“Many Unholy Trinities” – ECB Failure Is (Almost) Guaranteed

By Elwin de Groot, head of macro strategy at Rabobank

After last week’s recession fear-driven bounce-back in bonds (especially those at the shorter maturity section of the curve), markets took a breather on Monday as the US were closed for Independence Day. The European 2-year swap rate (which declined by a whopping 80bp in the last two weeks of June), recovered by more than 10bp yesterday. Arguably that was also driven by hawkish comments from ECB officials, such as Bank of Slovenia Governor Vasle, who warned that there will “likely be more rate hikes […] after September”. The RBA’s second consecutive 50bp hike this morning – albeit in line with the market’s expectations – served as another reminder that short-term rates are on a (steep) upward slope, globally.

Meanwhile, the US and China are in talks over a roll-back of tariffs imposed by the former Trump administration. It is our understanding that Treasury Secretary Yellen is a proponent of such a reversal, but that there is no unity on this issue in the Biden team. US Trade Representative Katherine Tai, for example, sees the tariffs as useful leverage in broader discussions with China (although sceptics will argue that the tariffs have done little to rebalance the trade relation between the two countries). The downward impact this would have on inflation is likely to be quite modest according to many analysts. Still, if such a decision were to coincide with the start of a downward trajectory in inflation (for entirely different reasons, such as ‘peak’ commodity prices), President Biden –who has also expressed great concern over cost of living issues for US households– may spin it as a vote-winner as the November mid-term elections are drawing closer.

Overnight, we’ve seen more ‘positive’ news from China, as the Caixin composite PMI survey for June rebounded strongly (55.3 from 42.2 in May) following the relaxation of lockdown measures in big cities such as Shanghai and Beijing. However with new reports of flare-ups of Covid-19 in the eastern province of Anhui as well as the broader Yangtze Delta region, which is a key economic hub, the pick-up in activity may well prove to be short-lived.

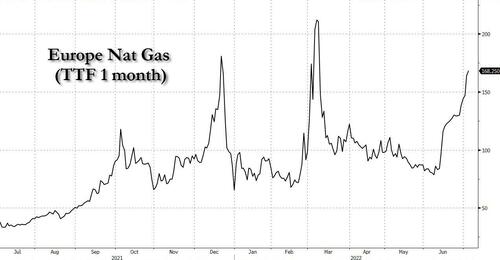

Indeed, we would argue that it is far too soon to throw recession fears out of the window. From the European side, we were also kindly reminded of that over the weekend by German Federation of Trade Unions (DGB) head Yasmin Fahini, who warned in an interview with Bild that “entire industries are in danger of permanently collapsing: aluminum, glass, the chemical industry” as a result of the current gas bottle necks. The 60% decline in Russian gas deliveries through the German Nordstream-1 pipeline system has pushed European gas prices to levels not seen since the first weeks of the Russian invasion in Ukraine. The TTF 1-month contract rose above EUR160/MWh yesterday, the highest level since 8 March. Rising import prices were also the main culprit behind Germany’s first monthly trade deficit (a EUR 1bn net loss) in May since 1991, as export activity is being hampered by Chinese lockdowns, slowing global demand and ongoing supply chain issues whilst import prices (of energy in particular) are going through the roof.

Germany has already switched to phase 2 of its national gas emergency plan, just one step shy from taking complete control over the allocation of natural gas. Its previously mothballed coal-powered electricity plants are being fired up again and the government is still in talks with Uniper, its biggest gas importer, on what support measures it will provide. According to Germany’s Spiegel magazine, the government is working on legal basis to support gas supply companies with measures that could include the acquisition of shares and/or grant loans or guarantees. The Lufthansa bailout is seen as a blueprint for such measures. Bloomberg reports this morning that the potential bailout package could be as much as EUR 9bn.

But Chancellor Scholz acknowledged yesterday that the country is facing a “historic challenge” and that the rising costs of living could have “explosive” effects on German society, as it also drives a further wedge between the rich and the poor. Arguably, the Chancellor himself is facing one of those Unholy (or Impossible) Trinities: he cannot prevent social unrest, if he wants to have lower inflation and wants to prevent a recession at the same time. One could argue that simultaneously achieving the latter two objectives are already a daunting task in itself, let alone doing so without causing tensions between those in work and those enjoying their pension, or between the providers of capital and the providers of labour.

So he’d better leave the prevention of inflation in the safe hands of the ECB, right? Oh, hang on, that other institution is actually dealing with an Unholy (or Impossible) Trinity itself. In fact, we would argue, one that is of its own making.

Before you start googling, the “Impossible trinity” concept dates back to the research by international economists Robert Mundell and John Fleming. The central tenet of their reasoning is that it is impossible to have all three of the following at the same time:

- i) independent monetary policy (i.e. full control of your money supply),

- ii) a fixed/stable exchange rate and

- iii) the free movement of capital.

The prime example often used to explain the trinity is the situation where the central bank choses its own monetary policy amidst free capital flows. Under that regime – which basically is the regime under which many developed-markets central banks are currently operating – the central bank cannot control the exchange rate. For if it wants to fix the exchange rate it would have to use its FX reserves to steer the exchange rate. Since these reserves are limited it cannot support its currency indefinitely should it want to maintain an interest rate that is below the ‘global’ interest rate. Should it want to maintain an interest rate that is above the global level, it would likely see considerable capital inflows and the only way to stabilize the exchange rate is to purchase the influx of foreign currency by printing more of its own money, thus raising the money supply and stimulating growth and inflation.

But, we hear you thinking: things are absolutely fine for the ECB, right? Because the “exchange rate is not a policy target”. So no problem there. However, we are actually thinking about yet another Impossible Trinity that is currently playing havoc with the ECB. Over the weekend, the FT reported that the ECB is in discussion over whether and how it could prevent banks from making “multibillion euro” windfall profits from the cheap loans that the ECB has provided them during the pandemic. The basic idea here is that many banks have met their TLTRO targets and therefore borrow at the average deposit facility rate over the entire life of the loan. Since this average rises much more slowly than the actual deposit facility rate when the ECB hikes rates later this month, this effectively offers banks a free lunch.

We asked ourselves: this is not a new issue and the ECB could have seen this coming when it devised the policy. So why and why now? Well, one explanation could be that the ECB has been surprised by the relative low amount of TLTRO repayments by banks so far. But a more interesting explanation – in this regard – is that, in the process of designing its Anti Fragmentation Tool, the ECB may suddenly be realising that it has to give up control of the size of its balance sheet (or better: the monetary base), if it wants to maintain control over interest rates and spreads and prevent fragmentation at the same time.

A thought experiment helps explain the issue. Let’s assume concerns over Italian spreads force the ECB to buy more Italian bonds. And let’s assume that in order to fully sterilize the impact on the monetary base, the ECB decides to sterilize by mopping up liquidity through ‘weekly deposits’ (at a slight premium over de deposit facility rate). This, however, implies that the monetary base would effectively continue to expand, posing long-term risks to inflation. Alternatively, should the ECB decide to raise its reserve requirements by the same amount as it has pumped into Italian bonds, the increase in those requirements would likely pose a problem for those banks already low on excess reserves and who would not see a commensurate increase in their reserves. As a consequence, the fragmentation issue may not be solved. And if the central bank were to issue securities with a long maturity, this would probably raise long-term interest rates (as they would compete with other core bonds). So while that may contain spreads, it would not be able to contain long-term yield levels.

So the basic conclusion here is that, with so many goals to achieve, the ECB risks becoming all tied up in its own instruments. Failure is almost guaranteed. It just has to choose where it accepts such failure.

Tyler Durden

Tue, 07/05/2022 – 09:52

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/DGNbUCK Tyler Durden