involved supposed Satanic murders and ritual sexual abuse.

The word “cult” didn’t really start to come up in these contexts until the early 20th century, and it didn’t fully take on its current connotations until the cult scare of the 1970s was well underway. As late as 1972, the British sociologist Colin Campbell could describe cults as “individualistic and loosely structured,” adding that “the cult makes few demands on its members, is tolerant of other organizations and faiths and is not exclusivist”—almost the exact opposite of the way the word was widely used at the end of the decade, when cultists were imagined as dogmatic robots serving iron-fisted leaders.

The roots of the ’70s cult scare go back to the aftermath of World War II. America is always generating new sects, but during the war “there was kind of a pause,” says Melton. “The major people who start new religious groups are people from the 18–25 group, the exact group that they pull out and take overseas.” In the postwar period, some of that pent-up activity poured out, and that then intensified during the cultural revolutions of the ’60s.

Those same revolutions launched a wave of communes, with tens of thousands of young people forming small-scale experiments in collective living. Most of these dissolved pretty quickly, but some held on, and many of the ones that survived were built around a charismatic figure—the sort of person an outsider might call a “cult leader.” Meanwhile, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 opened the country to a greater number of Asian spiritual groups, many of which seemed strange and threatening to traditional American Christians.

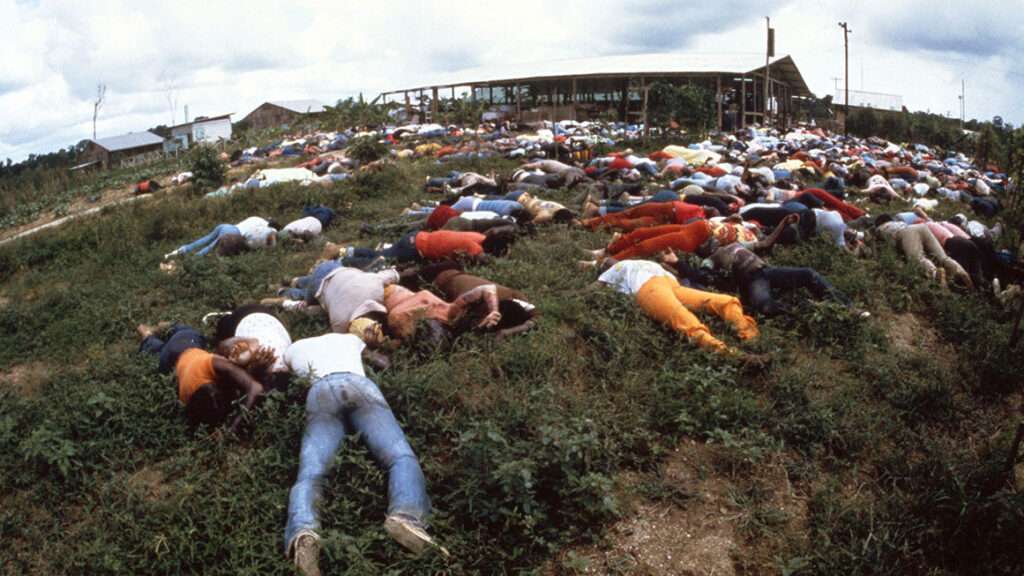

With some new religious movements, of course, Americans had good reasons to feel threatened. The most infamous was the Peoples Temple, a radical church founded in Indianapolis in the ’50s by the Rev. Jim Jones. He moved it in 1965 to California, where it eventually embedded itself in the San Francisco political establishment. He also founded a colony in Guyana, officially known as the Peoples Temple Agricultural Project but better known by its nickname: Jonestown. It was there, on November 18, 1978, that Jones announced that the community’s enemies were closing in and ordered his followers to go out with an act of Masada-style defiance, by killing themselves and their children. More than 900 people then drank a cyanide-spiked punch and died.

They drank that Flavor Aid while surrounded by armed guards, and the event was a mass murder as much as it was a mass suicide. Nonetheless, the story was widely remembered as a straightforward tale of automatons dying on command. The massacre cemented a stereotype: After 1978, the word cult connoted a charismatic guru leading a tight-knit, highly hierarchical, rigidly doctrinaire sect that drew in young people, brainwashed them, subjected them to sexual and financial exploitation, and just might compel them to commit suicide. In literature from the era, you’ll often see the Peoples Temple listed side by side with such nonthreatening groups as the Baha’i faith or the Esalen Institute.

That sort of blending was especially common in the “counter-cult” movement, which differed from its more secular anti-cult counterparts by being chiefly interested in fending off challenges to Christianity. In his 1982 book Those Curious New Cults in the 80s, for example, William Petersen starts a chapter with the gruesome tale of Jonestown, then explains that while a “few” cults might follow in the Peoples Temple’s footsteps, “most are laced with more subtle dangers than cyanide.” Before long he is discussing astrology and the I Ching, which aren’t organizations at all, let alone sects led by a charismatic founder-prophet.

The best encapsulation of the counter-cult approach might be “Oh Buddha,” a song by the Imperials that topped the gospel charts in 1979. Without ever actually using the word cult, its chorus casually jumbles the Hare Krishnas and the Moonies with Buddhism and Islam, zeroing in on one of the few things the two age-old faiths had in common with the new movements—the singers didn’t recognize them as Christian: “No it won’t be old Buddha that’s sitting on the throne / And it won’t be old Muhammad that’s calling us home / And it won’t be Hare Krishna that plays that trumpet tune / And we’re going to see the Son, not Rev. Moon.”

The Van Helsing of the cult scare was a figure known as the deprogrammer. The word reflected the idea that cultists were not really in control of themselves: that they had been programmed by someone else, and that this programming had to be removed before they could once again be regarded as fully self-governing individuals. In its most extreme forms, the deprogramming process might entail forcibly seizing the believer and subjecting her to a constant drumbeat of propaganda—a funhouse-mirror reflection of the brainwashing purportedly conducted by the cult itself.

Inevitably, deprogrammers who did this were denounced as an “anti-cult cult.” They weren’t the only ones: Periodically you’ll read about disillusioned members who leave a group, accuse it of being a cult, form a support group for other exiles, fall into intense and perhaps toxic behavior, and soon face accusations that their new group is a cult too. Being deeply opposed to cults does not confer immunity against cultish behavior.

‘Odds Are This Is Happening in Your Town’

Many tropes of the ’70s cult scare were eventually debunked. While individual sects could be coercive, manipulative, or otherwise exploitative, just as older faiths can be, many new religious movements were guilty simply of seeming strange. Serious scholars mostly rejected the idea of brainwashing, and the ones who hung on to the concept denied that it was some sort of mind control technique. (One of the word’s defenders, the Rutgers sociologist Benjamin Zablocki, describes brainwashing merely as “well-understood processes of social influence orchestrated in a particularly intense way.”) Real-world cultists were not zombies.

But then, not all the cults that people feared actually existed in the real world.

As the ’70s gave way to the ’80s, an idea once largely confined to conservative Christian circles seeped into the mainstream: the Satanic cult. I don’t mean public organizations like the Church of Satan or the Temple of Set, though they were often drawn into the discussion; I mean a rumored covert world of secret Satanic sects that supposedly engaged in human sacrifice and in the ritual sexual abuse of innocent children. This fantasy was uncritically endorsed in much of the media, with coverage on programs ranging from 20/20 to The Oprah Winfrey Show. (“Estimates are there are over 1 million Satanists in this country,” Geraldo Rivera warned on one program. “The majority of them are linked in a highly organized, very secret network….The odds are this is happening in your town.”) Worse yet, the fantasy took hold among police, prosecutors, and juries.

Disturbed people who commit crimes do sometimes spout Satanic mumbo jumbo. So, for that matter, do a number of people who are neither disturbed nor criminal. But there has never been serious evidence that there are anywhere near a million Satanists in America, let alone that they have formed a vast secret network that commits ritual rape and murder.

There was no role for the deprogrammer here, since the cults in question did not actually exist. But the deprogrammer’s cousin, the sketchy hypnotherapist, stepped into the breach, guiding children to “remember” horrifying crimes. Years later, some of those kids would recant their testimony. In the meantime, more than a few Americans were sentenced to long prison terms for offenses that almost certainly never happened.

There were a few other high-profile cult stories in the 1990s, most notably a lethal 1993 siege near Waco, Texas. That began when the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms became convinced that the Branch Davidians—a spinoff from a spinoff from the Seventh-Day Adventists—were stockpiling illicit weapons. There was in fact little evidence that the group’s weapons were illegal, and in any event there were several easy, nonconfrontational ways to arrest the church’s leader. Instead, armed agents invaded the Davidians’ center and the Davidians shot back, killing four feds and starting a 50-day standoff that ended with an FBI raid, a fire, and nearly all the Davidians dead. The FBI raid was approved by Attorney General Janet Reno, who in her days as a Miami prosecutor had overseen one of the better-known ritual-abuse cases of the Satanic Panic era. She signed off on the Waco order, she explained, because she believed “babies were being beaten.”

At the time, much of the media’s coverage focused on the idea that the Branch Davidians were a dangerous, irrational cult; news reports were filled with tales of weird rituals and sexual depravity. Afterward, as it became clear just how destructive the feds’ decisions had been, some officials and reporters started to reconsider the post-Jonestown assumptions that had guided the government’s approach to the conflict and the press’s approach to the story.

Meanwhile, the anti-cult movement lost a big battle in 1995, after a young man named Jason Scott sued the deprogrammer Rick Alan Ross and the Cult Awareness Network (CAN) for depriving him of his civil rights. Scott’s mother had hired Ross, at CAN’s recommendation, to save her teenaged kids from a Pentecostal congregation called the Life Tabernacle Church. In Scott’s case, this involved kidnapping him, tying him up in the back of a van with duct tape over his mouth, driving him to a remote cottage, holding him prisoner for several days, and berating him until he pretended to be persuaded. In the ensuing criminal case, Ross was found not guilty of unlawful imprisonment, though two heavies he had hired were convicted of coercion. But in the civil case, they were all hit with heavy punitive damages.

The verdict both bankrupted CAN and made it clear that coercive deprogramming could face severe legal consequences. Today’s descendants of the old deprogrammers call themselves “thought reform consultants” and present themselves as offering a voluntary, nonconfrontational approach.

Cult fears still flared up around particular events, as when 39 members of the UFO group Heaven’s Gate killed themselves in 1997, believing that this would allow them to ascend to a spacecraft near the comet Hale-Bopp. But the moral panic that had started surging in the ’70s was over. By the early 21st century, cults were more likely to turn up in horror movies than in the network news.

“When have we had a cult scare on anything like traditional lines?” Jenkins wrote in Patheos in 2014. “Yes, there have been plenty of local concerns and investigations, by strictly local and regional media….But compared to the 1970s, the cult issue has vanished almost entirely. When did you last see the once-familiar media story about Group X with exposés of its sinister guru, with tragic images of weeping parents wondering how their child could have become associated with this dreadful organization?”

A few years have passed since he wrote that, and now we’re seeing those stories again. But in an unexpected reversal, the articles today are just as likely to feature young people weeping about the choices made by their parents.

‘No Idea They’re Dabbling in QAnon’

In the summer of 2020, the website Mel ran the headline “‘WE ARE YOUR FAMILY NOW’: WHAT IT’S LIKE TO LOSE A LOVED ONE TO QANON.” The article’s opening called QAnon a “right-wing conspiracy cult,” and the next paragraph declared that “the cult’s indoctrination includes pulling vulnerable people away from their families and loved ones.” Two of the three tales that followed involved women in their 20s who felt alienated from their Q-obsessed moms.

Outlets from NPR to HuffPost to The Guardian have run similar stories. It is common in such reports, and in Q coverage in general, for people to compare QAnon to a cult. Even Rick Alan Ross, the man whose role in a kidnapping provoked the court case that bankrupted the Cult Awareness Network, has surfaced in several articles about Q: Cosmopolitan, Vice, The Daily Beast, Insider, Upworthy, and The Daily Dot have all quoted him as a “cult expert,” a “cult intervention specialist,” or some similarly neutral description. (He’s been popping up in non-Q stories too, including a New York Times piece that described him as an “expert on persuading people to leave cults.” I can think of a jury that would disagree with that.)

Yet QAnon doesn’t look much like the popular stereotype of a cult. It has no charismatic leader and little hierarchy, and its followers are free to create their own doctrines. It isn’t even always clear who counts as a member.

The QAnon phenomenon emerged from the message boards of the website 4chan, where anonymous figures claiming to be knowledgeable insiders regularly posted under names like “FBIAnon” and “CIAAnon.” On October 28, 2017, they were joined by the writer or writers who would soon be known as Q. The first canonical Q post declared that former presidential candidate Hillary Clinton was about to be arrested and that the National Guard was mobilizing to contain any violence that might follow. This forecast’s failure to come true did not deter Q from continuing to post, though it may have played a role in changing Q’s style of posting: There were fewer clear-cut predictions and more gnomic clues left for Q’s fans to decipher.

A subculture grew up around those clues, as people traded interpretations and created storylines. (Some of those interpreters were almost certainly operating with their tongues in their cheeks, spinning absurd ideas that still sometimes managed to find sincere believers.) Many of the speculations that get attributed to QAnon, such as the idea that John F. Kennedy Jr. is secretly alive, emerged from that subculture, not directly from Q.

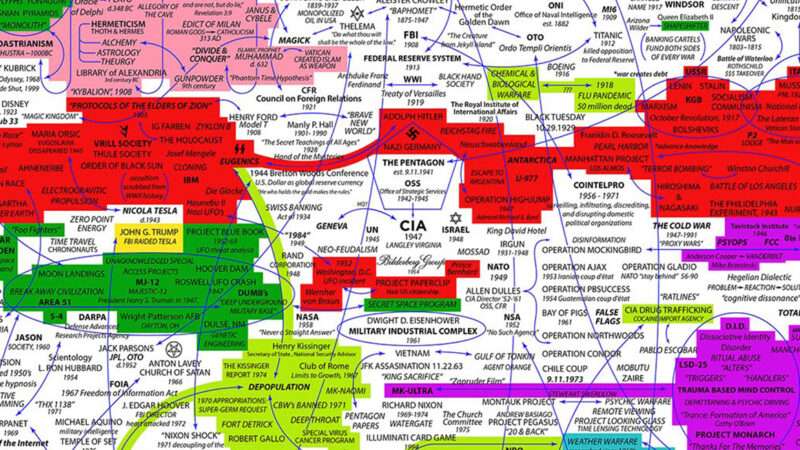

QAnon’s core narrative held that the government and the culture industry are in thrall to a cabal of Satanic pedophiles, that this cult ingests children’s blood to achieve eternal youth, and that one day Donald Trump would vanquish these villains in a sweeping crackdown, dubbed The Storm. If you think this sounds similar to the stories that circulated during the Satanic Panic of the ’80s and ’90s, you’re right.

That isn’t the only debt that QAnon owes to earlier conspiracy lore. The central horror of the story—the idea that a cabal is consuming children—is much more ancient: It is the centuries-old blood libel in which Jews, and sometimes other groups, are accused of ritually murdering children and devouring their blood. (While the anti-Semitic version of this story has been the most persistent and pervasive, Catholic authorities also aimed such accusations at heretics and, later, Protestants.) The more precise configuration embraced by the Q crowd, in which the cannibal cabal consists of Luciferian pedophiles in positions of power, could be seen at the outer edges of the Satanic Panic, as conspiracists speculated that the alleged devil-worshipping cult had infiltrated the government.

Long before any Q posts existed, books like 1995’s Trance Formation of America and 1999’s Thanks for the Memories promoted this idea. The latter, subtitled The Memoirs of Bob Hope’s and Henry Kissinger’s Mind-Controlled Slave, claimed that a network of child molesters covertly controls Washington and Hollywood, that this group uses a mixture of occult rituals and mind control technology to abuse children, and that one of these rituals involves sacrificing people and ingesting them. (This, the perpetrators allegedly believed, “would transfer the energy or life force from the victim to them in order to make them more powerful.”) During the 2016 election, such fears surfaced again in the “Pizzagate” rumor, which now put Hillary Clinton at the center of the story.

Meanwhile, conspiracy yarns about child abuse were taking hold in the mainstream. Part of this reflected events in the news that really did involve powerful people having sex with minors while other powerful people looked the other way—the Jeffrey Epstein and Jimmy Savile scandals. But the stories circulating went well beyond that, as officials and nonprofits exaggerated both how common and how organized sex trafficking is. A 2001 paper, for example, offered a very rough estimate that more than 300,000 kids belonged to one of several categories—runaways, minors in public housing, etc.—that made them more likely to be trafficked. This already shaky figure was frequently presented as the number of children “at risk” of being trafficked, and that in turn was sometimes garbled into the number of children being trafficked.

Against that backdrop, age-old urban legends adapted themselves to the Facebook era, with worried parents sharing unlikely tales of close encounters with child-snatching gangs. Local news outlets sometimes uncritically amplified these rumors. All that helped pave the way for QAnon: It was easier to believe in a vast pedophilic conspiracy if mainstream sources were constantly telling you that conspiracies of pedophiles were everywhere.

When the Q posts started in late 2017, they lifted ideas freely from other stories circulating among the anons. Even one of the most distinctively bizarre Q concepts—the notion that Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation of Donald Trump was just a cover story and that Mueller and Trump were secretly working together to take down the pedophile cabal—had already appeared on 4chan shortly before Q’s debut. As time passed, QAnon’s loose, collaborative structure allowed the theory to grow ever more baroque: All sorts of ideas could be attached to the growing mythos, and Q fans could adopt or reject them as they saw fit. In this way, QAnon absorbed older conspiracy tales.

As the press became increasingly alarmed about Q, this history sometimes got scrambled: QAnon was identified as the source of ideas that in fact had emerged elsewhere, and people who espoused those older stories were misconstrued as extensions of Q. USA Today ran an article warning that Q-ish notions were “gaining traction among people who have no idea they’re dabbling in QAnon,” but literally all of the article’s examples had emerged independently of QAnon. A New York Times piece claimed that “scores” of Republican candidates were “cherry-picking the movement’s themes, such as claims that Jews, and especially the financier George Soros, are controlling the political system and vaccines; assertions that the risk from the coronavirus is vastly overstated; or racist theories about former President Barack Obama.” The only one of those ideas that didn’t predate Q is the one about the coronavirus, and it didn’t exactly need QAnon’s help to take off. Another New York Times story declared QAnon the “root” of Trump’s claim that “people that you haven’t heard of” are controlling Joe Biden. At the risk of stating the obvious: The belief that politicians are controlled by people you haven’t heard of is one of the oldest conspiracy concepts around.

This confused approach may have reached its apex in September 2020, when Civiqs released a poll that seemed to show 56 percent of Republicans believing either that QAnon is “mostly true” or that “some parts” are accurate. It sounds staggering until you see how the question was worded: “Do you believe that the QAnon theory about a conspiracy among deep state elites is true?” If you’d vaguely heard of QAnon, didn’t know the labyrinthine details, and had just heard it described as “the QAnon theory about a conspiracy among deep state elites,” with no reference to the Q world’s weirder beliefs, you might well answer yes to signal your belief that deep state elites conspire.

“The question conflates concepts about the existence of a ‘deep state,’ animosity towards ‘elites,’ and the existence of a general ‘conspiracy’ with QAnon,” says Joseph Uscinski, a political scientist at the University of Miami who regularly conducts polls on the popularity of different conspiracy theories. “Respondents could therefore be answering yes to any of those without knowing what QAnon is or what its ‘theory’ is.” Uscinski’s polls put Q’s support in the single digits; one that he took not long after the Civiqs survey found 6.8 percent identifying as Q believers. When Civiqs did a follow-up poll, it took such criticisms into account, rephrased the question, and found Q’s support at 7 percent. (Among Republicans, the number was 14 percent.) Another poll, conducted by the Tufts political scientist Brian Schaffner, added an extra twist. Schaffner didn’t just find that 7 percent of the country backs QAnon; he asked about four specific conspiracy theories at the heart of the Q narrative. Turns out that the average QAnon backer hadn’t heard of most of them and believed in only one.

Why does this matter? Because those articles overstating the size of QAnon coexist with another set of articles—sometimes another set of passages in the same article—that discuss psychologically disturbed Q believers who have committed acts of violence. That’s bad enough when it implies that the majority of Q fans are ticking time bombs. When you’re also defining QAnon overbroadly, you’re seriously inflating the threat.

Similarly, Q coverage regularly claims that the FBI has designated QAnon a “domestic terror threat.” This is untrue: The intelligence bulletin in question was about conspiracy theories in general. It said that such theories are sometimes linked to violence, and it gave some examples, some of which involved Q fans and some of which did not. It did not single out QAnon as being particularly dangerous, and it did not designate its followers as a terror group—nor could it. “The federal government does not have a legal mechanism to officially designate a domestic group as a terrorist organization,” says Michael German, a former FBI agent now affiliated with the Brennan Center for Justice’s Liberty & National Security Program. “I’m sure certain individual adherents to the movement may have committed criminal acts,” he adds, “but attributing that to an entire organization is improper.”

For all its dehumanizing rhetoric about its enemies, QAnon was probably less prone than other conspiracy theories to lead believers toward violence. The orthodox Q position was to sit back and “trust the plan”; The Storm was going to be a smoothly executed Trump Ex Machina, not a participatory uprising. (In the words of one early Q post: “No war. No civil unrest. Clean and swift.”) These things can mutate, of course. After The Storm failed to happen, it was easy to imagine disappointed Qers taking things into their own hands—and sure enough, Q devotees were well-represented at the Capitol riot. But among right-wingers ready to take up arms against their enemies, QAnon is frequently derided for encouraging people to be passive. Where liberals are alarmed by Qers’ religious fervor, these militants are more likely to see Q as the opium of the Trumpite masses.

‘A Constant Feature of Society’

Violent or not, QAnon doesn’t have much in common with the groups that usually jump to mind when someone says “cult.” But there is one way that word might help make sense of Q. It involves an older use of the term—the one Colin Campbell was deploying in 1972 when he called cults “individualistic and loosely structured.”

Campbell proposed the existence of a “cultic milieu.” This “cultural underground,” he argued, “is continually giving birth to new cults, absorbing the debris of the dead ones and creating new generations of cult-prone individuals to maintain the high levels of membership turnover. Thus, whereas cults are by definition a largely transitory phenomenon, the cultic milieu is, by contrast, a constant feature of society.” The heterodox ideas that circulate there include “the worlds of the occult and the magical, of spiritualism and psychic phenomena, of mysticism and new thought, of alien intelligences and lost civilizations, of faith healing and nature cure.” While these notions thrive underground, they do not always stay there: Forces ranging from astrology columns to Oprah guests have beamed them into the mainstream. (In 1970, Martin Marty called such transmission belts the “occult establishment,” a phrase that today sounds like something out of QAnon.)

Campbell’s original essay didn’t discuss it, but there is a cultic milieu in politics too. The political world has its own underground of unconventional ideas, which at times intersects with Campbell’s underground of mystics. Some of the most creative and fruitful political thinking takes place there, and so does a lot of pure lunacy. Its denizens sometimes float from one identity to another, taking paths that puzzle people used to the conventional left/right spectrum: An anarcho-capitalist becomes a tankie, an Occupier enters the alt-right, a devotee of holistic health turns to Q.

Some of these ideas and identities are long-lived, some are transitory, and some keep recurring in new forms. In a study applying the cultic-milieu model to radical environmentalists, Bron Taylor devoted a few paragraphs to “militant autonomous zones”: areas where “anarchist squatters establish themselves and attempt to keep out what they consider to be the repressive authority of the nation state.” Taylor published that paper in 2002, nearly two decades before the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone surfaced in Seattle.

Q’s posts have become infrequent since the election. (At press time, the most recent one appeared on December 8, 2020.) Some Q followers have fallen away from the faith since Biden became president, while others have gamely tried to conjure up explanations for why Trump appeared to leave office without a mass arrest of child abusers. Maybe those explanations will attract enough adherents to keep QAnon alive, or maybe we’re finally about to see the movement break down and disappear. Lately, many voices in the Q world have taken to rejecting the word QAnon, even as they hang on to much of the mythos. But even if the movement does go away, the cultic milieu that produced it will not. QAnon emerged from the debris of older stories about Satanists, powerful pedophiles, and bloodsucking cults. Someday, something else will emerge from the debris of Q.

‘The First Effect of Not Believing in God’

In his 1997 book Modernization and Postmodernization, the political scientist Ronald Inglehart observes a broad, cross-cultural change. In dozens of countries, he concludes, survey data show people more inclined to challenge “all kinds of authority” and to exalt “autonomy in the pursuit of individual subjective well-being.” This, he argues, reflects a step beyond modernization: a process he calls postmodernization. “A central component of Modernization was the shift from religious authority to rational-bureaucratic authority,” he writes. “A major component of the Postmodern shift is a shift away from both religious and bureaucratic authority.” Having eroded traditional institutions, modernity goes on to erode the dominant institutions of modernity itself.

There’s a line often attributed to the Catholic writer G.K. Chesterton, though he doesn’t seem to have said it: “The first effect of not believing in God is to believe in anything.” When trust in the old authorities decays, many people look for substitute certainties—an unfortunate but probably inevitable byproduct of the same renewal process that allows less rigid, less hierarchical alternatives to emerge. Some of those substitute certainties feature dubious dogmas, charismatic leaders, and an overwhelming demand for group loyalty. In other words, they look like cults.

America has always been haunted by cults, because modernity and then postmodernity have been disrupting American institutions for centuries. But in certain periods the disruption has been particularly potent. One was the Jacksonian era. Another was the upheavals of the 1960s and ’70s. A third is the moment we’re living through now. Each of those periods saw scads of new species germinating in the cultic milieu, and each of them gave us cult scares.

If the sects that grow in the cultic milieu sometimes take an authoritarian form, so at times does the backlash against them. A decay in a society’s dominant institutions can produce what Inglehart calls an “authoritarian reflex.” His book lists two forms that reflex can take: xenophobia and the desire for a strongman. Both are on display in the MAGA right. But secular centrists are also capable of longing for old certainties and for the institutional power that protected them—of looking at those unfamiliar alternatives sprouting around us, fretting that we’ve entered a “post-truth era,” and calling for controls meant to herd everyone into the “common reality” they imagine we shared in the past.

That past never existed. The human race has always lived in a patchwork of sometimes drastically different mental worlds. But as those worlds mix and multiply, the old authorities become more anxious; and anxious people often project their fears onto an external enemy with a name. One of those names is that traditional American demon, the cult.

from Latest – Reason.com https://ift.tt/2SL438m

via IFTTT