America’s Freight Railroads Are Incredibly Chaotic Right Now

By Rachel Premack of FreightWaves

Jason Doering has seen a lot during his 18 years at Union Pacific Railroad. But what’s happening with the current hiring class at UP is unprecedented. “They’re dropping like flies,” Doering said. “I mean, I’ve never seen it.”

A railroad engineer or conductor typically earns a six-figure salary, retires with a pension and enjoys union benefits. They don’t need a college degree; the monthslong training is provided on the job. It’s the kind of career that ought to be popular — but Doering said trainees and longtimers alike are getting burned out. It used to be a job with eight- or nine-hour shifts and plenty of time at home. Now, Doering says railroading demands too much time away from one’s family and workdays that last up to 19 hours, combining 12-hour shifts with hours of waiting around for transportation or relief crews.

Union Pacific is struggling to find railroad crews after years of slashing headcounts. The $22 billion railroader had 30,100 employees during the first three months of 2022, according to its latest earnings report. Five years prior, the company had nearly 12,000 more workers. (A representative from Union Pacific declined to provide a comment for this article, as the company is reporting its second-quarter earnings later this month. The rep did share a company blog on the importance of supply chain fluidity and cooperation.)

This employment issue isn’t unique to Union Pacific. America’s railways are in an unusually chaotic state as Class I lines struggle to find employees. That’s led to congestion that analysts say is even worse than 2021, which saw some of the biggest rail traffic in history. Now, a strike of 115,000 rail workers could happen as soon as next week.

“We’re spending more time at home-away terminals than we are at home,” Doering said. Doering is also the Nevada legislative director for SMART Transportation Division, a labor union of train, airline and other transportation workers. “So the attitudes out here, I think, are warranted. Morale is at an all-time low.”

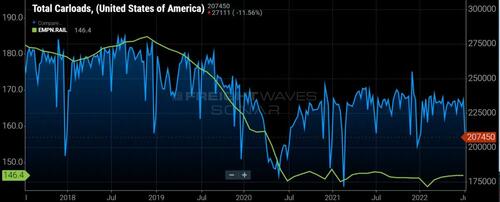

Longtime rail analyst Tony Hatch said there’s something unusual going on with rail headcounts right now. Typically, crews and carloads move in lockstep, with railroaders able to hire up or down in times of increased or decreased traffic. Now, those companies haven’t been able to keep up. Carloads have steadily increased since mid-2020, but employment hasn’t matched that.

“There was a big, ahistorical break in the tandem relationship between rail crews and volume,” Hatch said.

Outside being stuck behind a miles-long behemoth, one does not think often about the importance of the humble train. It isn’t as ubiquitous as the truck, as swift as the cargo plane or as cosmopolitan as the container ship. It may seem even a bit antiquated. Indeed, the cargoes on railcars aren’t usually goods exposed to the consumer — think gravel, grain, coal and chemicals. These are crucial components for our larger economy. Gravel becomes the foundations of our homes and roadways, grain our food (and our food’s food), coal our electricity and chemicals the basis of many everyday products.

So, while you may not have been keeping up to date with rail congestion, industrial bigwigs and lawmakers alike are furious. The coal industry is slamming rail for the “meltdown” in service capacity and grain shippers said they had to spend $100 million more in shipping costs to get their product moved amid poor rail service. The Port of Los Angeles is taking to the press to demand rail move those gosh darn containers away, saying that railroaders could cause a “nationwide logjam” with the unmoved containers sitting around. Members of the federal government’s Surface Transportation Board recently demanded answers from railroad executives in a May two-day hearing, but tensions seemed to have only worsened since then.

Even more exhausted are the rail workers themselves. Rail unions have been negotiating with their employers since January 2020, with a “dead end” in negotiations reported two years later. Now, President Joe Biden is being charged with appointing a “Presidential Emergency Board” to nail down a new contract. If he doesn’t do so by Monday, railroad crews could legally have their first nationwide strike since 1992. Such a strike, according to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, would be “disastrous.”

“They’ve cut labor below the bone, really,” STB Chairman Marty Oberman told the House Transportation Committee in May. “In order to make up for the shortage of labor, they are overworking and abusing the workforces they have.”

Meanwhile, the Association of American Railroads said in a May statement that the rail companies it represents were committed to hiring more and to addressing rail service issues.

“The rail industry understands its critical role in serving the U.S. economy and is confident in its abilities to work alongside customers to remedy service issues moving forward,” AAR President and CEO Ian Jefferies said in the statement.

It’s a chaotic situation, and the roots predate COVID. Here’s what happened:

Two sneaky tricks railroads love — and shippers hate!

Let me tell you the hottest rail trend of the 2010s: precision-scheduled railroading. As The Wall Street Journal’s Paul Ziobro explained in a 2019 story, PSR means that railroads have set times for when they pick up cargo from their customers, not unlike a commercial airline. Before, railroads would wait for the cargo.

There are endless implications that come from this system, some of which my colleague Mike Baudendistel delved into in this 2020 article. PSR allowed railroads to reduce capital budgets, slash headcount and consolidate with glee. But its biggest boon to the railroaders was how much it boosted their cred on Wall Street, creating billions in shareholder value.

“The railroad stocks have greatly outperformed the broader market in the past 15 years, which took place despite the major deterioration of coal volume, the railroads’ historical business,” Baudendistel wrote.

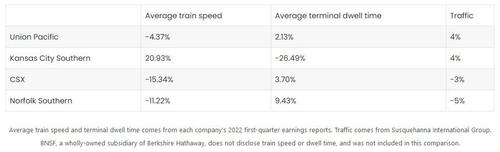

There are serious service issues with PSR, though. When the tactic was first implemented at CSX Transportation, dwell time at some terminals increased by as much as 26 hours, according to another 2019 WSJ piece by Ziobro. Trips that would take a few days stretched out to more than two weeks — a struggle for customers that relied on just-in-time supply chains.

We could go on all day about PSR, but I’m bringing it up today because the tactic allowed railroads to seriously slash headcounts.

The legacies of PSR have contributed to low employee numbers at the railroads today, said Todd Tranausky, vice president of rail and intermodal at forecasting firm FTR Transportation Intelligence.

Doering of Union Pacific noted another trend: super-long freight trains. This is a problem so grave that the federal government literally released a report on it in 2019, saying the trains had gotten so massive that pedestrians were climbing over them and emergency responders were unable to respond to incidents. However, long freight trains allowed railroaders to extract more profit from their equipment and workers, helping reach economies of scale.

MODES readers will know my, uh, feelings on overly large pieces of freight transport. But when it comes to railroad conductors and engineers, they really don’t like the mega-trains. One reason is that they’re simply slow, stretching the workdays longer and longer and grinding on morale. “When you’re going up a 20-mile hill going 9 or 10 miles an hour in the middle of the night, it gets on you,” Doering said.

Another reason is that it takes longer to fix them should a car or locomotive fail. Walking along miles of railcars, checking for broken knuckles or stuck brakes at each, isn’t my personal idea of a good time.

“That’s part of the lifestyle issue [in hiring],” Tranausky said. “How many people, when it’s 105 degrees outside or there’s a foot of snow, actually want to trudge a mile, two miles to find an issue, fix that issue, then go back down the road? There’s that lifestyle issue that’s exacerbated for how long the train is.”

COVID wiped out even more railroad payrolls

Rail giants, as you could guess, struggled during the early months of COVID. In April 2020, for example, rail carloads saw their biggest year-over-year drop since 1989 and intermodal loadings saw a decline not experienced since 2009.

Railroads were shedding employees from April until July 2020, when my colleague Joanna Marsh reported that crew headcount had finally begun to increase again. Still, there were 25% fewer crews than in 2019 and 28% fewer than 2018, according to data from the Surface Transportation Board.

The financial status of these firms was in question, which motivated them to furlough workers. “At least one Class I railroad held meetings to decide whether they had enough cash through the summer, if they had enough cash to pay the bills and could they stay in business,” Hatch said. “When they began to lay people off, much to the consternation today of the regulators and whatnot, you need some understanding that they did not know how long this would last.”

Railroaders struggled to re-hire those crews they furloughed. Many of them found work in construction or manufacturing, industries that allow workers to spend evenings and weekends at home, Tranausky said.

Unlike its siblings in trucking or ocean shipping, the railroad industry didn’t have a bonkers 2021 — but it survived. 2021 saw healthier volumes from the year before. They were still below 2019’s levels.

Railroad service is suffering even as volumes tick down

Service complaints from shippers, bureaucrats and lawmakers have gotten louder and louder in 2022. And data from the rail carriers shows that service has declined — train speeds have largely decreased from 2021 while terminal dwell time is up. But there’s an interesting wrench in this: Rail volume has actually decreased during that same period, according to data from Susquehanna International Group.

These railroads cut too much staff through the adoption of PSR and the pandemic. Rail employment today is down more than 20% since the beginning of 2019, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics — a “dramatic decline,” Tranausky said.

“It’s possible that the railroads furloughed too many and that they could have taken on more costs,” Hatch said. “I think one lesson out of this in the so-called just-in-case economy of the future will include railroads who will keep more safety stock [of labor].”

PSR helped railroaders boost margins and share prices, but its legacies could be contributing to today’s woes.

To address low staff, Berkshire Hathaway’s BNSF took one particularly unpopular approach. In February, BNSF began to penalize employees who took time off for fatigue, family emergencies or illness. Union officials said 700 rail crew left as a result of the policy. The $23.3 billion railroader nixed the policy in June.

Some issues are completely out of the railroads’ control. Most kinds of employers across the country are still struggling to find workers. Even finding shuttle drivers to take railroad crews to their terminal has been a struggle, from Doering’s observations. Recently, Union Pacific has put him in a taxi to go from Las Vegas to inland California. “We’re watching the little ticker up there in the cab go up to $400 or $500 for a trip,” Doering said.

Even in the best of times, it’s hard to find someone to sign up to be a railroad crew member. They have a similar lifestyle to, say, airline pilots, who must be away from their families for days at a time, living in hotels and manning massive, potentially dangerous pieces of equipment. Railroad crews are on call even during their home time.

They require months of training and after that need years or decades on the job to become truly masters of the rail. “There’s a learning curve,” Tranausky said. “[New crews are] not as efficient, not as productive as those higher-seniority crews.”

While Tranausky and Hatch said labor is the main driver of today’s congestion, one factor is totally outside the control of railroads. Unlike 2021, many warehouses are packed with inventory. Some insiders told FreightWaves that shippers are essentially using railcars as storage rather than moving the cargo into their own warehouse. That’s causing a shortage of chassis and increasing congestion — particularly in rail yards like Chicago.

“I think it’s easy to point fingers at a railroad and say the railroad’s creating the issue,” said Ashley Rittman, CEO of Valor Victoria, a railroad technology company. “Oftentimes I think the railroad is in a position (where) they have to be reactive to what environmental things happen to them, for them. If chassis are short or if customers are sitting on containers, their equipment is really held hostage from turning if everybody’s not working in harmony.”

… but the situation could get dire very quickly

Rail workers are governed by a slew of complex labor laws that dictate when they can legally strike. Currently, crews and their employers are in a mandated 30-day “cooling-off” period. That ends Monday, at which point crews could legally strike. President Biden is expected to appoint a Presidential Emergency Board to head off this strike.

Labor negotiators for the railroads told the Financial Times on Thursday that they offered workers a major pay increase and “benefits among the best in the nation.” A union negotiator countered to the FT that these offers had been “insulting.”

The tensions couldn’t come at a worst time for the so-called “pro-union” president, who is also pledging to help navigate tensions at the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. There, the union contract for some 22,000 workers just expired. Further adding to the chaos at America’s largest port complex is the recent Supreme Court decision to not hear a lawsuit concerning AB5, a bill that would dissolve the owner-operator model of trucking in the state of California. Hundreds of truck drivers there protested AB5 on Wednesday.

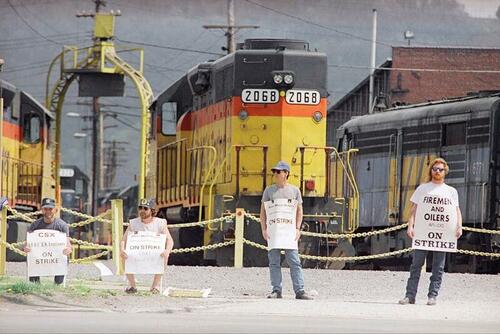

There hasn’t been a rail shutdown in the U.S. since 1992, when machinists at CSX Transportation went on strike. Their work stoppage actually shuttered all American rail operations, including passenger service, which operates on some freight rail. At the time, the White House estimated that the shutdown cost Americans $1 billion per day, or more than $2 billion in today’s dollars.

The 1992 strike, just two days long, was still incredibly disruptive. The Chamber of Commerce fears that a work stoppage this time around could be similarly crippling. “Any breakdown would be disastrous for U.S. consumers and the economy and potentially return us to the historic supply chain challenges during the depths of the pandemic,” wrote Suzanne P. Clark, CEO and president of the Chamber of Commerce, in a July 8 letter to the administration.

Meanwhile, Doering fears that even a robust contract couldn’t fix the low morale among his fellow railroad workers.

“Everybody goes to work and there’s nothing positive to talk about,” Doering said. “There are no positive things going on within the industry. You are forced to choose between your career and your life.”

Tyler Durden

Fri, 07/15/2022 – 10:32

via ZeroHedge News https://ift.tt/s81VXuB Tyler Durden