Authored by Charles Hugh Smith via substack,

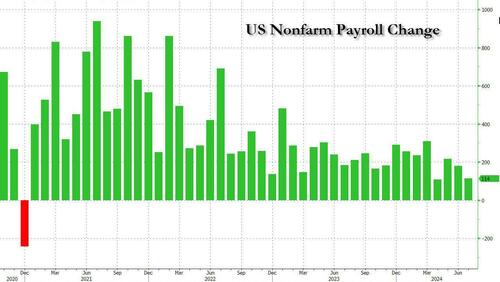

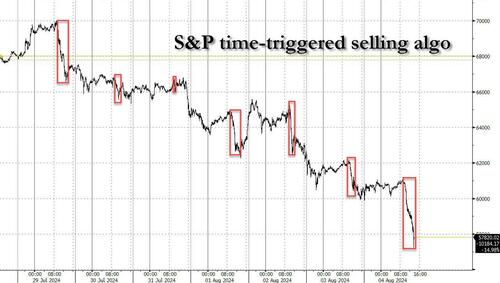

The global economy is slowing, and central banks and governments are deploying the usual stimulus tricks: 1) lowering interest rates to encourage more borrowing and spending, and 2) running large fiscal deficits so government spending fills the gap left by sagging private-sector spending.

But these usual stimulus tricks won’t work this time around, and the reason why is very simple: all the conditions that allowed these tricks to work were one-offs that are now done and gone. These one-offs weren’t policies that can be tweaked or reinvented; they were real-world conditions that are no longer present. They cannot be brought back with any amount of money or will.

Let’s start with China.

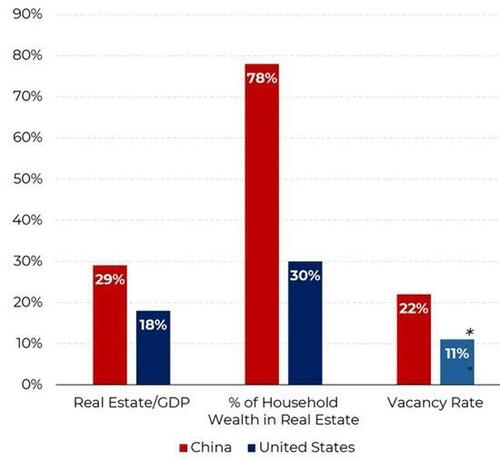

China bailed the world out of the last three recessions triggered by credit-asset bubbles popping: the Asian Contagion of 1997-98, the dot-com bubble and pop of 2000-02, and the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-09. In each case, China’s high growth and massive issuance of stimulus and credit (a.k.a. China’s Credit Impulse) acted as catalysts to restart global expansion.

The context of this is China’s unprecedentedly rapid industrialization added a new (initially low-cost) very productive workforce of 450 million to the global economy, roughly equivalent to the entire workforces of the U.S. and the European Union. This was a one-off on multiple layers: an enormous workforce, ample reserves of cheap coal and aggressively mercantilist government policies fueled a boom unlike any other in history. (I first visited China in 2000, shortly before its entry into the World Trade organization, so the boom is not an academic abstraction for me; I was there, witnessing it on the ground.)

This boom generated enormous capital flows into China (a.k.a. FDI, foreign direct investment), soaring corporate profits as developed-nations’ corporations slashed production costs by offshoring industries to China, and spurred domestic consumption in China as a nation of 1.4 billion people who had been held back for decades rushed to replace hundreds of millions of bicycles with hundreds of millions of autos and old brick houses with millions of high-rise apartments.

This one-off is now spent. Even in 2000, there were signs of overproduction / demand saturation: TV production in China in 2000 had overwhelmed global and domestic demand: everyone in China already had a TV, so what to do with the millions of TVs still being churned out?

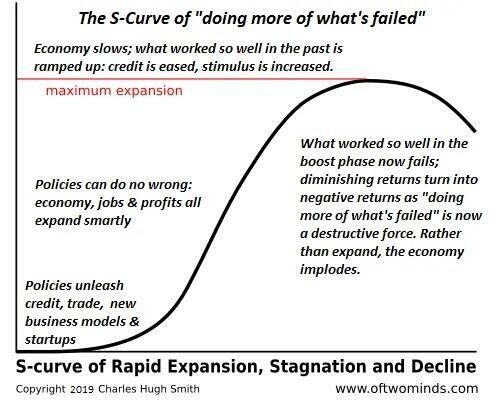

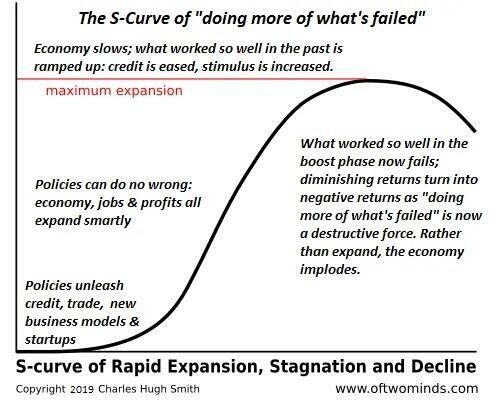

Daily life in China is high-tech, orderly, busy and prosperous–what visiting Westerners see and praise–but the narrative of China’s ascent to global dominance via endless expansion of its economy has been punctured, again for a very simple reason: China’s model of economic development that worked so brilliantly in the “boost phase” of the S-Curve, when all the low-hanging fruit could be so easily picked, no longer works at the top of the S-Curve.

China’s model of economic development from 1985 to the present was classic mercantilism–government policies encouraged industrialization to ship low-cost exports to the world–and classic expansion of home ownership: though the state owns all land in China, government policy shifted from public housing to issuing long-term leases to residents and to developers to build new housing that would be sold to households.

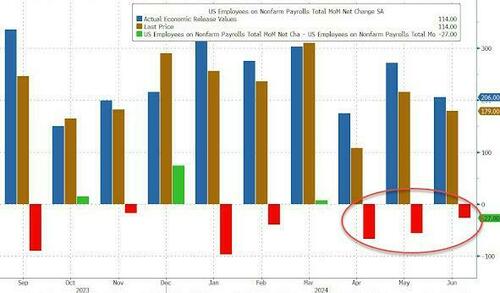

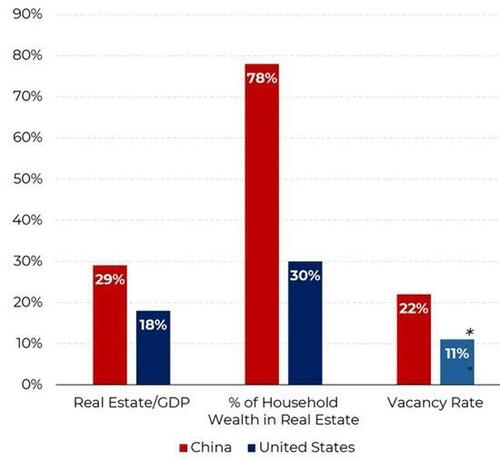

These policies have now reached the saturation-decline phase of the S-Curve, on multiple levels. Housing is now in surplus–millions of middle-class households already own investment apartments as a form of savings / household wealth–and half the populace is too poor to buy expensive flats: 600 million people get by on $150 or less per month.

These policies have led to an extreme concentration of household wealth in real estate, and those who invested in China’s stock market have suffered major losses.

There is little demand for existing flats outside the inner rings of Tier One cities, and so the resale value of millions of empty investment flats is a looming question mark. Small banks have folded or are limiting cash withdrawals, sparking protests, and an estimated 20 million flats that homeowners have paid for are unfinished as the developers ran out of money.

This is the problem with overproduction as a model of endless growth: it eventually overwhelms demand and the income needed to pay for it.

On the export front, China’s heavy-handed policies (Wolf Warrior diplomacy) have alienated both the developing-nations who took on huge loans from China for Belt-and-Road Initiative projects–many of which are empty white elephants or plagued with quality issues–and the developed-world economies facing a tsunami of Chinese exports that are now viewed as mortal threats to domestic industries and national security.

Simply put, housing and mercantilist exports are no longer engines of growth, and China has no replacement. The current strategy of moving up the value chain to dominate electric vehicles and semiconductors is triggering pushback in the form of tariffs and restrictions that will only increase as the global economy slips into recession.

Whatever reflects poorly on the leadership is suppressed–statistics are simply no longer reported or are dismissed as PR–and so it takes on-the-ground reporting to learn that youth unemployment is likely around 40%, civil servants such as police have had their salaries cut 30%, and that the citizenry now view the present as “the Garbage Time of History.”: Deals like the “Poor Guy’s Package” and “Blind Box of Leftovers” point to significant changes in the Chinese economy affecting the lives of ordinary people.

China’s credit stimulus–breathlessly anticipated as the savior of the global economy–generated nothing more than a shrug. China has burned through the boost phase and has no answers to the decay phase of the S-Curve.

Constructive demographics were another one-off–for China and for the world.

Where China’s workforce was growing during the boost phase, now the demographic picture has darkened: China’s workforce is shrinking, the population of elderly retirees is soaring, and China has no national universal pension / healthcare programs like Social Security and Medicare, so the cost burdens of supporting a burgeoning cohort of retirees will have to be funded by a shrinking workforce.

This is a global phenomenon, and there are no quick and easy solutions. Skilled labor will become increasingly scarce and able to demand higher wages regardless of any other factors, and that will be a long-term source of inflation. Governments will have to borrow more–and probably raise taxes as well–to fund soaring pension and healthcare costs for elderly retirees. This will bleed off other social spending and investment.

The era of zero-interest rates and unlimited government borrowing has ended. As Japan has shown, even at ludicrously low rates of 1%, interest payments on skyrocketing government debt eventually consume virtually all tax revenues. Higher rates will accelerate this dynamic, pushing government finances to the wall as interest on sovereign debt crowds out all other spending. As taxes rise, households have less disposable income to spend on consumption, leading to stagnation.

At the start of the cycle–either 1985 or 1994, take your pick–global debt levels, both government and private-sector–were low. Now they are high. The boost phase of debt expansion and debt-funded spending is over, and we’re in the stagnation-decline phase where adding debt generates diminishing or negative returns.

The era of low inflation has also ended for multiple reasons. Exporting nations’ wages have risen sharply, pushing their costs higher, and as noted, skilled labor in developed economies can demand higher wages as this labor cannot be automated or offshored–and offshoring is reversing to onshoring, raising production costs and diverting investment from asset bubbles to the real world.

The techno-optimist fantasy is that technology will extract all the minerals and resources we need to completely remake the global energy sector and every device that consumes energy at current low prices. This has yet to proven correct at scale, and common sense suggests it will be proven false as we’ve already consumed all the easy-to-extract resources in locales that aren’t extreme. OK, so there’s oil under the Arctic Sea. Nice, but it won’t be cheap and easy to get like the oil that’s already been extracted and consumed.

Higher costs of extraction will push inflation higher. So will rampant money-printing to “boost consumption.”

The tech boom was also a one-off. Economists were puzzled in the early 1990s by the stagnation of productivity despite the tremendous investments made in personal and corporate computers, a boom launched in the mid-1980s with Apple’s Macintosh and desktop publishing, and Microsoft’s WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get) Windows operating system.

By the mid-1990s, productivity was finally rising and the emergence of the Internet as “the vital 4%” triggered the adoption of the 20% which then led to 80% getting online combined with the computing revolution to generate a true revolution in sharing, connectivity and economic potential.

The buzz around AI holds that an equivalent boom is now starting that will generate a glorious “Roaring 20s” of trillions booked in new profits and skyrocketing productivity as white-collar work and jobs are automated into oblivion.

There are two problems with this story:

1) The projections are based more on wishful thinking than real-world dynamics

2) If the projections come true and tens of millions of white-collar jobs disappear forever, there is no replacement sector to employ the tens of millions of unemployed workers.

In the previous cycles of industrialization and post-industrialization, agricultural workers shifted to factory work, and then factory workers shifted to retail, services and office work. There is no equivalent place to shift tens of millions of unemployed workers, as AI is a dragon that eats its own tail: AI can perform many programming tasks so it won’t need millions of human coders.

As for profits, as I explained in Musings #1 (AI Boosts Productivity: Hype, Reality or Mirage?), Musings #26 (The Simple Reason Nothing Is Fixable: Addiction Capitalism) and #27 (Will Hollywood and the Music Industry Survive the Super-Abundance of Original AI Content?), everyone will have the same AI tools and so whatever those tools generate will be overproduced and therefore of little value: there is no pricing power when the world is awash in AI-generated content, bots, etc., other than the pricing power offered by addiction and fraud–both extreme negatives for humanity and the global economy.

Either way it goes–AI is a money-pit of grandiose expectations that will generate marginal returns, or it wipes out much of the middle class while generating little profit–AI will not be the miraculous source of millions of new high-paying jobs and astounding profits.

To recap: here are the one-offs that drove growth and pulled the global economy out of bubble busts / recessions for the past 30 years:

1) China’s industrialization.

2) Growth-positive demographics.

3) Low interest rates.

4) Low debt levels.

5) Low inflation.

6) Tech boom.

These one-offs no longer exist. They’re gone or have reversed. What we now have is a hyper-centralized, hyper-connected (i.e. tightly bound), hyper-globalized and hyper-financialized global economy of extreme fragility.

For all these reasons, the usual stimulus tricks won’t work this time around.