Authored by Robert Huebscher of Advisor Perspectives, who shares his perspectives from SocGen’s latest Global Strategy Presentation, hosted by the bank’s legendarily pessimistic strategist, Albert Edwards and SocGen’s (no less bearish) market quant Andrew Lapthorne. It is also known as the “Woodstock for Bears.”

Expect a recession in the next 18 months, said Albert Edwards. Bond yields will converge with those in Germany and will go negative. The economy will be in deflation – or at least face a significant deflationary “scare.” Those factors, he said, will create a terrific opportunity for fixed-income investors.

Edwards is the global strategist for Société Générale and is based in London. He spoke at his firm’s annual investment conference in London on January 15. Also speaking were Andrew Lapthorne, who runs quantitative analysis for the firm, and Gerard Minack, an Australian-based global strategist.

In addition to his forecast for the U.S. economy and markets, Edwards said two countries are poised to deliver destabilizing shocks to global growth: Italy and Japan.

The ice age and the threat of a recession

Edwards is known for his “ice age” thesis, which posited that, beginning in 1996, the correlation between bond and stock yields would break down, and 10-year bonds would outperform stocks. His template was Japan and its lost decade of growth, which began in 1990. While his forecast has been largely accurate, he noted that it has been disrupted by quantitative easing (QE) since 2011. Now, with the Fed, ECB and Bank of Japan all tightening, he expects the ice age to continue.

But Edwards cautioned against underestimating the effect of central-bank tightening. Recessions are more likely to be caused by events in the markets – not the other way around, he said, as is commonly assumed.

The economist Brad de Long has noted that three of last four recessions were from unforeseen shocks in financial markets (the collapse of the dot-com bubble, the real estate bubble and the S&L crisis). The exception was the 1979-1982 recession. Edwards pointed out that the very minor episode of quantitative easing (QT) that started in October 2018 caused a very rapid unwinding of equity valuations – illustrating the outsized effect such actions can have on markets.

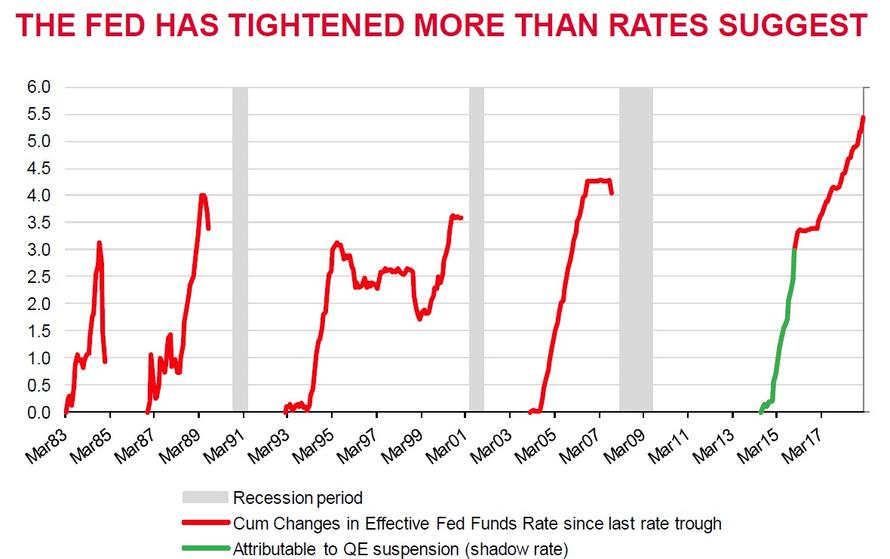

“We underestimate the amount of QT,” he said. He cited an academic study that shows that QE effectively pushed the Fed funds rate to -3.0%. The effect of QT has been to push the rate to effectively 5.5%, according to Edwards.

Edwards noted that the fiscal policy deficit has gone to 4% of GDP. He said that it is not the level, but rather the change in the deficit, that matters. In the U.S., there was a 1% discretionary expansion in fiscal policy last year, but this is now reversing. In Q4 of last year, he said the change in the deficit went form 0.5% of stimulus to 0.5% of tightening in Q1 – “a massive foot on the brake.”

“The U.S. will follow everyone else with a very rapid economic slowdown,” Edwards said.

The economist Larry Summers has asked rhetorically, with 3% growth last year, “How could there be a recession?” Edwards answered by pointing out that 75% of recessions have had 3% or greater growth in the previous year.

The IMF is predicting “barely a slowdown at all,” he said, “but commodities – particularly base metals – are telling us it could be a lot more severe.” Edwards added that metrics such as CEO confidence and the manufacturing ISM are poor, and that the ECRI also suggests a very sharp slowdown.

Ten of the last 13 Fed tightening cycles have ended in recession, Edwards said. Ahead of a downturn, as the Fed tightens, the yield curve steepens. “That is the phase we are in now,” he said. “Just because the jobs market is buoyant, as it was preceding the last two recessions, doesn’t mean there won’t be a recession.” Typically payrolls accelerate ahead of recessions, he said. “Strong payrolls don’t necessarily mean a recession is not coming.”

In terms of the bond market, there was a lot of panic when the 10-year broke out of the upper bound of its long-term downtrend, he said. There were extreme speculative shorts, he said, which led him to believe yields could snap back sharply. The same happened in June 2006, and six months later the economy was in deep recession.

“Little did we think that Fed Chair Powell would encourage the whip-around in interest rates that we’ve seen,” he said. Other Fed speakers have since echoed the dovish posture, helping prop up equity valuations.

His key prediction was that over the next 12- to 18-month period, U.S. bonds yields will decline and converge with those in Germany and Switzerland. Those yields will end up in negative territory, according to Edwards.

Italy

Don’t accept the explanation that the weak data in Europe is due to a tightening of emission standards, Edwards said. There is a deeper, structural problem.

The core of that problem is weak productivity and Italy is “in a league of its own” on that basis, he said. One possible explanation is that Italy suffers from poor student performance in its schools, and that has led to high unemployment. Edwards cited survey data which showed that, among all Eurozone countries, Italy was the only one where unemployment was cited as one of the top two concerns of its citizens.

“But the real problem is Italy is locked in the Eurozone,” Edwards said. Every single year its effective exchange rate goes up because its labor costs are rising. That happened in the last decade, he said, and France is not far behind Italy.

“The Eurozone will split up,” he said adding that the core problem in Italy is youth unemployment, now at 32%, which he said was astounding given the ECB’s QE.

Italy is unique, he said, in that a majority of those under 45 years old want to leave the EU. That is the opposite of public opinion in the UK, Germany, France and Holland. Italy is swinging towards leaving the EU, he said, even before next recession when unemployment “will go above 50%”, he predicted.

China

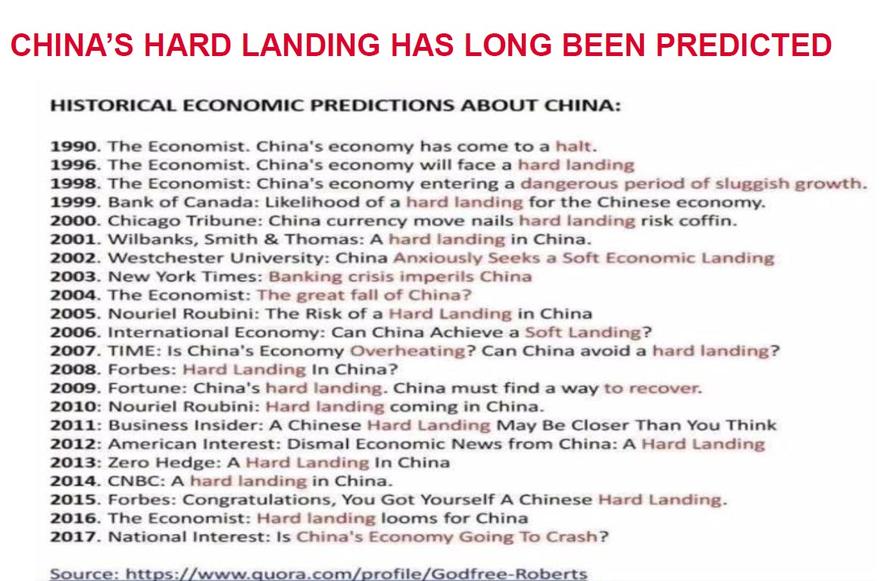

Every year since 1990, people have been calling for a Chinese “hard landing,” Edwards said. “Now they are calling for an adjustment from an investment to a consumption bias in China’s economy.”

It is going slowly, he said, and China is still hugely reliant on consumption, especially compared to other emerging markets at this stage of their development.

Policymakers are not going to open the floodgates to credit in response to the slowdown, according to Edwards. One can see this in the data, which shows that reserves have leveled off, he said, so China is actually engaging in monetary tightening. This is “grinding away in the background,” he said.

Most of the economic data is very, very weak. Industrial profits are at the lowest level in two years, down 20% year-over-year.

“The current unraveling in China is much harder than people suppose,” Edwards said.

The PMI data shows that export orders slumped sharply in the last three months, and there is “a lot more weakness to come.”

Unemployment is the problem in China, he said. “Everything else is peripheral. This is where the social unrest comes from.” The slide below illustrates this problem.

Edwards cited a little-known data source, the Chinese “beige book,” which has been around since 2010. It surveys thousands of companies. A key conclusion from it is that “risk is going up as plentiful borrowing is failing to produce growth”, he said.

The risk is that China overtightens and loses control, according to Edwards. “There is far too much confidence in policymakers’ ability to control everything.”

The full presentation used by Edwards and Lapthorne is below

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2CErTXA Tyler Durden