Julian Assange is exactly the kind of person that prompts bad policy to be made. A polarizing figure with the wrong politics for America’s media establishment and a history of lurid allegations against him, Assange’s fate is easy for many to dismiss as what the WikiLeaks founder deserves.

When Assange, who had been living in the Ecuadorian embassy in London, was arrested by British police Thursday, “few, if any, politicians defended Assange or suggested that it might be wrong to prosecute him,” Joe Setyon pointed out yesterday. Even libertarian-leaning folks like Sen. Rand Paul (R–Ky.) and Rep. Justin Amash (R–Mich.) have thus far been mum.

Rep. Tulsi Gabbard (D–Hawaii) is pretty much the only elected politician to stick up for Assange’s rights. She told CNN yesterday that Assange had successfully “informed the American people about actions that were taking place that they should be aware of” and that his prosecution by U.S. law enforcement is “some form of retaliation.”

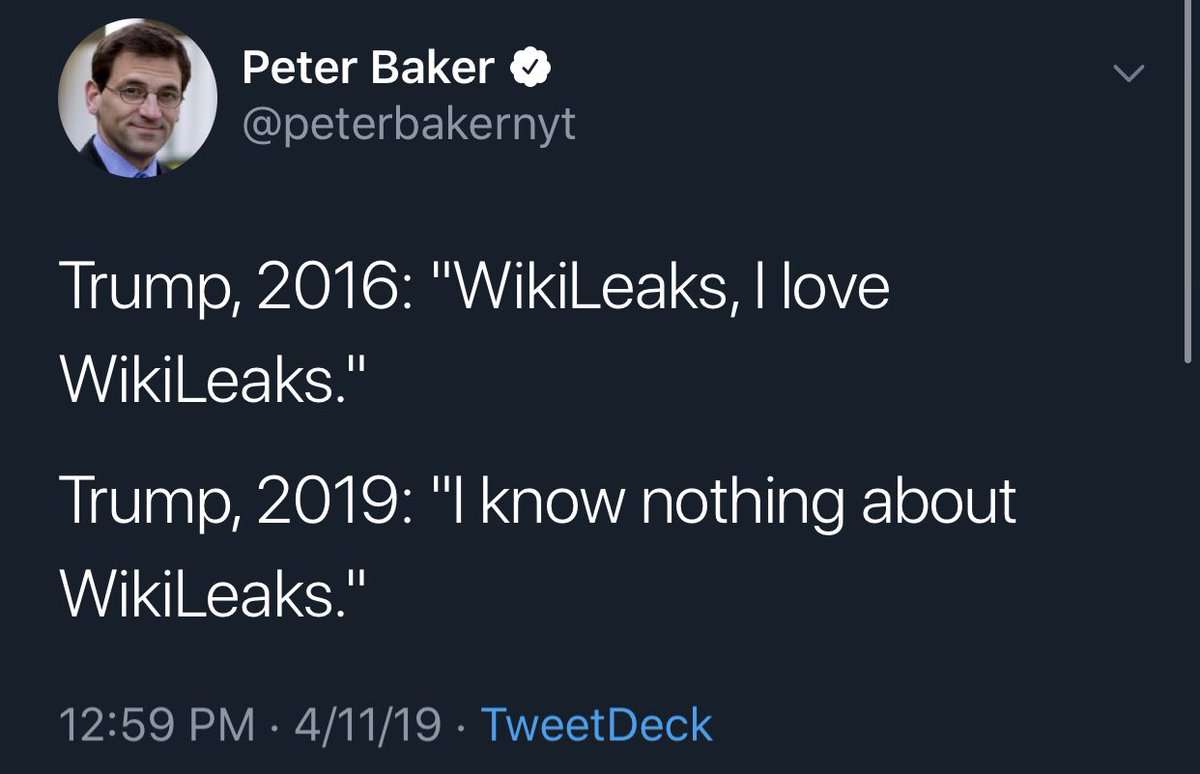

For President Donald Trump’s part, he simply claimed not to know anything about WikiLeaks at all, despite heaping praise on it in the past.

Let’s put aside Assange for a moment—because when laws are written or precedents set based only on whether Bad People are bad, we all lose. We let powerful figures convince us that giving that Bad Person what they deserve is what matters most, consequences be damned. And then we end up creating all sorts of new injustices to “correct” for a perceived past one.

What the government and its cheerleaders are really asking here is for us to suspend fundamental principles and practices underlying free speech and a free press.

It is not uncommon for confidential sources in government, business, and other powerful institutions to leak information to journalists and publishers. This is how we’ve found out about some of the biggest political scandals of the past 100 years. But now the U.S. Department of Justice is suggesting that these basic news-gathering and reporting functions are criminal.

And officials are relying on hurt feelings about Russia to distract people from what’s really going on.

The American charges that Assange faces relate to WikiLeaks’ publication of documents on the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, using files leaked by Chelsea Manning. The feds also accuse Assange of “conspiring” with Manning to uncover more classified information along these lines. The case does not have anything to do with any alleged Assange ties to Russia, or WikiLeaks’ publication of the Democratic National Committee’s emails, or the 2016 election at all.

“The Assange indictment is weaker than you might expect,” tweeted the constitutional lawyer and former federal prosecutor Ken “Popehat” White yesterday. “It charges that Assange and Manning conspired to access government computers (to hack, in the vernacular). BUT it doesn’t say they succeeded.”

At The Washington Post, Margaret Sullivan suggests that the situation hinges on whether Assange crossed “a crucial line by allegedly encouraging the password hack” instead of just passively receiving the information. I don’t think that’s quite such a clear demarcation. Suppose a source says she has information on huge government abuses and could get proof of more if she can guess one password. Should simply saying “Sure, go for it” count as a crime? How could it be that this is beyond the pale but otherwise encouraging a source to turn over classified information is not?

First Amendment lawyer Barry Pollack tells Sullivan that the indictment against Assange was narrow and didn’t criminalize the mere receiving and publishing of classified information. But the line there is a little too close for comfort for me, and many others.

“Reminder, *everything a reporter does* to facilitate a source anonymously sending that reporter classified info is ‘helping them commit a crime,’” tweets Cato policy analyst Julian Sanchez. “That’s not a useful way to talk about what distinguishes the Assange case.”

The indictment may not directly call certain journalist practices criminal, but it does include them—things like using encrypted communications and attempting to protect a source’s identity—as among the elements that suggest Assange is guilty of conspiracy

The indictment “poses grave threats to press freedoms, not only in the U.S. but around the world,” write Glenn Greenwald and Micah Lee at The Intercept:

The first crucial fact about the indictment is that its key allegation—that Assange did not merely receive classified documents from Chelsea Manning but tried to help her crack a password in order to cover her tracks—is not new. It was long known by the Obama DOJ and was explicitly part of Manning’s trial, yet the Obama DOJ—not exactly renowned for being stalwart guardians of press freedoms—concluded it could not and should not prosecute Assange because indicting him would pose serious threats to press freedom. In sum, today’s indictment contains no new evidence or facts about Assange’s actions; all of it has been known for years.

The other key fact being widely misreported is that the indictment accuses Assange of trying to help Manning obtain access to document databases to which she had no valid access: i.e., hacking rather than journalism. But the indictment alleges no such thing. Rather, it simply accuses Assange of trying to help Manning log into the Defense Department’s computers using a different user name so that she could maintain her anonymity while downloading documents in the public interest and then furnish them to WikiLeaks to publish.

The Assange prosecution “would be unprecedented and unconstitutional and would open the door to criminal investigations of other news organizations,” the ACLU’s Ben Wizner tells Sullivan.

The cocksure “Julian Assange wasn’t a journalist” takes make me incredibly uncomfortable.

Please read up on the Cincinnati Enquirer’s Chiquita Phone Hacking Scandal If you think the lines between “journalism” and “not-journalism” are so damn clear. https://t.co/LJyty3UEQf

— Dan Lavoie (@djlavoie) April 12, 2019

QUICK HITS

Virginia town refused to give man a license to open a Tarot shop. He got a permit to open a bookshop, and did Tarot readings for free. Christians were like !, town said it was illegal & refused to allow it under zoning ordinances.

(!)

ACLU is suing. https://t.co/pP1atxmVX3 pic.twitter.com/GKtNg5B4vp

— Peter Bonilla (@pebonilla) April 11, 2019

- Former FBI Director James Comey says he “never thought of” electronic surveillance as “spying.”

- Sen. Bernie Sanders (I–Vt.) speaks out against disenfranchising felons and people in prison. Sen. Kamala Harris says (like she does on just about everything thrown her way) that she was “open” to the idea. Indiana’s Pete Buttigieg said he supports restoring voting rights for felons once released from prison but not while they are incarcerated.

- “Helping,” government style:

Efforts to “rescue” sex workers in Swansea Wales will now include tough enforcement action and prosecution for sex workers who refuse support. https://t.co/BgtEvPql1U

— FIRST Decrim.SexWork (@FirstAdvocates) April 10, 2019

- More attempts to erode press freedom in the U.S.:

What the hell, Georgia? “the Ethics in Journalism Act… would authorize a board to create new ethical standards that govern journalists’ work, and to sanction journalists who violate them.” https://t.co/tdxEVVze5i Did you see this @reason crew?

— Ari Armstrong (@ariarmstrong) April 11, 2019

- Sex-trafficking survivors “should not have to ‘prove rehabilitation’ to access remedies that let them clear charges from their records,” argues Decrim NY.

- Alabama is at it again:

The Alabama Human Life Protection Act would be a disaster for women’s rights. In outlawing abortion it would set back women’s freedom by decades. It’s time for pro-choice activists to fight back, says @Ella_M_Whelanhttps://t.co/DeOIttQa6y

— spiked (@spikedonline) April 12, 2019

from Latest – Reason.com http://bit.ly/2Xb1cT0

via IFTTT