Free Trades – A World Without Payment-For-Order-Flow

Authored by Marc Rubinstein via ‘Net Interest’,

Anyone who’s seen the Apple TV show Ted Lasso will be well versed in the differences between American and British behaviours. Tea and biscuits, football draws, the underhand nature of the British press – it’s all in there.

One thing that’s not in there, though, is financial services. Which is a shame because there are lots of differences between financial practices in the US and the UK. One of them is the role of payment for order flow in retail stock trading. Payment for order flow underpins the business model of Robinhood, an American company named after a British legend. Yet in the UK, it is banned. If Ted were to pull out his phone to buy some UK-listed shares, the way his order is routed to the market would be very different to anything he may be used to back home.

It’s a topic worth exploring because European regulators are in the process of banning payment for order flow too and US regulators may very well follow. Against this backdrop, new business models are emerging.

What is Payment for Order Flow?

Payment for Order Flow (PFOF) is a fee that a broker receives in return for routing trades to specific exchanges or dealers for execution. Hit confirm on the purchase of a few shares of Citigroup in your trading app [this is not investment advice] and rather than sending it to the stock exchange to be executed, your broker will typically send it to a wholesale market maker.

There are about eight of these market makers active in the US. The largest is Citadel Securities, then there’s Virtu, G1 Execution, Goldman Sachs, Jane Street, Two Sigma Securities, UBS Securities and Wolverine. Their pitch is that they can deliver a better price for the end customer than if the trade was routed direct to an exchange. That’s because as well as trafficking between exchanges, these market makers tap into so-called dark pools of liquidity. And increasingly, that’s where the action is. These days, more shares can be executed in private, dark venues than on public exchanges. In the case of some stocks, where retail participation is high, 60-70% of trading can occur in the dark.

One such dark venue is the market maker’s own balance sheet. Given their scale, market makers are often able to match up trades from within their flow. There are around 200 retail brokers in the US but once their orders are aggregated among the eight wholesalers, there is ample opportunity for matching. Retail orders tend to be small, dispersed and uninformed, so the chances that a Citigroup sell order comes in on the same day as a Citigroup buy order are quite high. Virtu, one of the largest market makers, reckons that around 60% of the retail volume it handles is dealt with internally.

The advantage for the customer is a better price. Brokers are required to offer the best available price, but only with reference to what’s posted on public exchanges. For Citigroup, that price may be $67.20 to sell or $67.40 to buy. Scour these dark pools and better prices emerge. If the market maker itself can execute the trade at $67.25 for the seller and $67.35 for the buyer, both are better off and there’s still something left in the middle for the market maker.

In aggregate, market makers reckon they delivered $3.6 billion of price improvement to retail investors last year. Virtu argues that if you adjust for order size, price improvement is even higher and on that metric they alone delivered $3 billion of improvement.

In order to attract flow, market makers offer payments. This is where the payment for order flow comes in. Some brokers – Fidelity, for example – don’t take it, but many do. In particular, several have crafted a business model around it, using payment for order flow to subsidise the cost of trades. Over the full year 2020, Robinhood earned $691 million in payments for order flow, representing 72% of its total revenue.

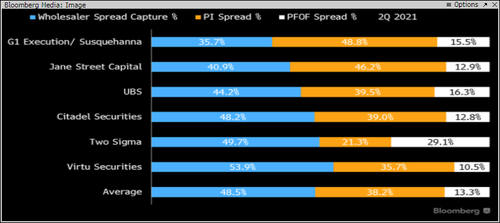

Payment for order flow allows the broker to share in any value captured by channeling orders through wholesalers, along with the wholesaler and the end customer (through price improvement). Bloomberg estimates that for every $100 of value captured, around $49 stays with the wholesaler, $13 goes to the broker and $38 ends up with the customer.

Neat as all this sounds, it is highly controversial. There’s a reason they don’t allow it in the UK (or Canada). The issue is the potential conflict of interest it presents. The European Securities and Markets Authority sounds the alarm: “PFOF causes a clear conflict of interest between the firm and its clients, because it incentivises the firm to choose the third party offering the highest payment, rather than the best possible outcome for its clients when executing their orders.”

Such conflicts were exposed at Robinhood last December, leading to the firm being fined $65 million. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) discovered that Robinhood had locked in unusually high payment for order flow rates but wasn’t getting much price improvement on customer orders. According to the SEC, inferior trade prices deprived customers of $34.1 million in the 30 months up to June 2019, even after taking into account the savings from not paying a commission.

The controversy around payment for order flow is nothing new, it’s just that entire business models have been built while it’s been simmering. Twenty years ago, Bernie Madoff defended the practice – not someone you really want fighting your corner.

“No one tells a firm how they can advertise. If I want to hire salesmen to generate order flow, no one is going to object. I don’t have them. So if I want to use Fidelity’s salesmen and pay part of my trading profits in the form of a rebate, why shouldn’t I be allowed to do it? It was characterized as this bribe and kickback and something sinister, which was very easy to do. But if your girlfriend goes to buy stockings at a supermarket, the racks that display those stockings are usually paid for by the company that manufactured the stockings. Order flow is an issue that attracted a lot of attention but is grossly overrated.”

In the UK, financial regulators classified payment for order flow as an inducement at odds with best execution back in 2012 and banned it just as it was beginning to take off. A study has since shown that the ban did not have a detrimental effect on pricing, with customers benefiting from a more competitive market for retail orders.

This week, Europe has followed suit. The European Commission updated a broad set of rules around capital markets, including amendments “to stop the controversial practice of trading operators offering incentives to brokers for directing client orders to them, regardless of whether or not doing so is in their clients’ best interests (‘payment for order flows’).”

For new brokers like Trade Republic in Germany – valued in a recent funding round at $5 billion – this is potentially very damaging. Payment for order flow accounts for around half their revenue. Another broker, flatexDEGIRO has disclosed that payment for order flow makes up only 3% of its revenues, leaving it better placed.

Nowhere is payment for order flow more embedded though than in the US. Yet here, too, there are rumblings that it may be banned. The newly appointed Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission has put a full ban “on the table.” Interviewed by my close namesake David Rubenstein recently, he added:

“You’re supposed to get best execution out of your broker and is that happening when…a few wholesalers are buying the order flow and a lot of that’s getting concentrated around a few wholesalers?”

A World Without Payment for Order Flow

A ban on payment for order flow would leave brokers with two choices:

They could reverse into the market making business themselves. Historically, retail brokers including E*Trade, Charles Schwab and Interactive Brokers did operate such businesses. But the rise of electronic and high frequency trading narrowed bid/offer spreads, convincing them to sell to scale providers. Charles Schwab sold its execution services business to UBS in 2004, E*Trade sold to Susquehanna in early 2014, and Interactive Brokers sold to Two Sigma in 2017.

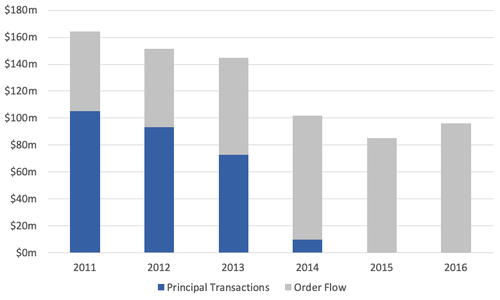

When it sold to Susquehanna, E*Trade argued it wouldn’t suffer a decline in profit because new sources of payment for order flow would offset lost trading profits. Payment for order flow is a higher margin activity than market making, so E*Trade may have been right at the profit level. But on the revenue line, the firm did lose out. In the three years prior to the sale, E*Trade earned an average of $90 million a year from trading, of which around 60% was internal flows; payment for order flow increased by only around $30 million a year subsequent to the sale.

Source: E*Trade financial reports

If payment for order flow disappears, a reverse back into trading could make sense for E*Trade, especially now it has access to a better trading platform as part of Morgan Stanley (which bought it in 2020). More broadly, larger brokers have a particular advantage at being able to internalise trades. Robinhood alone does more retail equity trading than any market maker outside the big two (Citadel Securities and Virtu).

A second option is to seek out alternative revenue sources. This is where the UK experience comes in. In 2016, a new broker was founded in the UK, Freetrade. The firm set out to offer Robinhood-style trading without recourse to payment for order flow: “We do not receive financial or non-financial benefit from any trade execution venues or counterparties in return for sending our customers’ orders to them (sometimes known as ‘payment for order flow’).”

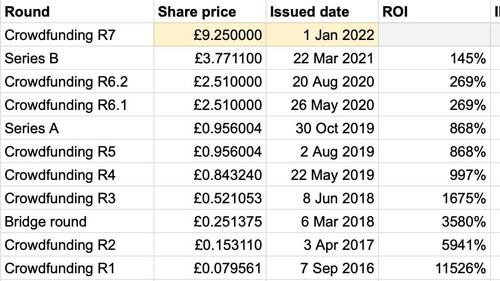

Freetrade now has around 600,000 funded accounts in the UK, of which 475,000 have been active in the last thirty days. In the third quarter of this year, it processed 2.6 million trades. Like Robinhood, it has an engaged user base with a similar average age (34). Unlike Robinhood, it has used that customer base to fund its growth. Following an original crowdfunding raise in 2016 (for £170,000), the company has launched seven further rounds. This week, Freetrade launched its latest round, valuing the company at £650 million. Within a few hours, the company raised £3.7 million from existing investors and a further £1.3 million from others who signed up for early access. After four hours, the company had raised £8 million from over 6,000 investors.

Unusually, Freetrade sometimes offers investors secondary trading opportunities, allowing them to lock in profits. How much of that gets recycled back into the platform though is unknown. The company has over £1 billion in assets on its platform, the two largest cohorts being the pre-Dec 2019 cohort and the first quarter 2021 cohort.

Freetrade funding rounds

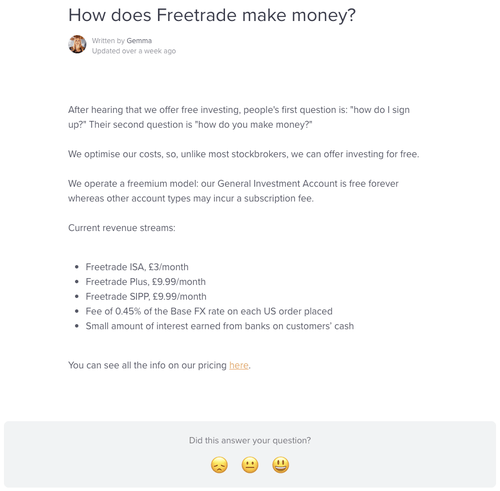

So how does Freetrade make money?

Here’s how the company puts it:

I’m not too sure how optimising costs enables free investing, but looking beyond that, Freetrade makes money from subscriptions with upside from FX and interest income.

In 2020, the company made £3 million revenue. For 2021, they are forecasting £15 million, less than original projections because of a slower rollout into Europe. Leaving 2021, they are doing £2 million in revenue a month, so that’s around £40 per funded account on an annualised basis. The projection for 2022 is £50 million of revenue. Gross margins are around 90% but staff and overhead costs are expected to continue to consume revenues until 2023.

The core subscription model creates an alignment with customers – Freetrade isn’t incentivised to get them to trade more. Which is a good thing! Its customers trade an average 17x per year compared with Robinhood’s 25x (in equities) as at the third quarter. It’s also a more resilient model – revenues won’t collapse with trading velocity, although they are subject to churn. With higher interest rates, Freetrade will be able to secure a larger stream of interest income on uninvested cash.

Freetrade remains very small next to the giants in the industry like Robinhood. But it’s an interesting model to watch, particularly as payment for order flow comes under pressure. The model may be foreign to Ted Lasso but, as Rebecca tells him, “every disadvantage has its advantage.”

* * *

This is a free version of Net Interest, my newsletter on financial sector themes. For additional content and supplementary features, please consider signing up as a paid subscriber.

Tyler Durden

Sun, 11/28/2021 – 16:40

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/3lg6Y4w Tyler Durden