“The Unthinkable Has Become Possible” – Germany Faces A Political Revolution In 4 Weeks

In a scenario that nobody could have predicted one year ago, Germany is facing a political revolution in less than a month, on September 26, when the country holds its Federal Elections and where the dynastic CDU/CSU appears on the edge of not just losing, but suffering its worst ever election result.

But first, let’s back up one week to August 21, which was supposed to be the turning point for Germany’s ruling Christian Democrats – the day Angela Merkel threw her weight behind the beleaguered party leader Armin Laschet and turned around his flagging electoral fortunes. Instead, as the Financial Times notes, “it was a day of reckoning.”

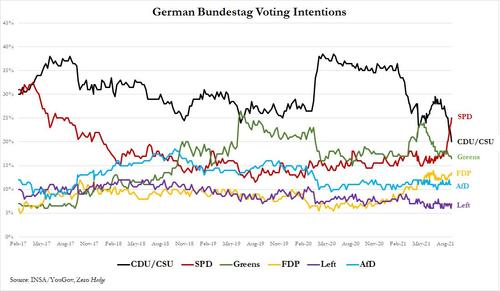

A poll that Saturday evening showed that support for the party had slumped to 22%, level with the left-of-centre Social Democrats. Data released earlier today from INSA, suggests the SPD had even pulled ahead significantly, rising to 25% while the CDU/CSU has collapsed to just 20%. This means that if its luck doesn’t turn before polling day on September 26, the CDU could be heading for the worst election result in its history.

So fast forward to today when with less than a month of campaigning to go, the FT reports of a sense of panic spreading through CDU ranks. “The mood is just abysmal,” says one conservative backbencher. “Are we all going to lose our seats now?”

‘All’ maybe not… but many, yes because a party that has ruled Germany for 50 of the past 70 years and began to see the chancellery as its natural birthright is now facing the real prospect of being booted out of power. It would, as the FT puts, it, “be a crushing humiliation for one of Europe’s most successful conservative parties.”

The reason for the party’s dismal plight, according to CDU MPs, advisers and strategists, is clear – its candidate for chancellor, and Angela Merkel’s handpicked successor, Armin Laschet. His approval ratings, never high to begin with, suffered a big drop in July when he was caught laughing on camera while visiting areas devastated by floods. They have never recovered.

Indeed, critics wonder aloud how the CDU, a party with “an unerring instinct for power and a reputation for iron discipline,” could have fielded such a weak candidate in the first place. “CDU people in my constituency say whatever you do, don’t send us any posters with Laschet’s face on them,” said another backbencher. “The fact is he’s a liability, rather than an asset, to our campaign.”

Some believe it was a fatal mistake to nominate Laschet ahead of his rival Markus Söder, leader of the CDU’s Bavarian sister party, the Christian Social Union, a much more popular politician. “The majority of CDU voters . . . did not want Laschet as chancellor-candidate,” Manfred Güllner, head of pollster Forsa, told the FT.

But there is another view: that the CDU’s decline has less to do with Laschet than with the end of the Merkel era. “All the time Merkel was in charge, the CDU was defined by its leader, not its policies,” says Jens Zimmermann, an SPD MP. “And now that she’s finally going, there’s this vacuum it just can’t fill — a void where the policies should be. People just don’t know why they should vote Christian Democrat.”

But one doesn’t have to go back a year to observe the dramatic shift in sentiment: just a few weeks ago, the common wisdom in Berlin was that the CDU/CSU would win the election and form a coalition with the Greens — the first such “black-green” alliance in German history. But the latest polls point to a much messier outcome according to many: an inconclusive election result with no clear winner and a plethora of different potential coalitions. “We will never have had so many government options in Germany’s postwar history,” says Güllner.

The mess is boosting the chances of a new, left-leaning alliance emerging, under a Social Democrat chancellor — the current finance minister Olaf Scholz. A party that has, for the past eight years served as junior partner in a Merkel-led “grand coalition” may be on the point of capturing the chancellery for the first time in 16 years.

“In the past, people used to smile indulgently when Scholz said he would be Germany’s next chancellor,” Niels Annen, a senior SPD MP and close Scholz ally, told the FT. “But an SPD-led government is no longer a fantasy. It’s a realistic proposition.”

What would such a political avalanche mean in practice? Analysts are confused by the inherent cross-currents in the various platforms – the SPD and Greens want to introduce a wealth tax and massively increase state investments, but they would probably need a third party in their coalition – the pro-business Free Democrats, who want tax cuts and balanced budgets. Such a “traffic light” coalition – as it is called due to the green, yellow, red colors of the constituent parties – could just end up cancelling each other out, and achieving little according to the FT.

No matter the final outcome, it will signal the end of an era. “The idea that the CDU might not win the most seats and not form the next government used to be unthinkable,” says Andreas Rödder, a historian at Mainz University. “Now the unthinkable has suddenly become possible”, a possibility made explicit by the latest Insa poll for Bild which showed extending support for the SPD which blimed one percentage point to 25%, pulling further ahead of Merkel’s conservative bloc which loses one point and falls to 20%; the Green party lost 0.5 points to 16.5%, the business-friendly FDP rose +0.5 points at 13.5%, while the far-right AfD was unchanged at 11% and the Left Party gained one point to 7%.

* * *

Even before the latest polls, it was clear that this would be an election like no other. Merkel said as much at the CDU/CSU event in Berlin’s Tempodrom, when she endorsed Laschet: for the first time in Germany’s postwar history, an incumbent chancellor was not running for re-election. “The cards are being reshuffled,” she said.

That has meant more scrutiny of the three individuals running to succeed her than of their policies or manifestos. As the FT details, “mone of them are as instantly recognizable and widely admired as Merkel herself. And for two of them, the media spotlight has been particularly harsh: Annalena Baerbock, the 40-year-old Green leader, spent weeks fighting off accusations of plagiarism and of embellishing her CV: meanwhile Laschet, prime minister of the large industrial state of North Rhine-Westphalia, has found himself attacked and ridiculed at every turn.”

Frequently, he has only himself to blame. At a recent campaign appearance in the western city of Wiesbaden, he repeatedly referred to the local CDU MP as Ingbert Jung. A murmur went through the crowd. “His name’s Ingmar,” one person shouted.

“It’s sheer sloppiness — just atrocious,” says a CDU politician who witnessed the incident. “Jung probably wanted to die of shame.”

Sometimes, the criticism seemed gratuitous. He has been ripped apart on social media for not wearing rubber boots on trips to flood-affected areas, eating an ice cream on the campaign trail and daring to mention hydrogen technology in a chat with Elon Musk. “Laschet is in this negative spiral now, where everything he does is just slammed,” says Rödder. “And once you’re in it, it’s very hard to get out.”

In contrast, Scholz, who as deputy chancellor steered Germany’s public finances deftly through the pandemic, has not put a foot wrong. “It seems as if voters have already made up their minds about the three candidates,” says one person close to the CDU. “They see Laschet as embarrassing, Baerbock as a fraud and Scholz as the only serious, solid one.”

Scholz’s message to voters has been simple: he is the natural successor to Merkel, a politician who continues to enjoy sky-high approval ratings even after 16 years in power. It is a bold claim: he is, after all, from a rival party. But it is one that SPD strategists have been quietly pushing for months, and the latest polls suggest it is working.

The similarities are, indeed, striking. Like Merkel, Scholz is dispassionate, pragmatic and no great orator: his delivery is so robotic he’s been nicknamed the “Scholz-o-mat”. Asked in a recent interview if he lacked emotion he replied that he was “running for the job of chancellor, not circus director”. Yet like Merkel he is widely seen as dependable and trustworthy.

So transfixed is the potential future premier with piggybacking on Merkel’s halo that Scholz himself shamelessly underscored the similarities by appearing on the cover of the Süddeutsche Zeitung magazine this month with his fingers and thumbs touching to form the Merkel “diamond”, the chancellor’s signature gesture.

“It was sensational, because it finally put the cliché to bed that he doesn’t have a sense of humour,” says Zimmermann.

In a recent FT interview, Scholz tacitly acknowledged that he was trying to target Merkel voters. “A lot of people would see me as the best bet, because I have more government experience than any of the other candidates,” he said. “But it’s much more than that: I also have a clear idea of how to ensure Germany’s prosperity and also more respect in society,” he added.

As the FT explains, the theme of “respect” is at the heart of the SPD campaign, which is built on a battery of simple messages: a €12 per hour minimum wage, more affordable housing and stable pensions.

The party has been unusually united, avoiding the open bickering between left-wingers and centrists that blighted previous campaigns. And because it nominated its candidate for chancellor much earlier than its rivals — more than a year ago — “we were able to create a customized campaign exactly tailored to Scholz”, says Zimmermann.

Still, it’s not all smooth sailing, and things could still turn against Scholz, however. Uncomfortable questions have been raised over his role in the two big financial scandals that have rocked Germany in recent years — the fall of digital payments company Wirecard and the cum-ex tax fraud, a controversial set of share trades that robbed the German exchequer of billions of euros in revenue.

Separately, the Financial Times also notes that SPD critics also increasingly ask whether Scholz really represents his party. A centrist, he lost the 2019 contest for the leadership of the SPD to a pair of leftwingers, Saskia Esken and Norbert Walter-Borjans, who have kept quiet during the campaign but still have a massive fan base in the party.

“People don’t really know Scholz at all — he’s just a blank canvas they’re projecting all their wishes and desires on to,” says Manuel Hagel, a senior CDU official. “But it’s only a matter of time before he’s subjected to exactly the same scrutiny that Baerbock and Laschet have had to endure.”

For the moment, however, the polls are clearly going Scholz’s way, and the nervousness in the conservatives’ camp is growing. That was clear when Söder followed Merkel on to the stage of the Tempodrom earlier this month. The CDU/CSU is, he said, facing its hardest election campaign since 1998, the year veteran chancellor Helmut Kohl was kicked out of office by the SPD and Greens.

“Let’s be honest for a moment — it’s tight,” he said. The Christian Democrats had for months been speculating about which parties they could form coalitions with. “But the question now isn’t how we should govern, but whether we will govern at all,” he added.

It’s been a painful campaign for Söder. He saw his poll ratings soar during the pandemic, when he emerged as one of Germany’s most effective and decisive crisis managers. Laschet, in contrast, was seen as a poor communicator, unsure what line to take. “His zigzag course really depressed his approval ratings,” says Forsa’s Güllner. Yet in the end, the CDU chose Laschet, the candidate of the party hierarchy, rather than Söder, the favorite of MPs and the party base.

From the start, Laschet’s campaign for chancellor was faulted for its incoherence and its lack of eye-catching policies. He started off promising voters a “decade of modernisation”. “But then people said — well why didn’t you use your past 16 years in power to modernize the country?” says the person close to the CDU. In recent days the slogan has been quietly dropped.

That encapsulates Laschet’s problem: he needs to be Merkel’s natural heir while also signalling a fresh start. “He can’t portray himself as some kind of superhero who will save everyone from the government — because the government is the CDU,” says one person close to him.

Laschet could still save the day by setting out clearly what parts of the Merkel legacy he would preserve and what he would do differently. Some think he could also improve the CDU’s chances by unveiling his dream team — the members of a putative Laschet-led cabinet. “If your top candidate is not performing, you should show the full spectrum of the party,” says the backbencher. “He isn’t doing that.”

Critics, however, say the CDU/CSU’s problem is its fundamental lack of new ideas. “It’s a Potemkin village,” says Oliver Krischer, a senior Green MP. “There’s nothing left behind the facade.”

As the concerns grow, some Christian Democrats are pushing for increasingly desperate measures. In a poll published on August 25, 70% of CDU/CSU voters said they wanted Laschet to step aside in favor of Söder, who remains highly popular among the CDU’s rank and file: “A lot of members are still really peeved about the way Söder was sidelined,” says one CDU MP. He says some local party volunteers had warned him at the time that they would not campaign for Laschet if he was chosen as candidate — “and they have kept their word”.

Then there is history: CDU officials say it would be wrong to underestimate Laschet, a politician renowned for his resilience. “Four weeks before the 2017 elections in North Rhine-Westphalia, the CDU was six points behind the SPD, but we still won,” says Hagel. “It shows you can win when you really fight.”

Further adding to his chances of a last-minute miracle, is that many German voters remain undecided. And CDU strategists point to polls that show 30% of the German voting public is essentially conservative — a constituency that could swing the CDU’s way on polling day. “We can still turn things around,” says Hagel. “All elections are decided in the last three weeks of campaigning.” But privately, other Christian Democrats are less optimistic. “The fact is, we weren’t able to come up with a candidate who could really convince voters,” says one backbencher. “And now we’re being punished for it.”

* * *

Laschet’s chances for a rebound took a turn lower on Sunday night when in the first of three TV debates in the campaign leading up to Germany’s federal election on 26 September, Olaf Scholz scored what may be a devastating victory in his race to succeed Angela Markel.

While all three debate participants – Laschet, Scholz and Baerbock – essentially delivered, there was only one clear winner according to the New Stateman: Scholz, who triumphed in a snap poll by Forsa. To the question “Who do you tend to trust to lead the country?” fully 47% named the SPD candidate, with 24% for Laschet and 20% for Baerbock. The question of who won the debate itself was slightly narrower but still clear: 36% called it for Scholz, 30% for Baerbock and just 25% for Laschet. Narrowest was the question of which seemed most sympathetic: here Scholz (38%) was only just ahead of Baerbock (37%), with Laschet trailing far behind on a dismal 22%.

Today’s Bild, a conservative tabloid traditionally close to the CDU/CSU and Germany’s most-read newspaper, is emphatic: “Clear victory for Scholz in TV” runs its front-page headline.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 08/31/2021 – 02:45

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3juXdir Tyler Durden