The amount of mental acrobatics that Wall Street analysts have to perform to justify continued buying of stocks even as bonds scream deflation, the yield curve screams contraction, Europe and China are already one foot in a recession, and earnings are set for their first profit contraction in 3 years, is simply staggering.

One week ago, we reported that in keeping with its now traditional “good quant, bad quant” strategy (profiled most recently here), just hours later, JPMorgan’s “other” quant, Nikolaos Panigirtzoglou published a report in which he said that while he maintains a risk-on and pro-cyclical stance (the alternative is risking being dubbed “fake news” by Kolanovic), he warned that “investors should start building up hedges against the risk of a repeat of the past two weeks’ yield curve inversion episode.”

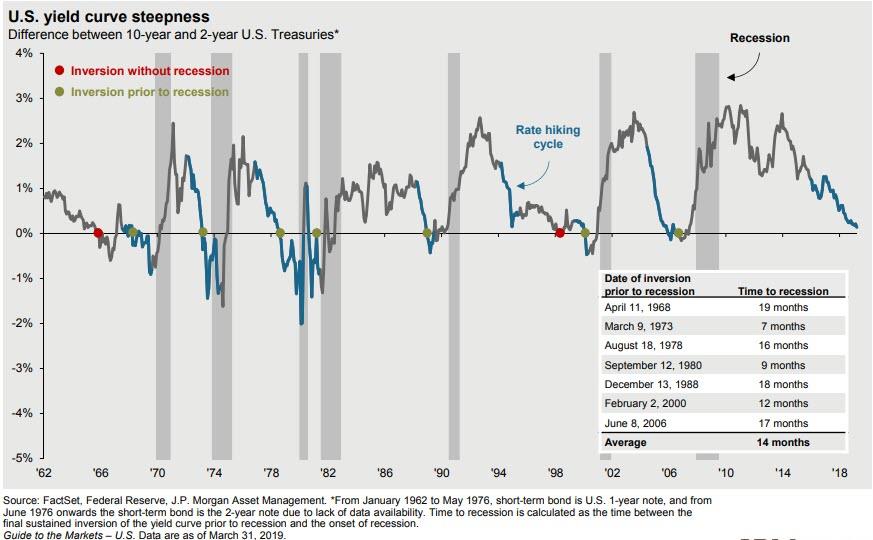

Picking up on what he said two weeks ago, the JPMorgan strategist noted that “yield curve inversion has been generally a bad omen for growth and recession risk, though with variable lags to risky asset prices historically.” And while not news to those who read our latest recap of Panigirtzoglou recent report, at the macro level the “other” JPM quant warns that “despite the improvement in the Chinese and Asian PMIs in this week’s releases the global growth picture is not out of the woods yet” adding that “these cyclical risks are still manifesting in our global manufacturing PMI, which has failed to rise in the latest release despite better Asian PMIs”.

Then over the weekend, in order to dispel fears that stocks have levitated too high, one strategist came out with a “novel” interpretation, claiming that there is no reason to worry as, drumroll, equity investors have been worried about the wrong yield curve. That strategist: Mislav Matejka who works for JPMorgan, and is a co-worker of the far more skeptical Panigirtzoglou.

That’s right, one bank, two diametrically opposing takes on what the yield curve means for investors.

According to the “other” JPM strategist, while there’s concern that the recent inversion of the yield curve is a sell signal for the market, he notes there’s an average 18-month lag between such a move and the onset of a recession, Matejka said in a note to investors Monday.

His solution? Ignore the “bad omen” for stocks highlighted by JPMorgan’s Panigirtzoglou, and inatead please just look at the spread between the 10-year and 2-year Treasury yields – which is about 18 basis points away from inversion – instead of using the inverted 10-year and 3-month Treasury yield difference that has stock traders – and his own JPMorgan co-worker – on edge.

But while disagreements between different strategists at the same bank is hardly new, what is remarkable is what a third – and even more bullish – JPMorgan strategist told Barron’s to further stoke the bullish narrative.

In order to justify JPMorgan’s 3,000 price target in the S&P, in an interview with Barron‘s, the bank’s chief U.S. equity strategist Dubravko Lakos-Bujas said that while many strategists and investors try to predict the end of the business current cycle, he boldly claimed that it may be time to reconsider its very existence.

That’s right: with the US poised to enter its longest expansion on record in June (absent a recession in the next month or so, which looks unlikely except in retrospect) and with rising concerns that the economy is now extremely “late cycle”, JPMorgan’s solution is to ignore the business cycle entirely, as central banks have now effectively taken over micromanaging the global economy.

“We are all used to using the word ‘cycle’; we’re all used to looking at historical charts and graphs and equations and relationships,” Lakos-Bujas told Barron’s. “The reality is that maybe the word ‘cycle’ is no longer even relevant, given that we have so much unconventional central-bank involvement.”

Why does the JPM chief equity strategist feel comfortable with making such a ludicrous statement? It has everything to do with the lack of inflation (because on Wall Street, as well as in the Federal Reserve HQ, there is no such thing as surging housing, healthcare, education and food prices and all the focus is on deflating, and edible, iPads).

“The fact that we’re not seeing really significant inflation pressure—it remains positive but tame—suggests that there’s no reason for central-bank policy to rush,” he said, pitching central planning with the passion and fervor of a Communist Party undersecretary speaking in front of Leonid Brezhnev in 1968 Moscow.

Of course, as Barron’s noted, central banks have done more than just keep rates low: central banks have put their balance sheets to work like never before, with large-scale asset purchases injecting liquidity into economies around the world. The ECB has gone even further than the Fed, buying up both sovereign and corporate bonds. The Bank of Japan took it to yet another level, purchasing equities in addition to bonds; its balance sheet is now above 100% of Japan’s GDP.

“This is not a normal cycle just left to itself to run. It is continually fiddled with by these central-bank injections,” he says, as if that were a good thing. And apparently it is, because the positive spin on the entire world becoming a 1960s version of the USSR is that “rather than nearing the end of one decadelong cycle, perhaps it’s just the beginning of a fourth mini-cycle.”

The first cycle he identifies ran from 2009 to 2012, when the European debt crisis forced the ECB to be creative in its measures to support debt-burdened euro-zone economies. The next phase lasted until 2016, when some emerging markets slipped into recession and U.S. corporate profits declined for two quarters. It ended when the Fed paused interest-rate increases and other central banks turned more accommodative. Another mini-cycle ended in the fourth quarter of 2018, when the Fed pivoted to a dovish stance and China began fiscal stimulus.

That brings us to the start of 2019, when a fourth cycle might have begun. “We have these little mini-cycles that are continuously occurring, and they seem to coincide with central-bank policy,” Lakos-Bujas says.

Unlike his more bearish JPM colleague, Panagirtzoglou who has been skeptical for the better part of the past 4 months, Lakos-Bujas – just like Marko Kolanovic – sees the S&P 500 going to 3000 this year, as investors steadily become willing to take on more risk and overhangs like the U.S.-China trade dispute are resolved.

Perhaps there is something about Croatian genes predisposing analysts (Kolanovic, Matejka, Lakos-Bujas) to be especially bullish: we don’t know and it doesn’t really matter. But what struck us, is the lack of any critical observation or rational analysis of the dangers of central banks constantly stepping in to push stocks higher at any downside inflection points, something Bank of America pointed out over a year ago.

After all, in a world in which the economy is increasingly the market (where easy central banks and record buybacks are all that matter), all that is happening is that this increasingly artificial “market” is creating a world with record “zombie companies”, and staggering economic imbalances whose day of reckoning is not being resolved but merely delayed, guaranteeing that when the market finally does crack, not only will what little central bank credibility is left be crushed, but the world will fall into a depression the likes of which will make the 1920s and 1930s seems like a walk in the park.

via ZeroHedge News http://bit.ly/2Ki7zm8 Tyler Durden